Sino-Tibetan is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. Around 1.4 billion people speak a Sino-Tibetan language. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Sinitic languages. Other Sino-Tibetan languages with large numbers of speakers include Burmese and the Tibetic languages. Four United Nations member states have a Sino-Tibetan language as their main native language. Other languages of the family are spoken in the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif, and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Most of these have small speech communities in remote mountain areas, and as such are poorly documented.

The Mon language is an Austroasiatic language spoken by the Mon people. Mon, like the related Khmer language, but unlike most languages in mainland Southeast Asia, is not tonal. The Mon language is a recognised indigenous language in Myanmar as well as a recognised indigenous language of Thailand.

The Burmese alphabet is an abugida used for writing Burmese. It is ultimately adapted from a Brahmic script, either the Kadamba or Pallava alphabet of South India. The Burmese alphabet is also used for the liturgical languages of Pali and Sanskrit. In recent decades, other, related alphabets, such as Shan and modern Mon, have been restructured according to the standard of the Burmese alphabet

Burmese is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken in Myanmar, where it is the official language, lingua franca, and the native language of the Bamar, the country's principal ethnic group. Burmese is also spoken by the indigenous tribes in Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh, and in Tripura state in India. The Constitution of Myanmar officially refers to it as the Myanmar language in English, though most English speakers continue to refer to the language as Burmese, after Burma—a name with co-official status that had historically been predominantly used for the country. Burmese is the most widely-spoken language in the country, where it serves as the lingua franca. In 2007, it was spoken as a first language by 33 million. Burmese is spoken as a second language by another 10 million people, including ethnic minorities in Myanmar like the Mon and also by those in neighboring countries. In 2022, the Burmese-speaking population was 38.8 million.

Old Chinese, also called Archaic Chinese in older works, is the oldest attested stage of Chinese, and the ancestor of all modern varieties of Chinese. The earliest examples of Chinese are divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones from around 1250 BC, in the Late Shang period. Bronze inscriptions became plentiful during the following Zhou dynasty. The latter part of the Zhou period saw a flowering of literature, including classical works such as the Analects, the Mencius, and the Zuo Zhuan. These works served as models for Literary Chinese, which remained the written standard until the early twentieth century, thus preserving the vocabulary and grammar of late Old Chinese.

Yakkha is a language spoken in parts of Nepal, Darjeeling district and Sikkim. The Yakkha-speaking villages are located to the East of the Arun river, in the southern part of the Sankhuwasabha district and in the northern part of the Dhankuta district of Nepal. About 14,000 people still speak the language, out of 17,003 ethnic Yakkha in Nepal. Genealogically, Yakkha belongs to the Eastern Kiranti languages and is in one subgroup with several Limbu languages, e.g. Belhare, Athpare, Chintang and Chulung. Ethnically however, the Yakkha people perceive themselves as distinct from the other Kiranti groups such as Limbu.

Dulong or Drung, Derung, Rawang, or Trung, is a Sino-Tibetan language in China. Dulong is closely related to the Rawang language of Myanmar (Burma). Although almost all ethnic Derung people speak the language to some degree, most are multilingual, also speaking Burmese, Lisu, and Mandarin Chinese except for a few very elderly people.

Indosphere is a term coined by the linguist James Matisoff for areas of Indian linguistic influence in the neighboring Southern Asian, Southeast Asian, and East Asian regions. It is commonly used in areal linguistics in contrast with the Sinophone languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area of the Sinosphere. Notably, unlike terms such as Lusophone or Francophone that refer to the multinational spread and influence of a single language with multiple dialects, this term refers to all languages that are considered to originate in India, of which there are 22 recognised languages alone across several major language families, including Indo-European and Dravidian. It considers these collectively in regards to the influence of these languages on the languages of other countries, rather than from the perspective of the spread of the language only.

