Scottish coup d'état

Ruthven Castle

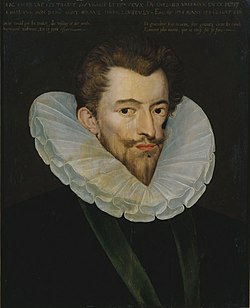

In July 1582 the discontented lords made a bond to one another in their enterprise to displace Catholic influences around the young king. Their party became known as the "Lords Enterprisers", and their opponents were the King's favourite, the Frenchman Esmé Stewart, 1st Duke of Lennox, and James Stewart, Earl of Arran, who shared control of the government. James VI was seized while he was hunting near the castle of Ruthven in Perthshire on 22 (or 23) August. [4] Some sources, including the letters of Robert Bowes, an English diplomat sent to Scotland after the event, state the King was captured at Ruthven Castle on 23 August. The Ruthven lords presented the King with a lengthy "supplication" to explain the motives of their surprise action, dated 23 August. [5]

The 17th-century historian David Calderwood named the Ruthven Raiders as the Earls of Mar and Gowrie, the Master of Glamis, the Laird of Easter-Wemyss, Lewis Bellenden, Lord Boyd, Lord Lindsay, the Abbot of Dunfermline, David Erskine, Commendator of Dryburgh, the Abbot of Paisley, the Prior of Pittenween and the Constable of Dundee. [6]

It was said that James VI started to cry. [7] The Master of Glamis is reported to have said, "Better bairns greet than bearded men". [8] ("Greet" is a Scots word meaning "weep, mourn." [9] )

To prevent a rescue attempt by the Duke of Lennox's soldiers, the Earl of Mar stationed an armed force at Kinross to break their march northward. The Earl of Arran's brother, William Stewart, reached Ruthven, fought the raiders, lost two fingers and was captured. Arran himself arrived and was captured. [10]

The king was held and controlled by the Ruthven Lords for ten months, until managing to escape on 27 June 1583. [1] He was moved around a number of houses. He was taken to Perth the next day, where the Earl of Gowrie had a large townhouse, as provost of the town. [11] David Moysie wrote that the lords had given him their "supplication" at Perth, and James then was taken to Stirling Castle at the end of August. At Stirling, the Ruthven party was swelled by Francis Stewart, Earl of Bothwell; the Earl of Glencairn; and Laurence, Master of Oliphant, and their retainers had now grown to 400. [12] The English diplomats Robert Bowes and George Carey came to Stirling on 14 September and Mary's supporter George Douglas was interrogated about secret French correspondence. [13] In October 1582, James was at Holyrood Palace, in Edinburgh. [14]

Ruthven Castle's name was officially changed to Huntingtower in 1600, after the Gowrie House conspiracy. The castle is maintained and opened to the public by Historic Environment Scotland.

Historical sources

Copies of relevant papers, such as the Lords' "supplication" of 23 August 1582 and Lennox's protest, "D'Obany's petition", were given by John Colville to Robert Bowes and sent to England, where they remain in the Public Record Office. [15]

Opponents of Regime

The Earl of Gowrie remained at the head of the government and was assisted by figures like the Master of Glamis. The king's favourite, Esmé Stewart, Duke of Lennox, the main politician who was targeted by the coup, was sent to Dumbarton Castle and was forced into exile in France after he had lingered at Rothesay Castle on the Island of Bute, and died in Paris in May 1583. Another prominent politician, the recently ennobled James Stewart, Earl of Arran, was imprisoned at Dupplin, Stirling, Ruthven (Huntingtower) and then confined at his own Kinneil House.

Among the rest of the nobility, the Ruthven regime was opposed by the Earls of Huntly, Crawford, Morton (Maxwell) and Sutherland and the Lords Livingston, Seton, Ogilvy, Ochiltree and Doune, all of whom were reported to support Arran and Lennox.

Policy

The resultant Gowrie regime favoured what has been described as an ultra-Protestant regime and was approved by the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland as the 'late act of the Scottish reformation'. [16] It was approved by influential ministers of the Kirk of Scotland from the pulpit. These churchmen were called "Melvillians" after their spokesman, Andrew Melville. [17] The noble leaders of the regime also included those who were "discomfited" by the fall of James Douglas, Regent Morton in 1581, and the Douglas family, which had been exiled in England, were re-instated on 28 September 1582.

