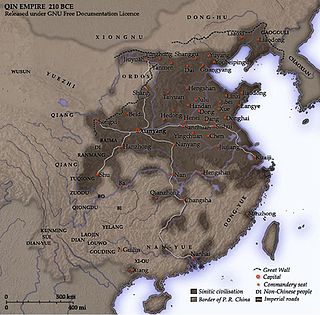

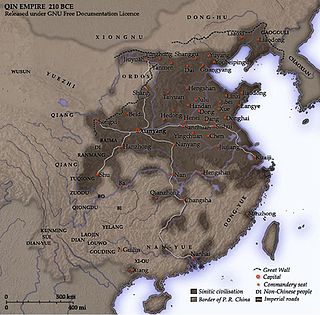

The Qin dynasty, or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization, was the first dynasty of Imperial China, lasting from 221 to 206 BC. Named for its heartland in Qin state, the dynasty was founded by Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of Qin. The strength of the Qin state was greatly increased by the Legalist reforms of Shang Yang in the fourth century BC, during the Warring States period. In the mid and late third century BC, the Qin state carried out a series of swift conquests, first ending the powerless Zhou dynasty and eventually conquering the other six of the Seven Warring States. Its 15 years was the shortest major dynasty in Chinese history, consisting of only two emperors, and its territory was the Yellow and Yangzi river heartland, not the modern China familiar from our maps. Despite its short reign, however, the lessons and strategies of the Qin shaped the Han dynasty and became the starting point of the Chinese imperial system that lasted from 221 BC, with interruption, development, and adaptation, until 1912 AD.

Year 209 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Verrucosus and Flaccus. The denomination 209 BC for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

The Baiyue, Hundred Yue, or simply Yue, were various ethnic groups who inhabited the regions of South China and Northern Vietnam during the 1st millennium BC and 1st millennium AD. They were known for their short hair, body tattoos, fine swords, and naval prowess.

Zhao Tuo, was a Qin dynasty Chinese general and first emperor of Nanyue. He participated in the conquest of the Baiyue peoples of Guangdong, Guangxi and Northern Vietnam. After the fall of the Qin, he established the independent kingdom of Nanyue with its capital in Panyu in 204 BCE. Some traditional Vietnamese history scholars considered him an emperor of Vietnam and the founder of the Triệu dynasty, other historians contested that he was a foreign invader.

Nanyue, was an ancient kingdom ruled by Chinese monarchs of the Zhao family that covered the modern Chinese subdivisions of Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Hong Kong, Macau, southern Fujian and central to northern Vietnam. Nanyue was established by Zhao Tuo, then Commander of Nanhai of Qin Empire, in 204 BC after the collapse of the Qin dynasty. At first, it consisted of the commanderies Nanhai, Guilin, and Xiang.

Zhao Mo was the grandson and successor of Zhao Tuo, and the second ruler of Nanyue, a kingdom encompassing parts of modern-day southern China and northern Vietnam. His rule began in 137 BC and ended with his death in 124 BC.

The Triệu dynasty ruled the kingdom of Nanyue, which consisted of parts of southern China as well as northern Vietnam. Its capital was Panyu, in modern Guangzhou. The founder of the dynasty, Zhao Tuo, was a Chinese general from Hebei and originally served as a military governor under the Qin dynasty. He asserted his independence in 207 BC as the Qin dynasty was collapsing. The ruling elite included both native Yue and immigrant Han peoples. Zhao Tuo conquered the Vietnamese state of Âu Lạc and led a coalition of Yuè states in a war against the Han dynasty, which had been expanding southward. Subsequent rulers were less successful in asserting their independence and the Han dynasty finally conquered the kingdom in 111 BC.

The First Era of Northern Domination refers to the period of Vietnamese history during which present-day northern Vietnam was under the rule of the Han dynasty and the Xin dynasty. It is considered the first of four periods of Vietnam under Chinese rule, the first three of which were almost continuous and referred to as Bắc thuộc.

The History of Hong Kong under Imperial China began in 214 BC during the Qin dynasty. The territory remained largely unoccupied until the later years of the Qing dynasty when Imperial China ceded the region to Great Britain under the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, whereupon Hong Kong became a British Colony.

