Related Research Articles

The Kingdom of the East Saxons, referred to as the Kingdom of Essex, was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Middlesex, much of Hertfordshire and west Kent. The last king of Essex was Sigered of Essex, who in 825 ceded the kingdom to Ecgberht, King of Wessex.

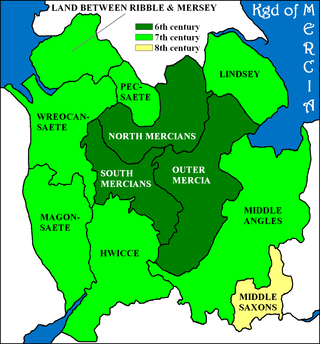

Mercia was one of the three notable Anglic kingdoms founded after Sub-Roman Britain was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred around the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlands of England.

Ecgberht, also spelled Egbert, Ecgbert, Ecgbriht, Ecgbeorht, and Ecbert, was King of Wessex from 802 until his death in 839. His father was King Ealhmund of Kent. In the 780s, Ecgberht was forced into exile to Charlemagne's court in the Frankish Empire by the kings Offa of Mercia and Beorhtric of Wessex, but on Beorhtric's death in 802, Ecgberht returned and took the throne.

Ine, also rendered Ini or Ina, was King of Wessex from 689 to 726. At Ine's accession, his kingdom dominated much of southern England. However, he was unable to retain the territorial gains of his predecessor, Cædwalla, who had expanded West Saxon territory substantially. By the end of Ine's reign, the kingdoms of Kent, Sussex, and Essex were no longer under West Saxon sway; however, Ine maintained control of what is now Hampshire, and consolidated and extended Wessex's territory in the western peninsula.

Anna was king of East Anglia from the early 640s until his death. He was a member of the Wuffingas family, the ruling dynasty of the East Angles, and one of the three sons of Eni who ruled the kingdom of East Anglia, succeeding some time after Ecgric was killed in battle by Penda of Mercia. Anna was praised by Bede for his devotion to Christianity and was renowned for the saintliness of his family: his son Jurmin and all his daughters – Seaxburh, Æthelthryth, Æthelburh and possibly a fourth, Wihtburh – were canonised.

The hide was an English unit of land measurement originally intended to represent the amount of land sufficient to support a household. It was traditionally taken to be 120 acres , but was in fact a measure of value and tax assessment, including obligations for food-rent, maintenance and repair of bridges and fortifications, manpower for the army, and (eventually) the geld land tax. The hide's method of calculation is now obscure: different properties with the same hidage could vary greatly in extent even in the same county. Following the Norman Conquest of England, the hidage assessments were recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086, and there was a tendency for land producing £1 of income per year to be assessed at 1 hide. The Norman kings continued to use the unit for their tax assessments until the end of the 12th century.

The Rodings are a group of eight villages in the upper part of the River Roding and the west of Essex, England, the largest group in the country to bear a common name. The Rodings do not lie within a single district in the county; they are arranged around the tripoint of the administrative areas of Chelmsford, Uttlesford and Epping Forest. An alternative arcane name, linked to the Middle English Essex dialect, was The Roothings.

The Tribal Hidage is a list of thirty-five tribes that was compiled in Anglo-Saxon England some time between the 7th and 9th centuries. It includes a number of independent kingdoms and other smaller territories, and assigns a number of hides to each one. The list is headed by Mercia and consists almost exclusively of peoples who lived south of the Humber estuary and territories that surrounded the Mercian kingdom, some of which have never been satisfactorily identified by scholars. The value of 100,000 hides for Wessex is by far the largest: it has been suggested that this was a deliberate exaggeration.

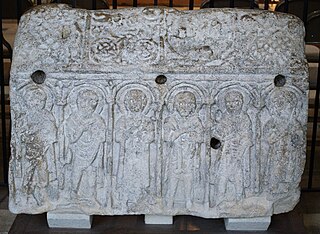

Medeshamstede was the name of Peterborough in the Anglo-Saxon period. It was the site of a monastery founded around the middle of the 7th century, which was an important feature in the kingdom of Mercia from the outset. Little is known of its founder and first abbot, Sexwulf, though he was himself an important figure, and later became bishop of Mercia. Medeshamstede soon acquired a string of daughter churches, and was a centre for an Anglo-Saxon sculptural style.

The Basingas were an Old English tribe, whose territory in the Loddon Valley formed a regio or administrative subdivision of the early Kingdom of Wessex. Their leader, Basa, gave the tribe its name which survives in the names of Old Basing and Basingstoke, both in Hampshire.

