The Roman legion, the largest military unit of the Roman army, was composed of Roman citizens serving as legionaries. During the Roman Republic the manipular legion comprised 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. After the Marian reforms in 107 BC, the legions were formed of 5,200 men and were restructured around 10 cohorts, the first cohort being double strength. This structure persisted throughout the Principate and middle Empire, before further changes in the fourth century resulted in new formations of around 1,000 men.

The Battle of Zama was fought in 202 BC in what is now Tunisia between a Roman army commanded by Scipio Africanus and a Carthaginian army commanded by Hannibal. The battle was part of the Second Punic War and resulted in such a severe defeat for the Carthaginians that they capitulated, while Hannibal was forced into exile. The Roman army of approximately 30,000 men was outnumbered by the Carthaginians who fielded either 40,000 or 50,000; the Romans were stronger in cavalry, but the Carthaginians had 80 war elephants.

The Battle of the Trebia was the first major battle of the Second Punic War, fought between the Carthaginian forces of Hannibal and a Roman army under Sempronius Longus on 22 or 23 December 218 BC. Each army had a strength of about 40,000 men; the Carthaginians were stronger in cavalry, the Romans in infantry. The battle took place on the flood plain of the west bank of the lower Trebia River, not far from the settlement of Placentia, and resulted in a heavy defeat for the Romans.

A cohort was a standard tactical military unit of a Roman legion. Although the standard size changed with time and situation, it was generally composed of 480 soldiers. A cohort is considered to be the equivalent of a modern military battalion. The cohort replaced the maniple. From the late second century BC and until the middle of the third century AD, ten cohorts made up a legion. Cohorts were named "first cohort", "second cohort", etc. The first cohort consisted of experienced legionaries, while the legionaries in the tenth cohort were less experienced.

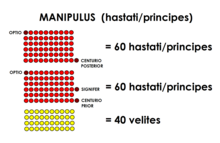

Maniple was a tactical unit of the Roman Republican armies, adopted during the Samnite Wars. It was also the name of the military insignia carried by such units.

Rorarii were soldiers who formed the final lines, or else provided a reserve thereby, in the ancient pre-Marian Roman army. They may have been used with the triarii in battle near the final stages of fighting, since they are recorded as being located at the rear of the main battle formation.

The Battle of Telamon was fought between the Roman Republic and an alliance of Celtic tribes in 225 BC. The Romans, led by the consuls Gaius Atilius Regulus and Lucius Aemilius Papus, defeated the Celts led by the Gaesatae kings Concolitanus and Aneroëstes. This removed the Celtic threat from Rome and allowed the Romans to extend their influence over northern Italy.

The term accensi is applied to two different groups. Originally, the accensi were light infantry in the armies of the early Roman Republic. They were the poorest men in the legion, and could not afford much equipment. They did not wear armour or carry shields, and their usual position was part of the third battle line. They fought in a loose formation, supporting the heavier troops. They were eventually phased out by the time of Second Punic War. In the later Roman Republic the term was used for civil servants who assisted the elected magistrates, particularly in the courts, where they acted as ushers and clerks.

The structural history of the Roman military concerns the major transformations in the organization and constitution of ancient Rome's armed forces, "the most effective and long-lived military institution known to history." At the highest level of structure, the forces were split into the Roman army and the Roman navy, although these two branches were less distinct than in many modern national defense forces. Within the top levels of both army and navy, structural changes occurred as a result of both positive military reform and organic structural evolution. These changes can be divided into four distinct phases.

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon. Today, the javelin is predominantly used for sporting purposes such as the javelin throw. The javelin is nearly always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the aid of a hand-held mechanism. However, devices do exist to assist the javelin thrower in achieving greater distances, such as spear-throwers or the amentum.

The verutum, plural veruta, was a short javelin used in the Roman army. This javelin was used by the velites for skirmishing purposes, unlike the heavier pilum, which was used by the hastati and principes for weakening the enemy before advancing into close combat. The shafts were about 1.1 metres long, substantially shorter than the 2-metre pilum, and the point measured about 13 centimetres (5 in) long. The verutum had either an iron shank like the pilum or a tapering metal head. It was sometimes thrown with the aid of a throwing strap, or amentum.