Long Biên (Vietnamese), also known as Longbian was the capital of the Chinese Jiao Province and Jiaozhi Commandery during the Han dynasty. It was located on the Red River in modern-day Bac Ninh. After Ly Bi's successful revolt in AD 544, it served as the capital of Van Xuan. When the Sui dynasty of China retook the territory in 603, the Sui general Liu Fang moved the capital to nearby Tống Bình. Long Biên flourished as a trading port in the late 8th and early 9th centuries. Thăng Long was founded in 1010 at the site of earlier Chinese fortresses nearby. This grew into modern Hanoi, which incorporated Long Biên as one of its districts.

The Âu Việt or Ouyue were an ancient conglomeration of Baiyue tribes living in what is today the mountainous regions of northernmost Vietnam, western Guangdong, and northern Guangxi, China, since at least the third century BCE. They were believed to have belonged to the Tai-Kadai language group. In the legends of the Tay people, the western part of Âu Việt's land became the Nam Cương Kingdom, whose capital was located in what is today the Cao Bằng Province of Northeast Vietnam. In eastern China, the Ouyue established the Dong'ou or Eastern Ou kingdom. The Western Ou were other Baiyue tribes, with short hair and tattoos, who blackened their teeth and are the ancestors of the upland Tai-speaking minority groups in Vietnam such as the Nùng and Tay, as well as the closely related Zhuang people of Guangxi.

The Museum of the Western Han Dynasty Mausoleum of the Nanyue King houses the 2,000-year-old tomb of the Nanyue King Zhao Mo in Guangzhou. Zhao Mo ruled from 137 BC to 122 BC, and his tomb was discovered in downtown Guangzhou in 1983. The museum, which opened in 1988, showcases the tomb and its complete trove of artifacts. It was named a Major National Historical Site in 1996 and is renowned for its rare assemblage of funerary artifacts representing the diffusion of cultures throughout the Lingnan region during the Han dynasty.

Zhao Yingqi was the son of Zhao Mo and the third ruler of the kingdom of Nanyue. His rule began in 122 BC and ended with his death in 115 BC.

Zhao Xing, was the second son of Zhao Yingqi and the fourth ruler of Nanyue. His rule began in 115 BC and ended with his death in 112 BC.

Zhao Jiande was the last king of Nanyue. His rule began in 112 BC and ended in the next year.

Sawgoek or sawva was a mythological ancient script mentioned in the Zhuang creation epic Baeu Rodo. The primordial god Baeu Ro was said to have brought sawgoek containing four thousand glyphs along with fire to the Zhuang people. However, in their unfamiliarity with fire, the people stored the fire under a thatched roof, causing the house to catch on fire. The sawgoek was consumed in the ensuing conflagration, and knowledge of writing was lost. Some Zhuang scholars believe that this myth stems from a vague remembrance of sawgoek in the collective consciousness of the Zhuang people long after knowledge of the writing system had been forgotten.

The Han conquest of Nanyue was a military conflict between the Han Empire and the Nanyue kingdom in modern Guangdong, Guangxi, and Northern Vietnam. During the reign of Emperor Wu, the Han forces launched a punitive campaign against Nanyue and conquered it in 111 BC.

The Southward expansion of the Han dynasty was a series of Chinese military campaigns and expeditions in what is now modern Southern China and Northern Vietnam. Military expansion to the south began under the previous Qin dynasty and continued during the Han era. Campaigns were dispatched to conquer the Yue tribes, leading to the annexation of Minyue by the Han in 135 BC and 111 BC, Nanyue in 111 BC, and Dian in 109 BC.

The Han campaigns against Minyue were a series of three Han military campaigns dispatched against the Minyue state. The first campaign was in response to Minyue's invasion of Eastern Ou in 138 BC. In 135 BC, a second campaign was sent to intervene in a war between Minyue and Nanyue. After the campaign, Minyue was partitioned into Minyue, ruled by a Han proxy king, and Dongyue. Dongyue was defeated in a third military campaign in 111 BC and the former Minyue territory was annexed by the Han Empire.

Zhuang characters or Sawndip, are logograms derived from Chinese characters and used by the Zhuang people of Guangxi and Yunnan, China to write the Zhuang languages for more than one thousand years. The script is used not only by the Zhuang but also by the closely related Bouyei in Guizhou, China and Tay in Vietnam and Nùng, in Yunnan, China and Vietnam. Sawndip is a Zhuang word that means "immature characters". The Zhuang word for Chinese characters used in the Chinese language is sawgun ; gun is the Zhuang term for the Han Chinese. Even now, in traditional and less formal domains, Sawndip is more often used than alphabetical scripts.