Related Research Articles

The First Council of Nicaea was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

The First Council of Constantinople was a council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople in AD 381 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I. This second ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the church through an assembly representing all of Christendom, except for the Western Church, confirmed the Nicene Creed, expanding the doctrine thereof to produce the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, and dealt with sundry other matters. It met from May to July 381 in the Church of Hagia Irene and was affirmed as ecumenical in 451 at the Council of Chalcedon.

Eunomius, one of the leaders of the extreme or "anomoean" Arians, who are sometimes accordingly called Eunomians, was born at Dacora in Cappadocia or at Corniaspa in Pontus. early in the 4th century.

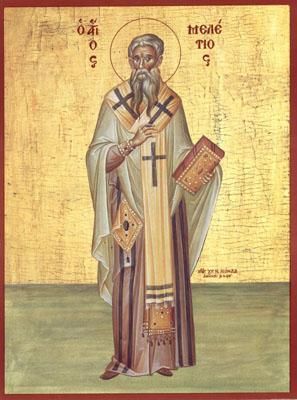

Saint Meletius was a Christian bishop of Antioch from 360 until his death in 381. However, his episcopate was dominated by a schism, usually called the Meletian schism.

Alexander of Constantinople was bishop of Byzantium from 314 and the first bishop of Constantinople from 330. Scholars consider most of the available information on Alexander to be legendary.

Paul I or Paulus I or Saint Paul the Confessor, was the sixth bishop of Constantinople, elected first in 337 AD. Paul became involved in the Arian controversy which drew in the Emperor of the West, Constans, and his counterpart in the East, his brother Constantius II. Paul was installed and deposed three times from the See of Constantinople between 337 and 351. He was murdered by strangulation during his third and final exile in Cappadocia. His feast day is on November 6.

Macedonius was a Greek bishop of Constantinople from 342 up to 346, and from 351 until 360. He inspired the establishment of the Pneumatomachi, a sect later declared heretical.

Eudoxius was the eighth bishop of Constantinople from January 27, 360 to 370, previously bishop of Germanicia and of Antioch. Eudoxius was one of the most influential Arians.

Nectarius was the archbishop of Constantinople from AD 381 until his death, the successor to Saint Gregory Nazianzus and predecessor to St. John Chrysostom.

The Councils of Sirmium were the five episcopal councils held in Sirmium in 347, 351, 357, 358 and finally in 375 or 378. The third—the most important of the councils—marked a temporary compromise between Arianism and the Western bishops of the Christian church. At least two of the other councils also dealt primarily with the Arian controversy. All of these councils were held under the rule of Constantius II, who was sympathetic to the Arians.

In 4th-century Christianity, the Anomoeans, and known also as Heterousians, Aetians, or Eunomians, were a sect that held to a form of Arianism, that Jesus Christ was not of the same nature (consubstantial) as God the Father nor was He of like or similar nature to God (homoiousian), as maintained by the semi-Arians.

Semi-Arianism was a position regarding the relationship between God the Father and the Son of God, adopted by some 4th-century Christians. Though the doctrine modified the teachings of Arianism, it still rejected the doctrine that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are co-eternal, and of the same substance, or consubstantial, and was therefore considered to be heretical by many contemporary Christians.

Marcellus of Ancyra was a Bishop of Ancyra and one of the bishops present at the Council of Ancyra and the First Council of Nicaea. He was a strong opponent of Arianism, but was accused of adopting the opposite extreme of modified Sabellianism. He was condemned by a council of his enemies and expelled from his see, though he was able to return there to live quietly with a small congregation in the last years of his life. He is also said to have destroyed the temple of Zeus Belos at Apamea.

The Council of Seleucia was an early Christian church synod at Seleucia Isauria.

The Arian controversy was a series of Christian disputes about the nature of Christ that began with a dispute between Arius and Athanasius of Alexandria, two Christian theologians from Alexandria, Egypt. The most important of these controversies concerned the relationship between the substance of God the Father and the substance of His Son.

In 359, the Roman Emperor Constantius II requested a church council, at Constantinople, of both the eastern and western bishops, to resolve the split at the Council of Seleucia. According to Socrates Scholasticus, only about 50 of the Eastern bishops, and an unspecified number of the western ones, actually attended.