Heavy infantry consisted of heavily armed and armoured infantrymen who were trained to mount frontal assaults and/or anchor the defensive center of a battle line. This differentiated them from light infantry who were relatively mobile and lightly armoured skirmisher troops intended for screening, scouting, and other tactical roles unsuited to soldiers carrying heavier loads. Heavy infantry typically made use of dense battlefield formations, such as shield wall or phalanx, multiplying their effective weight of arms with force concentration.

Velites were a class of infantry in the Roman army of the mid-Republic from 211 to 107 BC. Velites were light infantry and skirmishers armed with javelins, each with a 75cm wooden shaft the diameter of a finger, with a 25cm narrow metal point, to fling at the enemy. They also carried short thrusting swords, or gladii, for use in melee. They rarely wore armour as they were the youngest and poorest soldiers in the legion and could not afford much equipment. They did carry small wooden shields called parma for protection, and wore headdresses made from wolf skins so their brave deeds could be recognized. The velites were placed at the front partly for tactical reasons, and also so that they had the opportunity to secure glory for themselves in single combat.

Hastati were a class of infantry employed in the armies of the early Roman Republic, who originally fought as spearmen and later as swordsmen. These soldiers were the staple unit after Rome threw off Etruscan rule. They were originally some of the poorest men in the legion, and could afford only modest equipment—light chainmail and other miscellaneous equipment. The Senate supplied their soldiers with only a short stabbing sword, the gladius, and their distinctive squared shield, the scutum. The hastatus was typically equipped with these, and one or two soft iron tipped throwing spears called pila. This doubled their effectiveness, not only as a strong leading edge to their maniple, but also as a stand-alone missile troop. Later, the hastati contained the younger men rather than just the poorer, though most men of their age were relatively poor. Their usual position was the first battle line. They fought in a quincunx formation, supported by lighter infantry. The enemy was allowed to penetrate the first battle line consisting of hastati, after which the enemy would deal with the more hardened, seasoned soldiers, the principes. They were eventually disbanded after the so-called "Marian reforms" of 107 BC.

Triarii were one of the elements of the early Roman military manipular legions of the early Roman Republic. They were the oldest and among the wealthiest men in the army and could afford high quality equipment. They wore heavy metal armor and carried large shields, their usual position being the third battle line. They were equipped with spears and were considered to be elite soldiers among the legion.

Leves were javelin-armed skirmishers in the army of the early Roman Republic. They were typically some of the youngest and poorest men in the legion, and could not afford much equipment. They were usually outfitted with just a number of light javelins and no other equipment. There were 300 leves in a legion, and unlike other infantry types they did not form their own units, but were assigned to units of hastati – heavier sword-armed troops. Their primary purpose on the battlefield was to harass the enemy with javelin fire and support the heavy infantry who fought in hand-to-hand combat. Accensi and rorarii were also light missile troops and had similar roles.

The Roman army of the mid-Republic, also called the manipular Roman army or the Polybian army, refers to the armed forces deployed by the mid-Roman Republic, from the end of the Samnite Wars to the end of the Social War. The first phase of this army, in its manipular structure, is described in detail in the Histories of the ancient Greek historian Polybius, writing before 146 BC.

The Roman army of the late Republic refers to the armed forces deployed by the late Roman Republic, from the beginning of the first century BC until the establishment of the Imperial Roman army by Augustus in 30 BC.

Roman infantry tactics are the theoretical and historical deployment, formation, and manoeuvres of the Roman infantry from the start of the Roman Republic to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The original Roman army was made up of hoplites, whose main strategy was forming into a phalanx. By the early third century BCE, the Roman army would switch to the maniple system, which would divide the Roman army into three units, hastati, principes, and triarii. Later, in 107 BCE, Marius would institute the so-called Marian reforms, creating the Roman legions. This system would evolve into the Late Roman Army, which utilized the comitatenses and limitanei units to defend the Empire.