Aegean civilization is a general term for the Bronze Age civilizations of Greece around the Aegean Sea. There are three distinct but communicating and interacting geographic regions covered by this term: Crete, the Cyclades and the Greek mainland. Crete is associated with the Minoan civilization from the Early Bronze Age. The Cycladic civilization converges with the mainland during the Early Helladic ("Minyan") period and with Crete in the Middle Minoan period. From c. 1450 BC, the Greek Mycenaean civilization spreads to Crete, probably by military conquest. The earlier Aegean farming populations of Neolithic Greece brought agriculture westward into Europe before 5000 BC.

Linear A is a writing system that was used by the Minoans of Crete from 1800 BC to 1450 BC. Linear A was the primary script used in palace and religious writings of the Minoan civilization. It evolved into Linear B, which was used by the Mycenaeans to write an early form of Greek. It was discovered by the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans in 1900. No texts in Linear A have yet been deciphered. Evans named the script "Linear" because its characters consisted simply of lines inscribed in clay, in contrast to the more pictographic characters in Cretan hieroglyphs that were used during the same period.

Linear B is a syllabic script that was used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest attested form of the Greek language. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries, the earliest known examples dating to around 1450 BC. It is adapted from the earlier Linear A, an undeciphered script perhaps used for writing the Minoan language, as is the later Cypriot syllabary, which also recorded Greek. Linear B, found mainly in the palace archives at Knossos, Kydonia, Pylos, Thebes and Mycenae, disappeared with the fall of Mycenaean civilization during the Late Bronze Age collapse. The succeeding period, known as the Greek Dark Ages, provides no evidence of the use of writing.

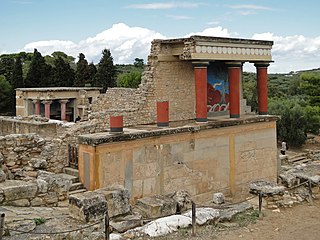

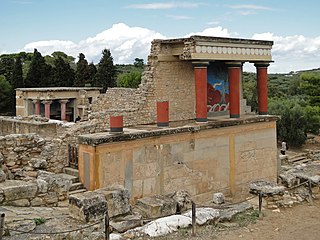

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe. The ruins of the Minoan palaces at Knossos and Phaistos are popular tourist attractions.

Phaistos, also transliterated as Phaestos, Festos and Latin Phaestus, is a Bronze Age archaeological site at modern Faistos, a municipality in south central Crete. It is notable for the remains of a Minoan palace and the surrounding town.

Gournia is the site of a Minoan palace complex in the Lasithi regional unit on the island of Crete, Greece. Its modern name originated from the many stone troughs that are at the site and its original name for the site is unknown. It was first permanently inhabited during the Early Minoan II periods and was occupied until the Late Minoan I period. Gournia is in a 6 mile cluster of with other Minoan archeological sites which includes Pachyammos, Vasiliki, Monasteraki, Vraika and Kavusi. The site of Pseira is close but slightly outside the cluster.

Spyridon Marinatos was a Greek archaeologist who specialised in the Bronze Age Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. He is best known for the excavation of the Minoan site of Akrotiri on Santorini, which he conducted between 1967 and 1974. A recipient of several honours in Greece and abroad, he was considered one of the most important Greek archaeologists of his day.

The Minoan civilization produced a wide variety of richly decorated Minoan pottery. Its restless sequence of quirky maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning relative dates to the strata of their sites. Pots that contained oils and ointments, exported from 18th century BC Crete, have been found at sites through the Aegean islands and mainland Greece, in Cyprus, along coastal Syria and in Egypt, showing the wide trading contacts of the Minoans.

Hagia Triada, is a Minoan archaeological site in Crete. The site includes the remains of an extensive settlement noted for its monumental NeoPalatial and PostPalatial period buildings especially the large Royal Villa. It is located in the Mesara Plain about three kilometers from the larger Palace of Phaistos, with which it appears to have had close political and economic ties. It is also nearby the Minoan harbor site of Kommos. Excavations at Hagia Triada have provided crucial evidence concerning Minoan everyday life.

Mochlos is a small, uninhabited island in the Gulf of Mirabello in eastern Crete, and the archaeological site of an ancient Minoan settlement. There is evidence that Mochlos was not an island in Minoan times, but was attached to the mainland and acted as an eastern harbor.

Cretan hieroglyphs are a hieroglyphic writing system used in early Bronze Age Crete, during the Minoan era. They predate Linear A by about a century, but the two writing systems continued to be used in parallel for most of their history. As of 2024, they are undeciphered.

Kydonia, also known as Cydonia was an ancient city located at the site of present-day Chania on the island of Crete in Greece. The city is known from archaeological remains dating back to the Minoan era as well as literary and historical sources.

Minoan chronology is a framework of dates used to divide the history of the Minoan civilization. Two systems of relative chronology are used for the Minoans. One is based on sequences of pottery styles, while the other is based on the architectural phases of the Minoan palaces. These systems are often used alongside one another.

Nikolaos Platon was a Greek archaeologist. He discovered the Minoan palace of Zakros on Crete.

Mycenaean pottery is the pottery tradition associated with the Mycenaean period in Ancient Greece. It encompassed a variety of styles and forms including the stirrup jar. The term "Mycenaean" comes from the site Mycenae, and was first applied by Heinrich Schliemann.

Kamares ware is a distinctive style of Minoan pottery produced by the Minoans in Crete. It is recognizable by its light-on-dark decoration, with white, red, and orange abstract motifs painted over a black background. A prestige style that required high level craftsmanship, it is suspected to have been used as elite tableware. The finest pieces are so thin they are known as "eggshell ware".

Minoan palaces were massive building complexes built on Crete during the Bronze Age. They are often considered emblematic of the Minoan civilization and are modern tourist destinations. Archaeologists generally recognize five structures as palaces, namely those at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, Galatas, and Zakros. Minoan palaces consisted of multistory wings surrounding an open rectangular central court. They shared a common architectural vocabulary and organization, including distinctive room types such as the lustral basin and the pillar crypt. However, each palace was unique, and their appearances changed dramatically as they were continually remodeled throughout their lifespans.

Phylakopi, located at the northern coast of the island of Milos, is one of the most important Bronze Age settlements in the Aegean and especially in the Cyclades. The importance of Phylakopi is in its continuity throughout the Bronze Age and because of this, it is the type-site for the investigation of several chronological periods of the Aegean Bronze Age.

Kavousi Vronda is an archaeological site in eastern Crete, Greece, located about 1.25 km south of the modern village of Kavousi, a historic village in the municipality of Ierapetra in the prefecture of Lasithi.

Malia is a Minoan and Mycenaean archaeological site located on the northern coast of Crete in the Heraklion area. It is about 35 kilometers east of the ancient site of Knossos and 40 kilometers east of the modern city of Heraklion. The site lies about 3 kilometers east and inland from the modern village of Malia. It was occupied from the middle 3rd millennium BC until about 1250 BC. During the Late Minoan I period it had the third largest Minoan palace, destroyed at the end of the Late Minoan IB period. The other palaces are at Hagia Triada, Knossos, Phaistos, Zakros, and Gournia. It has been excavated for over a century by the French School of Athens and inscriptions of the undeciphered scripts Cretan hieroglyphs, Linear A, and the deciphered script Linear B have been found there.