The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and its energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe.

In Greek mythology, the Cercopes (Greek: Κέρκωπες, plural of Κέρκωψ, from κέρκος (n.) kerkos "tail") were mischievous forest creatures who lived in Thermopylae or on Euboea but roamed the world and might turn up anywhere mischief was afoot. They were two brothers, but their names are given variously:

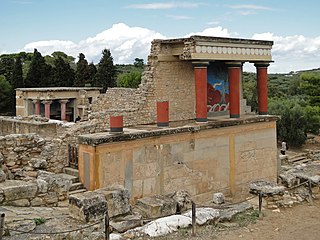

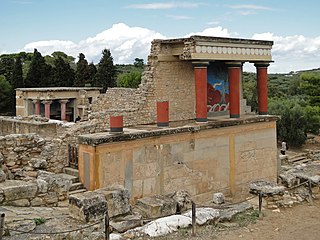

Knossos is a Bronze Age archaeological site in Crete. The site was a major center of the Minoan civilization and is known for its association with the Greek myth of Theseus and the minotaur. It is located on the outskirts of Heraklion, and remains a popular tourist destination.

Bull-leaping is a term for various types of non-violent bull fighting. Some are based on an ancient ritual from the Minoan civilization involving an acrobat leaping over the back of a charging bull. As a sport it survives in modern France, usually with cows rather than bulls, as course landaise; in Spain, with bulls, as recortes and in Tamil Nadu, India with bulls as Jallikattu.

Minoan pottery has been used as a tool for dating the mute Minoan civilization. Its restless sequence of quirky maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning relative dates to the strata of their sites. Pots that contained oils and ointments, exported from 18th century BC Crete, have been found at sites through the Aegean islands and mainland Greece, in Cyprus, along coastal Syria and in Egypt, showing the wide trading contacts of the Minoans.

The Heraklion Archaeological Museum is a museum located in Heraklion on Crete. It is one of the largest museums in Greece and the best in the world for Minoan art, as it contains by far the most important and complete collection of artefacts of the Minoan civilization of Crete. It is normally referred to scholarship in English as "AMH", a form still sometimes used by the museum in itself.

Two Minoan snake goddess figurines were excavated in 1903 in the Minoan palace at Knossos in the Greek island of Crete. The decades-long excavation programme led by the English archaeologist Arthur Evans greatly expanded knowledge and awareness of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization, but Evans has subsequently been criticised for overstatements and excessively speculative ideas, both in terms of his "restoration" of specific objects, including the most famous of these figures, and the ideas about the Minoans he drew from the archaeology. The figures are now on display at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum (AMH).

Minoan religion was the religion of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization of Crete. In the absence of readable texts from most of the period, modern scholars have reconstructed it almost totally on the basis of archaeological evidence of such as Minoan paintings, statuettes, vessels for rituals and seals and rings. Minoan religion is considered to have been closely related to Near Eastern ancient religions, and its central deity is generally agreed to have been a goddess, although a number of deities are now generally thought to have been worshipped. Prominent Minoan sacred symbols include the bull and the horns of consecration, the labrys double-headed axe, and possibly the serpent.

"Horns of Consecration" is a term coined by Sir Arthur Evans for the symbol, ubiquitous in Minoan civilization, that is usually thought to represent the horns of the sacred bull. Sir Arthur Evans concluded, after noting numerous examples in Minoan and Mycenaean contexts, that the Horns of Consecration were "a more or less conventionalised article of ritual furniture derived from the actual horns of the sacrificial oxen".

Minoan art is the art produced by the Bronze Age Aegean Minoan civilization from about 3000 to 1100 BC, though the most extensive and finest survivals come from approximately 2300 to 1400 BC. It forms part of the wider grouping of Aegean art, and in later periods came for a time to have a dominant influence over Cycladic art. Since wood and textiles have decomposed, the best-preserved surviving examples of Minoan art are its pottery, palace architecture, small sculptures in various materials, jewellery, metal vessels, and intricately-carved seals.

