The cursus honorum was the sequential order of public offices held by aspiring politicians in the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. It was designed for men of senatorial rank. The cursus honorum comprised a mixture of military and political administration posts; the ultimate prize for winning election to each "rung" in the sequence was to become one of the two consuls in a given year. Each office had a minimum age for election; there were also minimum intervals between holding successive offices and laws forbade repeating an office.

Praetor, also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected magistratus (magistrate), assigned to discharge various duties. The functions of the magistracy, the praetura (praetorship), are described by the adjective: the praetoria potestas, the praetorium imperium, and the praetorium ius, the legal precedents established by the praetores (praetors). Praetorium, as a substantive, denoted the location from which the praetor exercised his authority, either the headquarters of his castra, the courthouse (tribunal) of his judiciary, or the city hall of his provincial governorship.

The First Triumvirate was an informal political alliance among three prominent politicians in the late Roman Republic: Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus. The constitution of the Roman republic had many veto points. In order to bypass constitutional obstacles and force through the political goals of the three men, they forged in secret an alliance where they promised to use their respective influence to support each other. The "triumvirate" was not a formal magistracy, nor did it achieve a lasting domination over state affairs.

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus was a reformist Roman politician in the 2nd century BC. He is most famous for his tribunate for the years 123 and 122 BC, in which he proposed a wide set of laws, including laws to establish colonies outside of Italy, engage in further land reform, reform the judicial system, and create a subsidised grain supply for Rome.

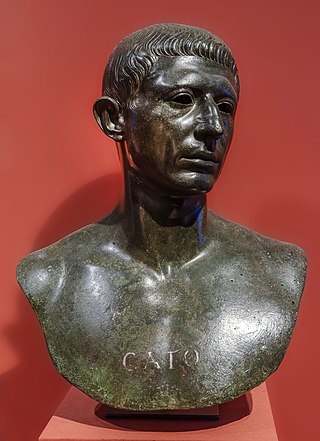

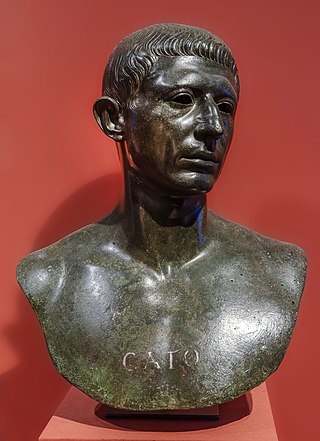

Marcus Porcius Cato "Uticensis", also known as Cato the Younger, was an influential conservative Roman senator during the late Republic. His conservative principles were focused on the preservation of what he saw as old Roman values in decline. A noted orator and a follower of Stoicism, his scrupulous honesty and professed respect for tradition gave him a powerful political following which he mobilised against powerful generals of his day.

The Roman provinces were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as governor.

In ancient Rome a promagistrate was an ex-consul or ex-praetor whose imperium was extended at the end of his annual term of office or later. They were called proconsuls and propraetors. This was an innovation created during the Roman Republic. Initially it was intended to provide additional military commanders to support the armies of the consuls or to lead an additional army. With the acquisitions of territories outside Italy which were annexed as provinces, proconsuls and propraetors became provincial governors or administrators. A third type of promagistrate were the proquaestors.

A Roman dictator was an extraordinary magistrate in the Roman Republic endowed with full authority to resolve some specific problem to which he had been assigned. He received the full powers of the state, subordinating the other magistrates, consuls included, for the specific purpose of resolving that issue, and that issue only, and then dispensing with those powers forthwith.

Prorogation in the Westminster system of government is the action of proroguing, or interrupting, a parliament, or the discontinuance of meetings for a given period of time, without a dissolution of parliament. The term is also used for the period of such a discontinuance between two legislative sessions of a legislative body.

The senatus consultum ultimum is the modern term given to resolutions of the Roman Senate lending its moral support for magistrates to use the full extent of their powers and ignore the laws to safeguard the state.

