In particle physics, the quantum yield (denoted Φ) of a radiation-induced process is the number of times a specific event occurs per photon absorbed by the system. [1]

In particle physics, the quantum yield (denoted Φ) of a radiation-induced process is the number of times a specific event occurs per photon absorbed by the system. [1]

The fluorescence quantum yield is defined as the ratio of the number of photons emitted to the number of photons absorbed. [2]

Fluorescence quantum yield is measured on a scale from 0 to 1.0, but is often represented as a percentage. A quantum yield of 1.0 (100%) describes a process where each photon absorbed results in a photon emitted. Substances with the largest quantum yields, such as rhodamines, display the brightest emissions; however, compounds with quantum yields of 0.10 are still considered quite fluorescent.

Quantum yield is defined by the fraction of excited state fluorophores that decay through fluorescence:

where

Non-radiative processes are excited state decay mechanisms other than photon emission, which include: Förster resonance energy transfer, internal conversion, external conversion, and intersystem crossing. Thus, the fluorescence quantum yield is affected if the rate of any non-radiative pathway changes. The quantum yield can be close to unity if the non-radiative decay rate is much smaller than the rate of radiative decay, that is kf > knr. [2]

Fluorescence quantum yields are measured by comparison to a standard of known quantum yield. [2] The quinine salt quinine sulfate in a sulfuric acid solution was regarded as the most common fluorescence standard, [3] however, a recent study revealed that the fluorescence quantum yield of this solution is strongly affected by the temperature, and should no longer be used as the standard solution. The quinine in 0.1M perchloric acid (Φ = 0.60) shows no temperature dependence up to 45 °C, therefore it can be considered as a reliable standard solution. [4]

| Compound | Solvent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quinine | 0.1 M HClO4 | 347.5 | 0.60 ± 0.02 |

| Fluorescein | 0.1 M NaOH | 496 | 0.95 ± 0.03 |

| Tryptophan | Water | 280 | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| Rhodamine 6G | Ethanol | 488 | 0.94 |

Experimentally, relative fluorescence quantum yields can be determined by measuring fluorescence of a fluorophore of known quantum yield with the same experimental parameters (excitation wavelength, slit widths, photomultiplier voltage etc.) as the substance in question. The quantum yield is then calculated by:

where

The subscript R denotes the respective values of the reference substance. [5] [6] The determination of fluorescence quantum yields in scattering media requires additional considerations and corrections. [7]

Förster resonance energy transfer efficiency (E) is the quantum yield of the energy-transfer transition, i.e. the probability of the energy-transfer event occurring per donor excitation event:

where

A fluorophore's environment can impact quantum yield, usually resulting from changes in the rates of non-radiative decay. [2] Many fluorophores used to label macromolecules are sensitive to solvent polarity. The class of 8-anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (ANS) probe molecules are essentially non-fluorescent when in aqueous solution, but become highly fluorescent in nonpolar solvents or when bound to proteins and membranes. The quantum yield of ANS is ~0.002 in aqueous buffer, but near 0.4 when bound to serum albumin.

The quantum yield of a photochemical reaction describes the number of molecules undergoing a photochemical event per absorbed photon: [1]

In a chemical photodegradation process, when a molecule dissociates after absorbing a light quantum, the quantum yield is the number of destroyed molecules divided by the number of photons absorbed by the system. Since not all photons are absorbed productively, the typical quantum yield will be less than 1.

Quantum yields greater than 1 are possible for photo-induced or radiation-induced chain reactions, in which a single photon may trigger a long chain of transformations. One example is the reaction of hydrogen with chlorine, in which as many as 106 molecules of hydrogen chloride can be formed per quantum of blue light absorbed. [10]

Quantum yields of photochemical reactions can be highly dependent on the structure, proximity and concentration of the reactive chromophores, the type of solvent environment as well as the wavelength of the incident light. Such effects can be studied with wavelength-tunable lasers and the resulting quantum yield data can help predict conversion and selectivity of photochemical reactions. [11]

In optical spectroscopy, the quantum yield is the probability that a given quantum state is formed from the system initially prepared in some other quantum state. For example, a singlet to triplet transition quantum yield is the fraction of molecules that, after being photoexcited into a singlet state, cross over to the triplet state.

Quantum yield is used in modeling photosynthesis: [12]

The Beer–Lambert law is commonly applied to chemical analysis measurements to determine the concentration of chemical species that absorb light. It is often referred to as Beer's law. In physics, the Bouguer–Lambert law is an empirical law which relates the extinction or attenuation of light to the properties of the material through which the light is travelling. It had its first use in astronomical extinction. The fundamental law of extinction is sometimes called the Beer–Bouguer–Lambert law or the Bouguer–Beer–Lambert law or merely the extinction law. The extinction law is also used in understanding attenuation in physical optics, for photons, neutrons, or rarefied gases. In mathematical physics, this law arises as a solution of the BGK equation.

In physics, the cross section is a measure of the probability that a specific process will take place in a collision of two particles. For example, the Rutherford cross-section is a measure of probability that an alpha particle will be deflected by a given angle during an interaction with an atomic nucleus. Cross section is typically denoted σ (sigma) and is expressed in units of area, more specifically in barns. In a way, it can be thought of as the size of the object that the excitation must hit in order for the process to occur, but more exactly, it is a parameter of a stochastic process.

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. Fluorescence involves no change in electron spin multiplicity and generally it immediately follows absorption; phosphorescence involves spin change and is delayed. Thus fluorescent materials generally cease to glow nearly immediately when the radiation source stops, while phosphorescent materials, which continue to emit light for some time after.