Tell el-Dab'a is an archaeological site in the Nile Delta region of Egypt where Avaris, the capital city of the Hyksos, once stood. Avaris was occupied by Asiatics from the end of the 12th through the 13th Dynasty. The site is known primarily for its Minoan frescoes.

Piet Christiaan Leonardus de Jong was an artist who worked on the illustration and reconstruction of archaeological sites in the Mediterranean, including Mycenae, Knossos, Eutresis, Gordion, and the Athenian Agora.

The Hagia Triada Sarcophagus is a late Minoan 137 cm (54 in)-long limestone sarcophagus, dated to around 1400 BC or some decades later, excavated from a chamber tomb at Hagia Triada, Crete in 1903 and now on display at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum (AMH) in Crete, Greece.

The bull-leaping fresco is the most completely restored of several stucco panels originally sited on the upper-story portion of the east wall of the Minoan palace at Knossos in Crete. It shows a bull-leaping scene. Although they were frescos, they were painted on stucco relief scenes. They were difficult to produce. The artist had to manage not only the altitude of the panel but also the simultaneous molding and painting of fresh stucco. The panels, therefore, do not represent the formative stages of the technique. In Minoan chronology, their polychrome hues – white, pale red, dark red, blue, black – exclude them from the Early Minoan (EM) and early Middle Minoan (MM) Periods. They are, in other words, instances of the "mature art" created no earlier than MM III. The flakes of the destroyed panels fell to the ground from the upper story during the destruction of the palace, probably by earthquake, in Late Minoan (LM) II. By that time the east stairwell, near which they fell, was disused, being partly ruinous.

Minoan seals are impression seals in the form of carved gemstones and similar pieces in metal, ivory and other materials produced in the Minoan civilization. They are an important part of Minoan art, and have been found in quantity at specific sites, for example in Knossos, Mallia and Phaistos. They were evidently used as a means of identifying documents and objects.

The Minoan bull leaper is a bronze group of a bull and leaper in the British Museum. It is the only known largely complete three-dimensional sculpture depicting Minoan bull-leaping. Although bull leaping certainly took place in Crete at this time, the leap depicted is practically impossible and it has therefore been speculated that the sculpture may be an exaggerated depiction. This speculation has been backed up by the testaments of modern-day bull leapers from France and Spain.

The Minoan wall paintings at Tell el-Dab'a are of particular interest to Egyptologists and archaeologists. They are of Minoan style, content, and technology, but there is uncertainty over the ethnic identity of the artists. The paintings depict images of bull-leaping, bull-grappling, griffins, and hunts. They were discovered by a team of archaeologists led by Manfred Bietak, in the palace district of the Thutmosid period at Tell el-Dab'a. The frescoes date to the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt, most likely during the reigns of either the pharaohs Hatshepsut or Thutmose III, after being previously considered to belong to the late Second Intermediate Period. The paintings indicate an involvement of Egypt in international relations and cultural exchanges with the Eastern Mediterranean either through marriage or exchange of gifts.

The Throne Room was a chamber built for ceremonial purposes during the 15th century BC inside the palatial complex of Knossos, Crete, in Greece. It is found at the heart of the Bronze Age palace of Knossos, one of the main centers of the Minoan civilization and is considered the oldest throne room in Europe.

Louis Émile Emmanuel Gilliéron (1850–1924), often known as Émile Gilliéronpère to distinguish him from his son, was a Swiss artist and archaeological draughtsman best known for his reconstructions of Mycenaean and Minoan artefacts from the Bronze Age. From 1877 until his death, he worked with archaeologists such as Heinrich Schliemann, Arthur Evans and Georg Karo, drawing and restoring ancient objects from sites such as the Acropolis of Athens, Mycenae, Tiryns and Knossos. Well-known discoveries reconstructed by Gilliéron include the "Harvester Vase", the "Priest-King Fresco" and the "Bull-Leaping Fresco".

Nanno (Ourania) Marinatos is Professor Emerita of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies at the University of Illinois Chicago, whose research focuses on the Minoan civilisation, especially Minoan religion.