This page lists some links to ancient philosophy, namely philosophical thought extending as far as early post-classical history.

Chinese philosophy originates in the Spring and Autumn period and Warring States period, during a period known as the "Hundred Schools of Thought", which was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments. Although much of Chinese philosophy begun in the Warring States period, elements of Chinese philosophy have existed for several thousand years. Some can be found in the I Ching, an ancient compendium of divination, which dates back to at least 672 BCE.

Eastern philosophy includes the various philosophies that originated in East and South Asia, including Chinese philosophy, Japanese philosophy, Korean philosophy, and Vietnamese philosophy, which are dominant in East Asia; and Indian philosophy, which are dominant in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Tibet, Japan and Mongolia.

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics, ontology, logic, biology, rhetoric and aesthetics. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and later evolved into Roman philosophy.

Indian philosophy consists of philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. The philosophies are often called darśana meaning, "to see" or "looking at." Ānvīkṣikī means “critical inquiry” or “investigation." Unlike darśana, ānvīkṣikī was used to refer to Indian philosophies by classical Indian philosophers, such as Chanakya in the Arthaśāstra.

Nondualism includes a number of philosophical and spiritual traditions that emphasize the absence of fundamental duality or separation in existence. This viewpoint questions the boundaries conventionally imposed between self and other, mind and body, observer and observed, and other dichotomies that shape our perception of reality. As a field of study, nondualism delves into the concept of nonduality and the state of nondual awareness, encompassing a diverse array of interpretations, not limited to a particular cultural or religious context; instead, nondualism emerges as a central teaching across various belief systems, inviting individuals to examine reality beyond the confines of dualistic thinking.

Christianity and Hellenistic philosophies experienced complex interactions during the first to the fourth centuries.

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Platonic philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC – when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the new Academy – until the development of neoplatonism under Plotinus in the 3rd century. Middle Platonism absorbed many doctrines from the rival Peripatetic and Stoic schools. The pre-eminent philosopher in this period, Plutarch, defended the freedom of the will and the immortality of the soul. He sought to show that God, in creating the world, had transformed matter, as the receptacle of evil, into the divine soul of the world, where it continued to operate as the source of all evil. God is a transcendent being, who operates through divine intermediaries, which are the gods and daemons of popular religion. Numenius of Apamea combined Platonism with neopythagoreanism and other eastern philosophies, in a move which would prefigure the development of neoplatonism.

Alcinous was a Middle Platonist philosopher. He probably lived in the 2nd century AD, although nothing is known about his life. He is the author of The Handbook of Platonism, an epitome of Middle Platonism intended as a manual for teachers. He has, at times, been identified by some scholars with the 2nd century Middle Platonist Albinus.

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary Platonists do not necessarily accept all doctrines of Plato. Platonism has had a profound effect on Western thought. At the most fundamental level, Platonism affirms the existence of abstract objects, which are asserted to exist in a third realm distinct from both the sensible external world and from the internal world of consciousness, and is the opposite of nominalism. This can apply to properties, types, propositions, meanings, numbers, sets, truth values, and so on. Philosophers who affirm the existence of abstract objects are sometimes called Platonists; those who deny their existence are sometimes called nominalists. The terms "Platonism" and "nominalism" also have established senses in the history of philosophy. They denote positions that have little to do with the modern notion of an abstract object.

Antiochus of Ascalon was a 1st-century BC Platonist philosopher. He rejected skepticism, blended Stoic doctrines with Platonism, and was the first philosopher in the tradition of Middle Platonism.

Ancient Roman philosophy is philosophy as it was practiced in the Roman Republic and its successor state, the Roman Empire. Roman philosophy includes not only philosophy written in Latin, but also philosophy written in Greek in the late Republic and Roman Empire. Important early Latin-language writers include Lucretius, Cicero, and Seneca the Younger. Greek was a popular language for writing about philosophy, so much so that the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius chose to write his Meditations in Greek.

Hellenistic philosophy is Ancient Greek philosophy corresponding to the Hellenistic period in Ancient Greece, from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC to the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. The dominant schools of this period were the Stoics, the Epicureans and the Skeptics.

Eudorus of Alexandria was an ancient Greek philosopher, and a representative of Middle Platonism. He attempted to reconstruct Plato's philosophy in terms of Pythagoreanism.

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common ideas it maintains is monism, the doctrine that all of reality can be derived from a single principle, "the One".

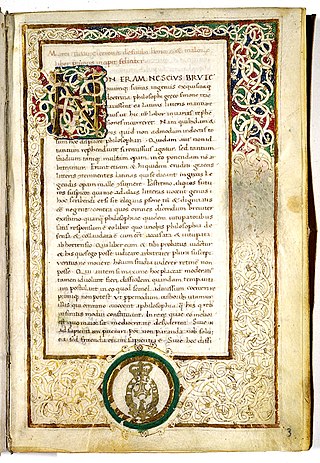

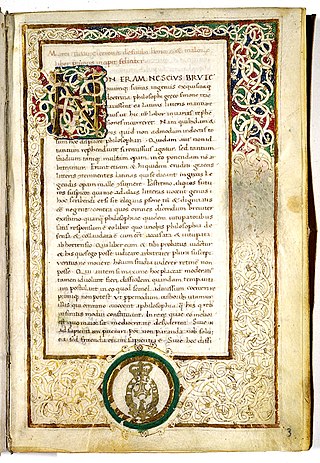

De finibus bonorum et malorum is a Socratic dialogue by the Roman orator, politician, and Academic Skeptic philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero. It consists of three dialogues, over five books, in which Cicero discusses the philosophical views of Epicureanism, Stoicism, and the Platonism of Antiochus of Ascalon. The treatise is structured so that each philosophical system is described in its own book, and then disputed in the following book. The book was developed in the summer of the year 45 BC, and was written over the course of about one and a half months. Together with the Tusculanae Quaestiones written shortly afterwards and the Academica, De finibus bonorum et malorum is one of the most extensive philosophical works of Cicero.

Academic skepticism refers to the skeptical period of the Academy dating from around 266 BCE, when Arcesilaus became scholarch, until around 90 BCE, when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected skepticism, although individual philosophers, such as Favorinus and his teacher Plutarch, continued to defend skepticism after this date. Unlike the existing school of skepticism, the Pyrrhonists, they maintained that knowledge of things is impossible. Ideas or notions are never true; nevertheless, there are degrees of plausibility, and hence degrees of belief, which allow one to act. The school was characterized by its attacks on the Stoics, particularly their dogma that convincing impressions led to true knowledge. The most important Academics were Arcesilaus, Carneades, and Philo of Larissa. The most extensive ancient source of information about Academic skepticism is Academica, written by the Academic skeptic philosopher Cicero.

Advaita Vedanta and Mahayana Buddhism share significant similarities. Those similarities have attracted Indian and Western scholars attention, and have also been criticised by concurring schools. The similarities have been interpreted as Buddhist influences on Advaita Vedanta, though some deny such influences, or see them as expressions of the same eternal truth.

Taoist philosophy also known as Taology refers to the various philosophical currents of Taoism, a tradition of Chinese origin which emphasizes living in harmony with the Dào. The Dào is a mysterious and deep principle that is the source, pattern and substance of the entire universe.