The Pecsætan, also called Peaklanders or Peakrills in modern English, were an Anglo-Saxon tribe who inhabited the central and northern parts of the Peak District area in England.

Edward the Elder was King of the Anglo-Saxons from 899 until his death in 924. He was the elder son of Alfred the Great and his wife Ealhswith. When Edward succeeded to the throne, he had to defeat a challenge from his cousin Æthelwold, who had a strong claim to the throne as the son of Alfred's elder brother and predecessor, Æthelred I.

The Middle Angles were an important ethnic or cultural group within the larger kingdom of Mercia in England in the Anglo-Saxon period.

The Kingdom of the East Angles, today known as the Kingdom of East Anglia, was a small independent kingdom of the Angles comprising what are now the English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk and perhaps the eastern part of the Fens. The kingdom formed in the 6th century in the wake of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. It was ruled by the Wuffingas dynasty in the 7th and 8th centuries, but fell to Mercia in 794, and was conquered by the Danes in 869, to form part of the Danelaw. It was conquered by Edward the Elder and incorporated into the Kingdom of England in 918.

The Beormingas were a tribe or clan in Anglo-Saxon England, whose territory possibly formed a regio or early administrative subdivision of the Kingdom of Mercia. The name literally means "Beorma's people" in Old English, and Beorma is likely to have been either the leader of the group during its settlement in Britain or a real or legendary tribal ancestor. The name of the tribe is recorded in the place name Birmingham, which means "home of the Beormingas".

The Mercian Supremacy was the period of Anglo-Saxon history between c. 716 and c. 825, when the kingdom of Mercia dominated the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy in England. Sir Frank Stenton apparently coined the phrase, arguing that Offa of Mercia, who ruled 757–796, effectively achieved the unification of England south of the Humber estuary. Scholastic opinion on the relationship between the kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia at this time remains divided.

A royal vill, royal tun or villa regalis was the central settlement of a rural territory in Anglo Saxon England, which would be visited by the King and members of the royal household on regular circuits of their kingdoms. The royal vill was the centre for the administration of a subdivision of a kingdom, and the location where the subdivision would support the royal household through the provision of food rent. Royal vills have been identified as the centres of the regiones of the early Anglo-Saxon period, and of the smaller multiple estates into which regiones were gradually divided by the 8th century.

Food render or food rent was a form of tax in kind levied in Anglo-Saxon England, consisting of essential foodstuffs provided by territories such as regiones, multiple estates or hundreds to kings and other members of royal households at a territory's royal vill.

The Brahhingas or Brahingas were a tribe or clan of Anglo-Saxon England whose territory was centred on the settlement of Braughing in modern-day Hertfordshire. The name of the tribe means "the people of Brahha", with Brahha likely to have been either a leader of the tribe or a real or mythical ancestor.

The Waeclingas were a tribe or clan of Anglo-Saxon England. Their territory or regio was based in the modern city of St Albans, whose name is recorded as Wæclingaceaster in the writings of Bede in the early 8th century, and in an early 10th century Anglo-Saxon charter. Before the territory came under Mercian control around 660 it may have formed part of the province of the Middle Saxons, or it may have fallen under the influence of the Kingdom of Essex – neither is certain.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Stenton 1971, p. 293.

- ↑ Rippon 2012, pp. 188, 190.

- 1 2 Yorke 1995, p. 39.

- ↑ Faith 1999, pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Faith 1999, p. 9.

- ↑ Faith 1999, pp. 5–8.

- ↑ Faith 1999, p. 8.

- ↑ Rippon 2012, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 Yorke 1995, p. 40.

- ↑ Yorke 1995, pp. 40, 41.

- ↑ Bailey 1989, p. 121.

- ↑ Williamson 2013, p. 83.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, p. 295.

- 1 2 Thornton 2009, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 Yorke 1995, p. 42.

- ↑ Williamson 2013, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Yorke 1995, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Williamson 2013, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Rippon 2012, p. 191.

- 1 2 Campbell 2008, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 Bassett 1989, p. 19.

- ↑ Campbell 2008, p. 40.

- 1 2 Faith 1999, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Bassett 1989, p. 21.

- ↑ Campbell 2008, pp. 32, 35.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards 1989, p. 28.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards 1989, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Bassett 1989, p. 17.

- ↑ Bassett 1989, p. 20.

- ↑ Bassett 1989, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, p. 503.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, p. 504.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, p. 300.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, pp. 300–301.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, p. 301.