The coup was also prompted by an urge to curb excessive spending at court. Because of its extravagance, the Earl of Gowrie as Lord High Treasurer of Scotland was owed £48,000. [18] The debt was never repaid. [19] A number of cost-saving measures for the royal household were proposed by Gowrie and his exchequer colleagues. [20] They were described as "havand respect to the order of the hous of your hieness goudsire King James the fifth of worthie memorie and to the possibilitie[ sic ] of your majesties present rents", a reference to the alleged thriftiness of James V. [21]

Lennox seems to have made himself particularly unpopular by using his office of Chamberlain to profit from merchant trade in the Scottish towns and burghs. The Ruthven Regime ordered him to leave Scotland. Lennox delayed his exile unto 22 December, when he sailed for France and never returned. [22]

Response in England

Queen Elizabeth I was pleased with events and sent £1000 in September 1582 to Robert Bowes, a payment declared as the wages of the King's Guard. [23] In response, the opponents of the Ruthven Regime, the Earls of Huntley, Argyll, Atholl, Crawford, Montrose, Arran, Lennox and Sutherland, wrote a letter from Dunkeld, near Atholl's Blair Castle, to the town of Edinburgh and described this force, funded by England, as 400 men-of-est raised to convey James VI to their "auld enemies" in England. They urged the townspeople of Edinburgh to arm themselves and to seize James, who was at Holyroodhouse, on their behalf. The people of Edinburgh did not follow up on the suggestion. [24]

The reaction of Francis Walsingham was more circumspect. He wrote to the Earl of Shrewsbury, the keeper of Mary, Queen of Scots, with news of progress in Scotland on 26 September 1582. Walsingham thought that "thinges stand not yet in so good termes as were to be wished". He found James's own letters, and his speech in favour of the Duke of Lennox made at Stirling on 14 September, to demonstrate 'of what rare towardliness that yonge prince is, and howe dangerous an enemye therefore he would prove unto England yf he should happen to runne to any other coorse". [25]

In September, Mary sent Jean Champhuon, sieur du Ruisseau, a brother-in-law of her secretary, Claude Nau, to the Duke of Guise to discuss possible plans. They included taking James VI to France and invading Scotland with 600 musketeers, possibly with papal funding. Mary envisaged a landing at Dumbarton Castle and the capture of Blackness Castle and Stirling Castle. [26]

French reaction and English diplomacy

Catherine de' Medici, the French queen mother, wrote to the French ambassador in London, Michel de Castelnau, with her concerns over the capture of James and the exile of Lennox. [27] Elizabeth I was told that Castelnau had secretly conveyed letters to Mary, Queen of Scots, and to her supporters in Scotland. Walsingham asked the ambassador in France, Henry Cobham, to advise King Henry III of France and Catherine de' Medici of the situation and that Castelnau should be more circumspect in the handling of Mary's letters. Elizabeth had no wish to foment further disquiet in Scotland after the recent disturbances. [28]

Requests for funding

Colonel William Stewart was sent as ambassador by the Regime to England in April 1583 to ask for £10,000 and yearly £5000 as an income from the English lands of Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox, and for the ratification and renewal of the 1560 Treaty of Edinburgh. Stewart was to enquire discreetly of the succession to the English throne. [29] Robert Bowes, the English diplomat, stayed in Edinburgh and followed events. As it seemed opportune, he was instructed by Walsingham to seek out the casket letters, which had been used to incriminate Queen Mary in 1568, but the Earl of Gowrie refused to hand them over.

French embassy

Gowrie was also courted by France and received in February 1583 an offer of a yearly pension of 100,000 crowns for the state, 2000 crowns personally and a lump sum of 10,000 crowns. Two French ambassadors, Bertrand de Salignac de la Mothe-Fénelon and François de Rocherolles, Sieur de Maineville, hoped to secure French influence over James VIs choice of bride. [30] James gave the French ambassadors an audience in the presence of William Davidson, an English diplomat who would later deliver Mary's death warrant. The ambassadors intended to build a pro-French faction and may have offered French pensions to sympathetic nobles. Maineville remained in Scotland until May 1583. His presence and unpopularity divided the Ruthven lords and weakened their support. [31]

Failure of Regime

Gowrie's regime was ineffectually supported by Elizabeth I and Walsingham. After ten months, James gained his freedom at St Andrews in July 1583. He first stayed at the New Inns of St Andrews but was persuaded to sleep in St Andrews Castle. The faction against the Regime was there in strength, the Lords Enterprisers were dismissed from court and a number of their followers who were salaried court servants were removed from office. [32]

King James went to Stirling and Falkland Palace. Lennox's messenger George Douglas was interrogated at Stirling. [33] James joined Arran for a banquet at Kinneil House on 13 November and returned to Edinburgh. The Earl of Arran gained a brief ascendancy in Scottish politics. The Earl of Gowrie was pardoned, but kept plotting and was later beheaded for high treason. In November 1585, however, Arran himself was removed from public affairs.

Walsingham in Scotland

As Elizabeth was displeased by the fall of the Regime, Walsingham was sent as ambassador to Scotland in September 1583. [34] He spoke to James VI at Perth and was convinced that Mary's influence was dominant in Scotland and working to the young James's confusion. Walshingham wrote to Elizabeth that Mary, "though she cannot live many years", would see his overthrow.

James had not enjoyed the Ruthven government. Walsingham found him unable to take his complaints seriously. James laughed at Walsingham, "falling into a distemperture". He told Walshingham of being an "absolute King" who would order his subjects as he would "best lyke himself". [35]

Arran and the Earl of Crawford hired Kate the Witch to disrupt Walsingham's visit with £6 and a length of plaid cloth. She stood outside the royal palaces and complained about the amity with England, the kirk and the nobility. [36]