An identity document is a document proving a person's identity.

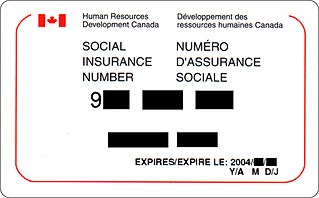

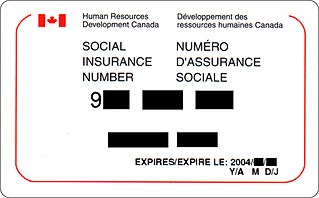

A social insurance number (SIN) (French: numéro d'assurance sociale (NAS)) is a number issued in Canada to administer various government programs. The SIN was created in 1964 to serve as a client account number in the administration of the Canada Pension Plan and Canada's varied employment insurance programs. In 1967, Revenue Canada (now the Canada Revenue Agency) started using the SIN for tax reporting purposes. SINs are issued by Employment and Social Development Canada (previously Human Resources Development Canada).

Taspo (タスポ), formerly known as Tobacco Card, is a smart card using RFID developed by the Tobacco Institute of Japan (TIOJ), the Nationwide Association of Tobacco Retailers, and the Japan Vending Machine Manufacturers Association for introduction in 2008. Following its introduction, the card is necessary in order to purchase cigarettes from vending machines in Japan. The name "Taspo" is a portmanteau for "tobacco passport".

A national identification number, national identity number, or national insurance number or JMBG/EMBG is used by the governments of many countries as a means of tracking their citizens, permanent residents, and temporary residents for the purposes of work, taxation, government benefits, health care, and other governmentally-related functions.

The Malaysian identity card is the compulsory identity card for Malaysian citizens aged 12 and above. The current identity card, known as MyKad, was introduced by the National Registration Department of Malaysia on 5 September 2001 as one of four MSC Malaysia flagship applications and a replacement for the High Quality Identity Card, Malaysia became the first country in the world to use an identification card that incorporates both photo identification and fingerprint biometric data on an in-built computer chip embedded in a piece of plastic. The main purpose of the card as a validation tool and proof of citizenship other than the birth certificate, MyKad may also serve as a valid driver's license, an ATM card, an electronic purse, and a public key, among other applications, as part of the Malaysian Government Multipurpose Card (GMPC) initiative, if the bearer chooses to activate the functions.

In the United States, identity documents are typically the regional state-issued driver's license or identity card, while also the Social Security card and the United States passport card may serve as national identification. The United States passport itself also may serve as identification. There is, however, no official "national identity card" in the United States, in the sense that there is no federal agency with nationwide jurisdiction that directly issues an identity document to all US citizens for mandatory regular use.

A Belgian identity card is a national identity card issued to all citizens of Belgium aged 12 years old and above.

The National Registration Identity Card (NRIC), colloquially known as "IC", is a compulsory identity document issued to citizens and permanent residents of Singapore. People must register for an NRIC within one year of attaining the age of 15, or upon becoming a citizen or permanent resident. Re-registrations are required for persons attaining the ages of 30 and 55, unless the person has been issued with an NRIC within ten years prior to the re-registration ages.

The CPF number is the Brazilian individual taxpayer registry, since its creation in 1965. This number is attributed by the Brazilian Federal Revenue to Brazilians and resident aliens who, directly or indirectly, pay taxes in Brazil. It's an 11-digit number in the format 000.000.000-00, where the last 2 numbers are check digits, generated through an arithmetic operation on the first nine digits.

The Romanian identity card is an official identity document issued to every Romanian citizen residing in Romania. It is compulsory to obtain the identity card from 14 years of age. Although Romanian citizens residing abroad are exempt from obtaining the identity card, if they intend to establish a temporary residence in Romania, they may then apply for a provisional identity document, which is valid for one year (renewable).

The Estonian identity card is a mandatory identity document for citizens of Estonia. In addition to regular identification of a person, an ID-card can also be used for establishing one's identity in electronic environment and for giving one's digital signature. Within Europe as well as French overseas territories, Georgia and Tunisia the Estonian ID-card can be used by the citizens of Estonia as a travel document.

Alien registration was a system used to record information regarding aliens resident in Japan. It was handled at the municipal level, parallel to the koseki and juminhyo systems used to record information regarding Japanese nationals.

The Basic Resident Registers Network or Juki Net is a national registry of Japanese citizens. It was ruled constitutional by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 6, 2008 amidst strong opposition.

A resident register is a government database which contains information on the current residence of persons. In countries where registration of residence is compulsory, the current place of residence must be reported to the registration office or the police within a few days after establishing a new residence. In some countries, residence information may be obtained indirectly from voter registers or registers of driver licenses. Besides a formal resident registers or population registers, residence information needs to be disclosed in many situations, such as voter registration, passport application, and updated in relation to drivers licenses, motor vehicle registration, and many other purposes. The permanent place of residence is a common criterion for taxation including the assessment of a person's income tax.

In the United States, a Social Security number (SSN) is a nine-digit number issued to U.S. citizens, permanent residents, and temporary (working) residents under section 205(c)(2) of the Social Security Act, codified as 42 U.S.C. § 405(c)(2). The number is issued to an individual by the Social Security Administration, an independent agency of the United States government. Although the original purpose for the number was for the Social Security Administration to track individuals, the Social Security number has become a de facto national identification number for taxation and other purposes.

The Nationality law of Myanmar currently recognises three categories of citizens, namely citizen, associate citizen and naturalised citizen, according to the 1982 Citizenship Law. Citizens, as defined by the 1947 Constitution, are persons who belong to an "indigenous race", have a grandparent from an "indigenous race", are children of citizens, or lived in British Burma prior to 1942.

The Computerised National Identity Card (CNIC) is an identity card with a 13-digit number available to all adult citizens of Pakistan and their diaspora counterparts, obtained voluntarily. It includes biometric data such as 10 fingerprints, 2 iris prints, and a facial photo. The National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA), was established in 1998 as an attached department under the Ministry of Interior, Government of Pakistan. Since March 2000, NADRA has operated as an independent corporate body with the requisite autonomy to collect and maintain data independently.

Manaca, stylized in lowercase as manaca is a rechargeable contactless smart card used in Nagoya, Japan and the surrounding area in Aichi Prefecture. It launched on February 11, 2011, replacing the Tranpass magnetic fare card system. Since 2013, it has been part of Japan's Nationwide Mutual Usage Service, allowing it to be used in all major cities across the country.

The Resident Identity Card is an official identity document for personal identification in the People's Republic of China. According to the second chapter, tenth clause of the Resident Identity Card Law, residents are required to apply for resident identity cards from the local Public Security Bureau, sub-bureaus or local executive police stations.

An Individual Number, also known as My Number, is a twelve-digit ID number automatically issued to all citizens and residents of Japan used for taxation, social security and disaster response purposes. The numbers were first issued in late 2015.