Related Research Articles

The Liberal Party was one of the two major political parties in the United Kingdom with the opposing Conservative Party in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The party arose from an alliance of Whigs and free trade-supporting Peelites and the reformist Radicals in the 1850s. By the end of the 19th century, it had formed four governments under William Gladstone. Despite being divided over the issue of Irish Home Rule, the party returned to government in 1905 and then won a landslide victory in the following year's general election.

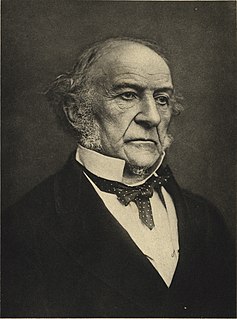

William Ewart Gladstone was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four terms beginning in 1868 and ending in 1894. He also served as Chancellor of the Exchequer four times, serving over 12 years.

Joseph Chamberlain was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then, after opposing home rule for Ireland, a Liberal Unionist, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Conservatives. He split both major British parties in the course of his career. He was father, by different marriages, of Austen Chamberlain and of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain.

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington and Joseph Chamberlain, the party formed a political alliance with the Conservative Party in opposition to Irish Home Rule. The two parties formed the ten-year-long coalition Unionist Government 1895–1905 but kept separate political funds and their own party organisations until a complete merger between the Liberal Unionist and the Conservative parties was agreed to in May 1912.

Charles Stewart Parnell was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party from 1882 to 1891. His party held the balance of power in the House of Commons during the Home Rule debates of 1885–1886.

John Poyntz Spencer, 5th Earl Spencer, KG, KP, PC, known as Viscount Althorp from 1845 to 1857, was a British Liberal Party politician under, and close friend of, British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone. He was twice Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, styled Lord Cavendish of Keighley between 1834 and 1858 and Marquess of Hartington between 1858 and 1891, was a British statesman. He has the distinction of having served as leader of three political parties: as Leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Commons (1875–1880), of the Liberal Unionist Party (1886–1903) and of the Unionists in the House of Lords (1902–1903). After 1886 he increasingly voted with the Conservatives. He declined to become prime minister on three occasions, because the circumstances were never right. Historian Roy Jenkins said he was "too easy-going and too little of a party man." He held some passions, but he rarely displayed them regarding the most controversial issues of the day.

The Irish Parliamentary Party was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nationalist Members of Parliament (MPs) elected to the House of Commons at Westminster within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland up until 1918. Its central objectives were legislative independence for Ireland and land reform. Its constitutional movement was instrumental in laying the groundwork for Irish self-government through three Irish Home Rule bills.

Sir William George Granville Venables Vernon Harcourt was a British lawyer, journalist and Liberal statesman. He served as Member of Parliament for Oxford, Derby then West Monmouthshire and held the offices of Home Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer under William Ewart Gladstone before becoming Leader of the Opposition. A talented speaker in parliament, he was sometimes regarded as aloof and possessing only an intellectual involvement in his causes. He failed to engender much emotional response in the public and became only a reluctant and disillusioned leader of his party.

John Morley, 1st Viscount Morley of Blackburn, was a British Liberal statesman, writer and newspaper editor.

The 1906 United Kingdom general election was held from 12 January to 8 February 1906.

The 1892 United Kingdom general election was held from 4 to 26 July 1892. It saw the Conservatives, led by Lord Salisbury again win the greatest number of seats, but no longer a majority as William Ewart Gladstone's Liberals won 80 more seats than in the 1886 general election. The Liberal Unionists who had previously supported the Conservative government saw their vote and seat numbers go down.

In the United Kingdom, the word liberalism can have any of several meanings. Scholars use the term to refer to classical liberalism; the term also can mean economic liberalism, social liberalism or political liberalism; it can simply refer to the politics of the Liberal Democrat party; it can occasionally have the imported American meaning, however, the derogatory connotation is much weaker in the UK than in the US, and social liberals from both the left and right wing continue to use liberal and illiberal to describe themselves and their opponents, respectively.

