The uncertainty principle, also known as Heisenberg's indeterminacy principle, is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics. It states that there is a limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties, such as position and momentum, can be simultaneously known. In other words, the more accurately one property is measured, the less accurately the other property can be known.

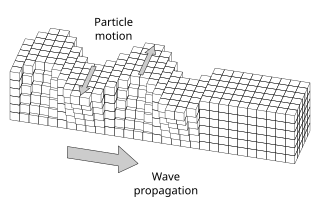

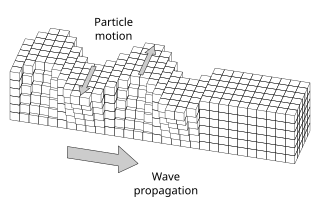

In physics, mathematics, engineering, and related fields, a wave is a propagating dynamic disturbance of one or more quantities. Periodic waves oscillate repeatedly about an equilibrium (resting) value at some frequency. When the entire waveform moves in one direction, it is said to be a travelling wave; by contrast, a pair of superimposed periodic waves traveling in opposite directions makes a standing wave. In a standing wave, the amplitude of vibration has nulls at some positions where the wave amplitude appears smaller or even zero. Waves are often described by a wave equation or a one-way wave equation for single wave propagation in a defined direction.

The propagation constant of a sinusoidal electromagnetic wave is a measure of the change undergone by the amplitude and phase of the wave as it propagates in a given direction. The quantity being measured can be the voltage, the current in a circuit, or a field vector such as electric field strength or flux density. The propagation constant itself measures the dimensionless change in magnitude or phase per unit length. In the context of two-port networks and their cascades, propagation constant measures the change undergone by the source quantity as it propagates from one port to the next.

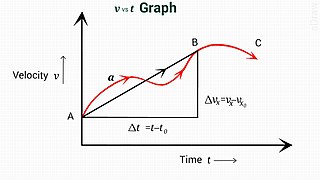

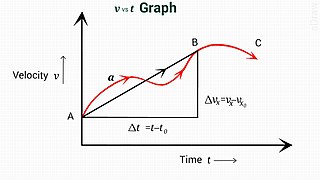

In physics, equations of motion are equations that describe the behavior of a physical system in terms of its motion as a function of time. More specifically, the equations of motion describe the behavior of a physical system as a set of mathematical functions in terms of dynamic variables. These variables are usually spatial coordinates and time, but may include momentum components. The most general choice are generalized coordinates which can be any convenient variables characteristic of the physical system. The functions are defined in a Euclidean space in classical mechanics, but are replaced by curved spaces in relativity. If the dynamics of a system is known, the equations are the solutions for the differential equations describing the motion of the dynamics.

Kinematics is a subfield of physics and mathematics, developed in classical mechanics, that describes the motion of points, bodies (objects), and systems of bodies without considering the forces that cause them to move. Kinematics, as a field of study, is often referred to as the "geometry of motion" and is occasionally seen as a branch of both applied and pure mathematics since it can be studied without considering the mass of a body or the forces acting upon it. A kinematics problem begins by describing the geometry of the system and declaring the initial conditions of any known values of position, velocity and/or acceleration of points within the system. Then, using arguments from geometry, the position, velocity and acceleration of any unknown parts of the system can be determined. The study of how forces act on bodies falls within kinetics, not kinematics. For further details, see analytical dynamics.

A phonon is a collective excitation in a periodic, elastic arrangement of atoms or molecules in condensed matter, specifically in solids and some liquids. A type of quasiparticle in physics, a phonon is an excited state in the quantum mechanical quantization of the modes of vibrations for elastic structures of interacting particles. Phonons can be thought of as quantized sound waves, similar to photons as quantized light waves.

In fluid dynamics, Stokes' law is an empirical law for the frictional force – also called drag force – exerted on spherical objects with very small Reynolds numbers in a viscous fluid. It was derived by George Gabriel Stokes in 1851 by solving the Stokes flow limit for small Reynolds numbers of the Navier–Stokes equations.

A normal mode of a dynamical system is a pattern of motion in which all parts of the system move sinusoidally with the same frequency and with a fixed phase relation. The free motion described by the normal modes takes place at fixed frequencies. These fixed frequencies of the normal modes of a system are known as its natural frequencies or resonant frequencies. A physical object, such as a building, bridge, or molecule, has a set of normal modes and their natural frequencies that depend on its structure, materials and boundary conditions.

In the physical science of dynamics, rigid-body dynamics studies the movement of systems of interconnected bodies under the action of external forces. The assumption that the bodies are rigid simplifies analysis, by reducing the parameters that describe the configuration of the system to the translation and rotation of reference frames attached to each body. This excludes bodies that display fluid, highly elastic, and plastic behavior.