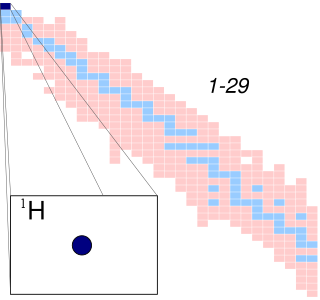

A hydrogen atom is an atom of the chemical element hydrogen. The electrically neutral atom contains a single positively charged proton and a single negatively charged electron bound to the nucleus by the Coulomb force. Atomic hydrogen constitutes about 75% of the baryonic mass of the universe.

In physics, optical depth or optical thickness is the natural logarithm of the ratio of incident to transmitted radiant power through a material. Thus, the larger the optical depth, the smaller the amount of transmitted radiant power through the material. Spectral optical depth or spectral optical thickness is the natural logarithm of the ratio of incident to transmitted spectral radiant power through a material. Optical depth is dimensionless, and in particular is not a length, though it is a monotonically increasing function of optical path length, and approaches zero as the path length approaches zero. The use of the term "optical density" for optical depth is discouraged.

An ideal gas is a theoretical gas composed of many randomly moving point particles that are not subject to interparticle interactions. The ideal gas concept is useful because it obeys the ideal gas law, a simplified equation of state, and is amenable to analysis under statistical mechanics. The requirement of zero interaction can often be relaxed if, for example, the interaction is perfectly elastic or regarded as point-like collisions.

In physics, Planck's law describes the spectral density of electromagnetic radiation emitted by a black body in thermal equilibrium at a given temperature T, when there is no net flow of matter or energy between the body and its environment.

In optics, a Fabry–Pérot interferometer (FPI) or etalon is an optical cavity made from two parallel reflecting surfaces. Optical waves can pass through the optical cavity only when they are in resonance with it. It is named after Charles Fabry and Alfred Perot, who developed the instrument in 1899. Etalon is from the French étalon, meaning "measuring gauge" or "standard".

Absorbance is defined as "the logarithm of the ratio of incident to transmitted radiant power through a sample ". Alternatively, for samples which scatter light, absorbance may be defined as "the negative logarithm of one minus absorptance, as measured on a uniform sample". The term is used in many technical areas to quantify the results of an experimental measurement. While the term has its origin in quantifying the absorption of light, it is often entangled with quantification of light which is “lost” to a detector system through other mechanisms. What these uses of the term tend to have in common is that they refer to a logarithm of the ratio of a quantity of light incident on a sample or material to that which is detected after the light has interacted with the sample.

In physics, the S-matrix or scattering matrix relates the initial state and the final state of a physical system undergoing a scattering process. It is used in quantum mechanics, scattering theory and quantum field theory (QFT).

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), fluorescence resonance energy transfer, resonance energy transfer (RET) or electronic energy transfer (EET) is a mechanism describing energy transfer between two light-sensitive molecules (chromophores). A donor chromophore, initially in its electronic excited state, may transfer energy to an acceptor chromophore through nonradiative dipole–dipole coupling. The efficiency of this energy transfer is inversely proportional to the sixth power of the distance between donor and acceptor, making FRET extremely sensitive to small changes in distance.

The term quantum efficiency (QE) may apply to incident photon to converted electron (IPCE) ratio of a photosensitive device, or it may refer to the TMR effect of a magnetic tunnel junction.

In particle physics, Yukawa's interaction or Yukawa coupling, named after Hideki Yukawa, is an interaction between particles according to the Yukawa potential. Specifically, it is a scalar field ϕ and a Dirac field ψ of the type

Fluorescence-lifetime imaging microscopy or FLIM is an imaging technique based on the differences in the exponential decay rate of the photon emission of a fluorophore from a sample. It can be used as an imaging technique in confocal microscopy, two-photon excitation microscopy, and multiphoton tomography.

In atomic physics, two-photon absorption (TPA or 2PA), also called two-photon excitation or non-linear absorption, is the simultaneous absorption of two photons of identical or different frequencies in order to excite an atom or a molecule from one state (usually the ground state), via a virtual energy level, to a higher energy, most commonly an excited electronic state. Absorption of two photons with different frequencies is called non-degenerate two-photon absorption. Since TPA depends on the simultaneous absorption of two photons, the probability of TPA is proportional to the photon dose (D), which is proportional to the square of the light intensity (D ∝ I2); thus it is a nonlinear optical process. The energy difference between the involved lower and upper states of the molecule is equal or smaller than the sum of the photon energies of the two photons absorbed. Two-photon absorption is a third-order process, with absorption cross section typically several orders of magnitude smaller than one-photon absorption cross section.

Fluorescence anisotropy or fluorescence polarization is the phenomenon where the light emitted by a fluorophore has unequal intensities along different axes of polarization. Early pioneers in the field include Aleksander Jablonski, Gregorio Weber, and Andreas Albrecht. The principles of fluorescence polarization and some applications of the method are presented in Lakowicz's book.

The theoretical and experimental justification for the Schrödinger equation motivates the discovery of the Schrödinger equation, the equation that describes the dynamics of nonrelativistic particles. The motivation uses photons, which are relativistic particles with dynamics described by Maxwell's equations, as an analogue for all types of particles.

Fluorescence interference contrast (FLIC) microscopy is a microscopic technique developed to achieve z-resolution on the nanometer scale.

Resonance fluorescence is the process in which a two-level atom system interacts with the quantum electromagnetic field if the field is driven at a frequency near to the natural frequency of the atom.

In atomic physics, non-degenerate two-photon absorption or two-color two-photon excitation is a type of two-photon absorption (TPA) where two photons with different energies are (almost) simultaneously absorbed by a molecule, promoting a molecular electronic transition from a lower energy state to a higher energy state. The sum of the energies of the two photons is equal to, or larger than, the total energy of the transition.