The Curiate Assembly was the principal assembly that evolved in shape and form over the course of the Roman Kingdom until the Comitia Centuriata organized by Servius Tullius. During these first decades, the people of Rome were organized into thirty units called "Curiae". The Curiae were ethnic in nature, and thus were organized on the basis of the early Roman family, or, more specifically, on the basis of the thirty original patrician (aristocratic) clans. The Curiae formed an assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Curiate Assembly passed laws, elected Consuls, and tried judicial cases. Consuls always presided over the assembly. While plebeians (commoners) could participate in this assembly, only the patricians could vote.

A consular tribune was putatively a type of magistrate in the early Roman Republic. According to Roman tradition, colleges of consular tribunes held office throughout the fifth and fourth centuries BC during the so-called "Conflict of the Orders". The ancient historian Livy offered two explanations: the Roman state could have needed more magistrates to support its military endeavours; alternatively, the consular tribunate was offered in lieu of the ordinary consulship to plebeians so to maintain a patrician lock on the consulship.

The Roman magistrates were elected officials in Ancient Rome.

The constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of uncodified norms and customs which, together with various written laws, guided the procedural governance of the Roman Republic. The constitution emerged from that of the Roman kingdom, evolved substantively and significantly—almost to the point of unrecognisability—over the almost five hundred years of the republic. The collapse of republican government and norms from 133 BC would lead to the rise of Augustus and his principate.

Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos was an ancient Roman politician during the Late Republic. He was a son of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos and served as tribune of the plebs in 62 BC, consul in 57 BC, and the governor of Hispania Citerior from 56–55 BC.

The executive magistrates of the Roman Republic were officials of the ancient Roman Republic, elected by the People of Rome. Ordinary magistrates (magistratus) were divided into several ranks according to their role and the power they wielded: censors, consuls, praetors, curule aediles, and finally quaestor. Any magistrate could obstruct (veto) an action that was being taken by a magistrate with an equal or lower degree of magisterial powers. By definition, plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles were technically not magistrates as they were elected only by the plebeians, but no ordinary magistrate could veto any of their actions. Dictator was an extraordinary magistrate normally elected in times of emergency for a short period. During this period, the dictator's power over the Roman government was absolute, as they were not checked by any institution or magistrate.

The executive magistrates of the Roman Empire were elected individuals of the ancient Roman Empire. During the transition from monarchy to republic, the constitutional balance of power shifted from the executive to the Roman Senate. During the transition from republic to empire, the constitutional balance of power shifted back to the executive. Theoretically, the senate elected each new emperor, although in practice, it was the army which made the choice. The powers of an emperor, existed, in theory at least, by virtue of his legal standing. The two most significant components to an emperor's imperium were the "tribunician powers" and the "proconsular powers". In theory at least, the tribunician powers gave the emperor authority over Rome's civil government, while the proconsular powers gave him authority over the Roman army. While these distinctions were clearly defined during the early empire, eventually they were lost, and the emperor's powers became less constitutional and more monarchical.

Quintus Minucius Rufus was a Roman senator and military commander.

Marcus Baebius Tamphilus was a consul of the Roman Republic in 181 BC along with P. Cornelius Cethegus. Baebius is credited with reform legislation pertaining to campaigns for political offices and electoral bribery (ambitus). The Lex Baebia was the first bribery law in Rome and had long-term impact on Roman administrative practices in the provinces.

Roman Republican governors of Gaul were assigned to the province of Cisalpine Gaul or to Transalpine Gaul, the Mediterranean region of present-day France also called the Narbonensis, though the latter term is sometimes reserved for a more strictly defined area administered from Narbonne. Latin Gallia can also refer in this period to greater Gaul independent of Roman control, covering the remainder of France, Belgium, and parts of the Netherlands and Switzerland, often distinguished as Gallia Comata and including regions also known as Celtica, Aquitania, Belgica, and Armorica (Brittany). To the Romans, Gallia was a vast and vague geographical entity distinguished by predominately Celtic inhabitants, with "Celticity" a matter of culture as much as speaking gallice.