Sound pressure or acoustic pressure is the local pressure deviation from the ambient atmospheric pressure, caused by a sound wave. In air, sound pressure can be measured using a microphone, and in water with a hydrophone. The SI unit of sound pressure is the pascal (Pa).

Particle velocity is the velocity of a particle in a medium as it transmits a wave. The SI unit of particle velocity is the metre per second (m/s). In many cases this is a longitudinal wave of pressure as with sound, but it can also be a transverse wave as with the vibration of a taut string.

Acoustic impedance and specific acoustic impedance are measures of the opposition that a system presents to the acoustic flow resulting from an acoustic pressure applied to the system. The SI unit of acoustic impedance is the pascal-second per cubic metre, or in the MKS system the rayl per square metre (Rayl/m2), while that of specific acoustic impedance is the pascal-second per metre (Pa·s/m), or in the MKS system the rayl (Rayl). There is a close analogy with electrical impedance, which measures the opposition that a system presents to the electric current resulting from a voltage applied to the system.

Particle displacement or displacement amplitude is a measurement of distance of the movement of a sound particle from its equilibrium position in a medium as it transmits a sound wave. The SI unit of particle displacement is the metre (m). In most cases this is a longitudinal wave of pressure, but it can also be a transverse wave, such as the vibration of a taut string. In the case of a sound wave travelling through air, the particle displacement is evident in the oscillations of air molecules with, and against, the direction in which the sound wave is travelling.

In physics, a wave vector is a vector used in describing a wave, with a typical unit being cycle per metre. It has a magnitude and direction. Its magnitude is the wavenumber of the wave, and its direction is perpendicular to the wavefront. In isotropic media, this is also the direction of wave propagation.

In the physical sciences and electrical engineering, dispersion relations describe the effect of dispersion on the properties of waves in a medium. A dispersion relation relates the wavelength or wavenumber of a wave to its frequency. Given the dispersion relation, one can calculate the frequency-dependent phase velocity and group velocity of each sinusoidal component of a wave in the medium, as a function of frequency. In addition to the geometry-dependent and material-dependent dispersion relations, the overarching Kramers–Kronig relations describe the frequency-dependence of wave propagation and attenuation.

In elastodynamics, Love waves, named after Augustus Edward Hough Love, are horizontally polarized surface waves. The Love wave is a result of the interference of many shear waves (S-waves) guided by an elastic layer, which is welded to an elastic half space on one side while bordering a vacuum on the other side. In seismology, Love waves (also known as Q waves (Quer: German for lateral)) are surface seismic waves that cause horizontal shifting of the Earth during an earthquake. Augustus Edward Hough Love predicted the existence of Love waves mathematically in 1911. They form a distinct class, different from other types of seismic waves, such as P-waves and S-waves (both body waves), or Rayleigh waves (another type of surface wave). Love waves travel with a lower velocity than P- or S- waves, but faster than Rayleigh waves. These waves are observed only when there is a low velocity layer overlying a high velocity layer/ sub–layers.

Acoustic waves are a type of energy propagation through a medium by means of adiabatic loading and unloading. Important quantities for describing acoustic waves are acoustic pressure, particle velocity, particle displacement and acoustic intensity. Acoustic waves travel with a characteristic acoustic velocity that depends on the medium they're passing through. Some examples of acoustic waves are audible sound from a speaker, seismic waves, or ultrasound used for medical imaging.

Geometrical acoustics or ray acoustics is a branch of acoustics that studies propagation of sound on the basis of the concept of acoustic rays, defined as lines along which the acoustic energy is transported. This concept is similar to geometrical optics, or ray optics, that studies light propagation in terms of optical rays. Geometrical acoustics is an approximate theory, valid in the limiting case of very small wavelengths, or very high frequencies. The principal task of geometrical acoustics is to determine the trajectories of sound rays. The rays have the simplest form in a homogeneous medium, where they are straight lines. If the acoustic parameters of the medium are functions of spatial coordinates, the ray trajectories become curvilinear, describing sound reflection, refraction, possible focusing, etc. The equations of geometric acoustics have essentially the same form as those of geometric optics. The same laws of reflection and refraction hold for sound rays as for light rays. Geometrical acoustics does not take into account such important wave effects as diffraction. However, it provides a very good approximation when the wavelength is very small compared to the characteristic dimensions of inhomogeneous inclusions through which the sound propagates.

In electromagnetism, a branch of fundamental physics, the matrix representations of the Maxwell's equations are a formulation of Maxwell's equations using matrices, complex numbers, and vector calculus. These representations are for a homogeneous medium, an approximation in an inhomogeneous medium. A matrix representation for an inhomogeneous medium was presented using a pair of matrix equations. A single equation using 4 × 4 matrices is necessary and sufficient for any homogeneous medium. For an inhomogeneous medium it necessarily requires 8 × 8 matrices.