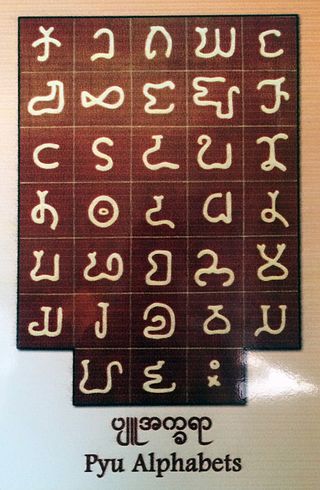

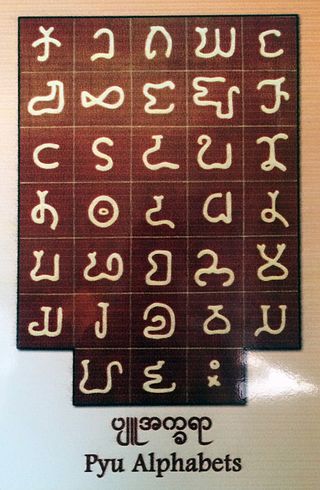

Myazedi inscription, inscribed in 1113, is the oldest surviving stone inscription of the Burmese language. "Myazedi" means "emerald stupa", and the name of the inscription comes from a pagoda located nearby. The inscriptions were made in four languages: Burmese, Pyu, Mon, and Pali, which all tell the story of Prince Yazakumar and King Kyansittha. The primary importance of the Myazedi inscription is that the inscriptions allowed for the deciphering of the written Pyu language.

The Pyu language is an extinct Sino-Tibetan language that was mainly spoken in what is now Myanmar in the first millennium CE. It was the vernacular of the Pyu city-states, which thrived between the second century BCE and the ninth century CE. Its usage declined starting in the late ninth century when the Bamar people of Nanzhao began to overtake the Pyu city-states. The language was still in use, at least in royal inscriptions of the Pagan Kingdom if not in popular vernacular, until the late twelfth century. It became extinct in the thirteenth century, completing the rise of the Burmese language, the language of the Pagan Kingdom, in Upper Burma, the former Pyu realm.

Burmese names lack the serial structure of most Western names. Like other Mainland Southeast Asian countries, the people of Myanmar have no customary matronymic or patronymic naming system and therefore have no surnames. Although other Mainland Southeast Asian countries introduced the using of surnames in early 20th century, Myanmar never introduced the using of surnames. So, Myanmar people don't have surnames. In the culture of Myanmar, people can change their name at will, often with no government oversight, to reflect a change in the course of their lives. Also, many Myanmar names use an honorific, given at some point in life, as an integral part of the name.

The phonology of Burmese is fairly typical of a Southeast Asian language, involving phonemic tone or register, a contrast between major and minor syllables, and strict limitations on consonant clusters.

Rudolf Alexeevich Yanson was a professor at St. Petersburg State University, where he was Chairman of the Department of Philology of China, Korea and Southeast Asia in the Faculty of Oriental Studies. He previously served as dean of the faculty of Oriental Studies. Yanson was on the board of the Moscow State Institute of Asian Studies. His research focused on the historical phonology of Burmese. In 2004 Yanson gave a welcoming address to a conference on Indonesian studies. Yanson served on the international advisory board of the SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research. He was scheduled to give the keynote address at the Fifth Medieval Tibeto-Burman Languages Symposium.

Proto-Tibeto-Burman is the reconstructed ancestor of the Tibeto-Burman languages, that is, the Sino-Tibetan languages, except for Chinese. An initial reconstruction was produced by Paul K. Benedict and since refined by James Matisoff. Several other researchers argue that the Tibeto-Burman languages sans Chinese do not constitute a monophyletic group within Sino-Tibetan, and therefore that Proto-Tibeto-Burman was the same language as Proto-Sino-Tibetan.

The Mon–Burmese script is an abugida that derives from the Pallava Grantha script of southern India and later of Southeast Asia. It is the basis of the alphabets used for modern Burmese, Mon, Shan, Rakhine, Jingpho and Karen.

Danau, also spelled Htanaw or Danaw, is an Austroasiatic language of Myanmar (Burma). It is the most divergent member of the Palaungic branch. According to community estimates (2023), Danau is spoken by about 3,000 people in six villages near Aungban, Kalaw Township, Shan State. Danau was described as a "critically endangered" language in UNESCO's 2010 Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.

Mruic or Mru–Hkongso is a small group of Sino-Tibetan languages consisting of two languages, Mru and Anu-Hkongso. Their relationship within Sino-Tibetan is unclear.

A History of the Pyu Alphabet is a book on the Pyu language first published in 1963 by Tha Myat.

The Mon alphabet is a Brahmic abugida used for writing the Mon language. It is an example of the Mon-Burmese script, which derives from the Pallava Grantha script of southern India.

Proto-Karenic or Proto-Karen is the reconstructed ancestor of the Karenic languages.