Patrophilus was the Arian bishop of Scythopolis in the early-mid 4th century AD. He was an enemy of Athanasius who described him as a πνευματόμαχος or "fighter against the Holy Spirit". When Arius was exiled to Palestine in 323 AD, Patrophilus warmly welcomed him.

Ursacius was the bishop of Singidunum, during the middle of the 4th century. He played an important role during the evolving controversies surrounding the legacies of the Council of Nicaea and the theologian Arius, acting frequently in concert with his fellow bishops of the Diocese of Pannonia, Germinius of Sirmium and Valens of Mursa. Found at various times during their episcopal careers staking positions on both sides of the developing theological debate and internal Church politicking, Ursacius and his fellows were seen to vacillate according to the political winds.

Valens of Mursa was bishop of Mursa and a supporter of Homoian theology, which is often labelled as a form of Arianism, although semi-Arianism is probably more accurate.

Heortasius was a 4th-century bishop of Sardis and attendee at the Councils of Seleucia and Constantinople. He was a proto-Catholic who was sent into exile by the Semi-Arian faction following their victory at the afore-mentioned Councils.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : John Arendzen (1913). "Pneumatomachi". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia . New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : John Arendzen (1913). "Pneumatomachi". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia . New York: Robert Appleton Company. - ↑ ep. serap 1;Found here: Athanasius, and C. R. B. Shapland. The Letters of Saint Athanasius Concerning the Holy Spirit. Translated by C. R. B. Shapland. London: Epworth Press, 1951. pp. 63 of pdf; pp 60 of book Found online here: https://archive.org/details/TheLettersOfSaintAthanasiusConcerningTheHolySpirit/page/n9/mode/2up

- ↑ On the Holy Spirit against the Macedonians.

- ↑ Turcescu, Lucian (2005). "On the Holy Spirit: Against the Macedonians". Gregory of Nyssa and the Concept of Divine Persons. pp. 109–114. doi:10.1093/0195174259.003.0007. ISBN 0-19-517425-9.

- 1 2 John Arendzen Pneumatomachi. Article in Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), Charles Herbermann, (editor) . Robert Appleton Company. s:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Pneumatomachi

- 1 2 Michael Pomazansky. Orthodox dogmatic theology, Part I. God in Himself-2. The dogma of the Holy Trinity -The equality of honor and the Divinity of the Holy Spirit. from which is quoted: "However, the chief of the heretics who distorted the apostolic teaching concerning the Holy Spirit was Macedonius, who occupied the cathedra of Constantinople as archbishop in the 4th century and found followers for himself among former Arians and Semi-Arians. He called the Holy Spirit a creation of the Son, and a servant of the Father and the Son. Accusers of his heresy were Fathers of the Church like Sts. Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, Athanasius the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, Ambrose, Amphilocius, Diodores of Tarsus, and others, who wrote works against the heretics. The false teaching of Macedonius was refuted first in a series of local councils and finally at the Second Ecumenical Council . In preserving Orthodoxy, the Second Ecumenical Council completed the Nicaean Symbol of Faith with these words: “And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the Giver of Life, Who proceedeth from the Father, Who with the Father and the Son is equally worshipped and glorified, Who spake by the Prophets,” as well as those articles of the Creed which follow this in the Nicaean-Constantinopolitan Symbol of Faith".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wace, Henry; Piercy, William C., eds. Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century (1911, third edition) London: John Murray.

- ↑ Elwell, Walter A. ed. Evangelical Dictionary of Theology , 2ed. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic (2001) pp.291.

- 1 2 Philostorgius, recorded in Photius. Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 4, chapter 9 and book 8, chapter 17.

- 1 2 3 Socrates Scholasticus. Church History, book 2, chapter 45.

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus. Church History, book 2, chapter 45 and book 3, chapter 10.

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus. Church History, book 3, chapter 10.

- ↑ On the Holy Spirit

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus. Church History, book 2, chapters 16, 27, 38 & 42

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus. Church History, book 2, chapters 38 & 45

- ↑ Philostorgius, in Photius. Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 8, chapter 17

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus. Church History, book 2, chapters 38, 42 & 45

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus. Church History, book 2, chapters 39, 40, 42 & 45

- ↑ Socrates Scholasticus. Church History, book 1, chapter 8 and book 2, chapter 15