The Battle of Zama was fought in 202 BC in what is now Tunisia between a Roman army commanded by Scipio Africanus and a Carthaginian army commanded by Hannibal. The battle was part of the Second Punic War and resulted in such a severe defeat for the Carthaginians that they capitulated, while Hannibal was forced into exile. The Roman army of approximately 30,000 men was outnumbered by the Carthaginians who fielded either 40,000 or 50,000; the Romans were stronger in cavalry, but the Carthaginians had 80 war elephants.

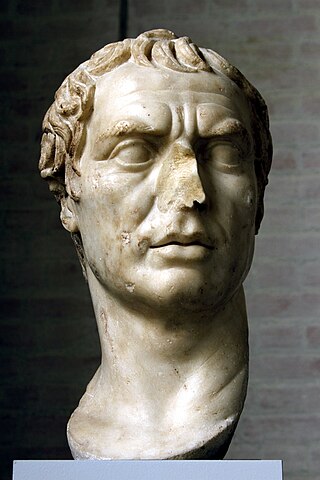

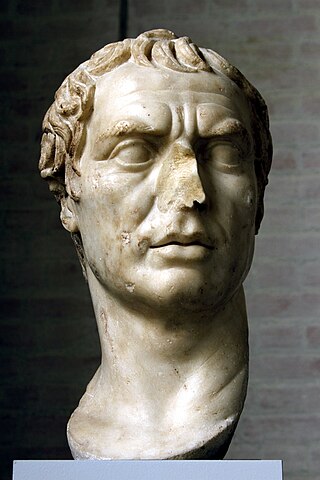

Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus was a general and statesman of the Roman Republic. He was the son of Publius Cornelius Scipio and the younger brother of Scipio Africanus. He was elected consul in 190 BC, and later that year led the Roman forces to victory at the Battle of Magnesia.

The siege of Carthage was the main engagement of the Third Punic War fought between Carthage and Rome. It consisted of the nearly-three-year siege of the Carthaginian capital, Carthage. In 149 BC, a large Roman army landed at Utica in North Africa. The Carthaginians hoped to appease the Romans, but despite the Carthaginians surrendering all of their weapons, the Romans pressed on to besiege the city of Carthage. The Roman campaign suffered repeated setbacks through 149 BC, only alleviated by Scipio Aemilianus, a middle-ranking officer, distinguishing himself several times. A new Roman commander took over in 148 BC, and fared equally badly. At the annual election of Roman magistrates in early 147 BC, the public support for Scipio was so great that the usual age restrictions were lifted to allow him to be appointed commander in Africa.

Quintus Baebius Tamphilus was a praetor of the Roman Republic who participated in negotiations with Hannibal attempting to forestall the Second Punic War.

In ancient Rome, a promagistrate was a person who was granted the power via prorogation to act in place of an ordinary magistrate in the field. This was normally pro consule or pro praetore, that is, in place of a consul or praetor, respectively. This was an expedient development, starting in 327 BC and becoming regular by 241 BC, that was meant to allow consuls and praetors to continue their activities in the field without disruption.

The Mercenary War, also known as the Truceless War, was a mutiny by troops that were employed by Carthage at the end of the First Punic War (264–241 BC), supported by uprisings of African settlements revolting against Carthaginian control. It lasted from 241 to late 238 or early 237 BC and ended with Carthage suppressing both the mutiny and the revolt.

Gaius Claudius Nero was a Roman general active during the Second Punic War against the invading Carthaginian force, led by Hannibal Barca. During a military career that began as legate in 214 BC, he was praetor in 212 BC, propraetor in 211 BC during the siege of Capua, before being sent to Spain that same year. He became consul in 207 BC.

Marcus Valerius Laevinus was a Roman consul and commander who rose to prominence during the Second Punic War and corresponding First Macedonian War. A member of the gens Valeria, an old patrician family believed to have migrated to Rome under the Sabine king T. Tatius, Laevinus played an integral role in the containment of the Macedonian threat.

The siege of Utica was a siege during the Second Punic War between the Roman Republic and Carthage in 204 BC. Roman general Scipio Africanus besieged Utica, intending to use it as a supply base for his campaign against Carthage in North Africa. He launched repeated and coordinated army-navy assaults on the city, all of which failed. The arrival of a large Carthaginian and Numidian relief army under Carthaginian general Hasdrubal Gisco and Numidian king Syphax in late autumn forced Scipio to break off the siege after 40 days and retreat to the coast.

Publius Sempronius C.f. Tuditanus was a Roman Republican consul and censor, best known for leading about 600 men to safety at Cannae in August, 216 BC and for the Treaty of Phoenice which ended the First Macedonian War, in 205 BC.

Manius Pomponius Matho was a Roman general who was elected consul for the year 233 BC with Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus. He was also the maternal grandfather of the general and statesman Scipio Africanus.

The battle of Utica was fought in 203 BC between a Roman army commanded by Publius Cornelius Scipio and the allied armies of Carthage and Numidia, commanded by Hasdrubal Gisgo and Syphax respectively. The battle was part of the Second Punic War and resulted in a heavy defeat for Carthage.

Quintus Minucius Rufus was a Roman senator and military commander.

Marcus Baebius Tamphilus was a consul of the Roman Republic in 181 BC along with P. Cornelius Cethegus. Baebius is credited with reform legislation pertaining to campaigns for political offices and electoral bribery (ambitus). The Lex Baebia was the first bribery law in Rome and had long-term impact on Roman administrative practices in the provinces.

Quintus Catius was an officer (legatus) of the Roman Republic during the Second Punic War.

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus was a Roman general and statesman, most notable as one of the main architects of Rome's victory against Carthage in the Second Punic War. Often regarded as one of the greatest military commanders and strategists of all time, his greatest military achievement was the defeat of Hannibal at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. This victory in Africa earned him the honorific epithet Africanus, literally meaning 'the African', but meant to be understood as a conqueror of Africa.

In Roman law, abrogatio is in general an annulment of a law or legal procedure.

The gens Matiena was a plebeian family at Rome. Members of this gens first appear in history in the time of the Second Punic War.

The gens Pleminia was a minor plebeian family at ancient Rome. The only member of this gens mentioned in history is Quintus Pleminius, infamous for his outrageous conduct at Locri during the Second Punic War. Other Pleminii are known from inscriptions.

The Battle of Oroscopa was fought between a Carthaginian army of more than 30,000 men commanded by the general Hasdrubal and a Numidian force of unknown size under its king, Masinissa. It took place in late 151 BC near the ancient town of Oroscopa in what is now north western Tunisia. The battle resulted in a heavy Carthaginian defeat.