The third Gladstone ministry was one of the shortest-lived ministries in British history. It was led by William Ewart Gladstone of the Liberal Party upon his reappointment as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom by Queen Victoria. It lasted five months until July 1886.

Sir Wilfrid Lawson, 2nd Baronet was an English temperance campaigner and radical, anti-imperialist Liberal Party politician who sat in the House of Commons variously between 1859 and 1906. He was recognised as the leading humourist in the House of Commons.

Gladstonian liberalism is a political doctrine named after the British Victorian Prime Minister and leader of the Liberal Party, William Ewart Gladstone. Gladstonian liberalism consisted of limited government expenditure and low taxation whilst making sure government had balanced budgets and the classical liberal stress on self-help and freedom of choice. Gladstonian liberalism also emphasised free trade, little government intervention in the economy and equality of opportunity through institutional reform. It is referred to as laissez-faire or classical liberalism in the United Kingdom and is often compared to Thatcherism.

William Ewart Gladstone was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom on four separate occasions between 1868 and 1894. He was noted for his moralistic leadership and his emphasis on world peace, economical budgets, political reform and efforts to resolve the Irish Question. Gladstone saw himself as a national leader driven by a political and almost religious mission, which he tried to validate through elections and dramatic appeals to the public conscience. His approach sometimes divided the Liberal Party, which he dominated for three decades. Finally Gladstone split his party on the issue of Irish Home Rule, which he saw as mandated by the true public interest regardless of the political cost.

Francis Schnadhorst was a Birmingham draper and English Liberal Party politician. He briefly held elected office on Birmingham Council, and was offered the chance to stand for Parliament in winnable seats, but he found his true metier was in political organisation and administration both in his home town as secretary of the highly successful Birmingham Liberal Association from 1867 to 1884, and nationally as secretary of the newly formed National Liberal Federation from 1877 to 1893. He was famously described as "the spectacled, sallow, sombre" Birmingham draper who within a short period of time was to establish himself through the Birmingham Liberal caucus as one of the most brilliant organisers in the country.

The National Liberal Federation (1877–1936) was the union of all English and Welsh Liberal Associations. It held an annual conference which was regarded as being representative of the opinion of the party's rank and file and was broadly the equivalent of a present-day party conference.

The Liberal Imperialists were a faction within the British Liberal Party around 1900 regarding the policy toward the British Empire. They supported the Boer War which most Liberals opposed, and wanted the Empire ruled on a more benevolent basis. The most prominent members were R. B. Haldane, H. H. Asquith, Sir Edward Grey and Lord Rosebery.

References

- 1 2 "Newcastle Programme". A Dictionary of British History. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Chris Cook (2010). A Short History of the Liberal Party: The Road Back to Power. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 24–26. ISBN 9781137056078.

- ↑ Searle, G. R. (2001). The Liberal Party. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 33. ISBN 9780333786611.

- 1 2 3 Little, Tony (20 May 2012). "The Newcastle Programme". Liberal Democrat History Group . Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ↑ Robert Spence Watson (1907). The National Liberal Federation: From Its Commencement to the General Election of 1906. T. Fisher Unwin. p. 130.

- ↑ Bentley, Michael (1987). The Climax of Liberal Politics, 1868-1916: British Liberalism in Theory and Practice. Edward Arnold. p. 102. ISBN 9780713164947.

- ↑ Jenkins, Roy (1996). Gladstone. Papermac. p. 581. ISBN 9780333662090.

- ↑ Douglas, Roy (2005). Liberals: A History of the Liberal and Liberal Democrat Parties. Hambledon and London. p. 83. ISBN 9781852853532.

- ↑ Parry, Jonathan (1993). The Rise and Fall of Liberal Government in Victorian Britain. Yale University Press. p. 309. ISBN 9780300057799.

- ↑ Douglas 2005, p. 106.