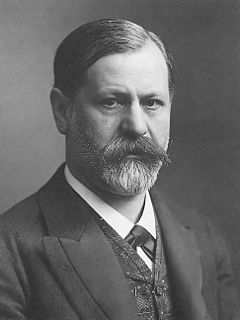

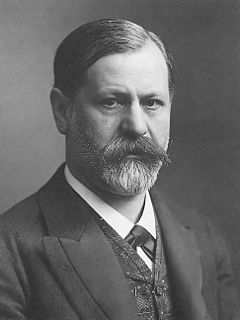

Psychoanalysis is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques used to study the unconscious mind, which together form a method of treatment for mental disorders. The discipline was established in the early 1890s by Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud, who retained the term psychoanalysis for his own school of thought. Freud's work stems partly from the clinical work of Josef Breuer and others. Psychoanalysis was later developed in different directions, mostly by students of Freud, such as Alfred Adler and his collaborator, Carl Gustav Jung, as well as by neo-Freudian thinkers, such as Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, and Harry Stack Sullivan.

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient and a psychoanalyst.

The unconscious mind consists of the processes in the mind which occur automatically and are not available to introspection and include thought processes, memories, interests and motivations.

Psychoanalytic theory is the theory of personality organization and the dynamics of personality development that guides psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology. First laid out by Sigmund Freud in the late 19th century, psychoanalytic theory has undergone many refinements since his work. Psychoanalytic theory came to full prominence in the last third of the twentieth century as part of the flow of critical discourse regarding psychological treatments after the 1960s, long after Freud's death in 1939. Freud had ceased his analysis of the brain and his physiological studies and shifted his focus to the study of the mind and the related psychological attributes making up the mind, and on treatment using free association and the phenomena of transference. His study emphasized the recognition of childhood events that could influence the mental functioning of adults. His examination of the genetic and then the developmental aspects gave the psychoanalytic theory its characteristics. Starting with his publication of The Interpretation of Dreams in 1899, his theories began to gain prominence.

A Freudian slip, also called parapraxis, is an error in speech, memory, or physical action that occurs due to the interference of an unconscious subdued wish or internal train of thought. The concept is part of classical psychoanalysis. Classical examples involve slips of the tongue, but psychoanalytic theory also embraces misreadings, mishearings, mistypings, temporary forgettings, and the mislaying and losing of objects.

Neo-Freudianism is a psychoanalytic approach derived from the influence of Sigmund Freud but extending his theories towards typically social or cultural aspects of psychoanalysis over the biological.

Nancy Julia Chodorow is an American sociologist and professor. She describes herself as a humanistic psychoanalytic sociologist and psychoanalytic feminist. Throughout her career, she has been influenced by psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Karen Horney, as well as feminist theorists Beatrice Whiting and Phillip Slater. She is a member of the International Psychoanalytical Association, and often speaks at its congresses. She began as a professor at Wellesley College in 1973, a year later she began at the University of California, Santa Cruz until 1986. She then went on to spend many years as a professor in the departments of sociology and clinical psychology at the University of California, Berkeley until her retirement in 2005. Later, she began her career teaching psychiatry at Harvard Medical School/Cambridge Health Alliance. Chodorow is often described as a leader in feminist thought, especially in the realms of psychoanalysis and psychology.

Ego psychology is a school of psychoanalysis rooted in Sigmund Freud's structural id-ego-superego model of the mind.

Otto Fenichel was a psychoanalyst of the so-called "second generation".

Resistance, in psychoanalysis, refers to oppositional behavior when an individual's unconscious defenses of the ego are threatened by an external source. Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalytic theory, developed his concept of resistance as he worked with patients who suddenly developed uncooperative behaviors during sessions of talk therapy. He reasoned that an individual that is suffering from a psychological affliction, which Freud believed to be derived from the presence of suppressed illicit or unwanted thoughts, may inadvertently attempt to impede any attempt to confront a subconsciously perceived threat. This would be for the purpose of inhibiting the revelation of any repressed information from within the unconscious mind.

Freud's seduction theory was a hypothesis posited in the mid-1890s by Sigmund Freud that he believed provided the solution to the problem of the origins of hysteria and obsessional neurosis. According to the theory, a repressed memory of an early childhood sexual abuse or molestation experience was the essential precondition for hysterical or obsessional symptoms, with the addition of an active sexual experience up to the age of eight for the latter.

Psychoanalytic dream interpretation is a subdivision of dream interpretation as well as a subdivision of psychoanalysis pioneered by Sigmund Freud in the early twentieth century. Psychoanalytic dream interpretation is the process of explaining the meaning of the way the unconscious thoughts and emotions are processed in the mind during sleep.

Metapsychology is that aspect of any psychological theory which refers to the structure of the theory itself rather than to the entity it describes. The psychology is about the psyche; the metapsychology is about the psychology. The term is used mostly in discourse about psychoanalysis, the psychology developed by Sigmund Freud, which was at its time regarded as a branch of science, or, more recently, as a hermeneutics of understanding. Interest on the possible scientific status of psychoanalysis has been renewed in the emerging discipline of neuropsychoanalysis, whose major exemplar is Mark Solms. The hermeneutic vision of psychoanalysis is the focus of influential works by Donna Orange.

The Oedipus complex is a concept of psychoanalytic theory. Sigmund Freud introduced the concept in his Interpretation of Dreams (1899) and coined the expression in his A Special Type of Choice of Object made by Men (1910). The positive Oedipus complex refers to a child's unconscious sexual desire for the opposite-sex parent and hatred for the same-sex parent. The negative Oedipus complex refers to a child's unconscious sexual desire for the same-sex parent and hatred for the opposite-sex parent. Freud considered that the child's identification with the same-sex parent is the successful outcome of the complex and that unsuccessful outcome of the complex might lead to neurosis, pedophilia, and homosexuality.

In Freudian dream analysis, content is both the manifest and latent content in a dream, that is, the dream itself as it is remembered, and the hidden meaning of the dream.

The Assault on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory is a book by the former psychoanalyst Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, in which the author argues that Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, deliberately suppressed his early hypothesis, known as the seduction theory, that hysteria is caused by sexual abuse during infancy, because he refused to believe that children are the victims of sexual violence and abuse within their own families. Masson reached this conclusion while he had access to some of Freud's unpublished letters as projects director of the Sigmund Freud Archives. The Assault on Truth was first published in 1984 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux; several revised editions have since been published.

The Foundations of Psychoanalysis: A Philosophical Critique is a 1984 book by the philosopher Adolf Grünbaum, in which the author offers a philosophical critique of the work of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. The book was first published in the United States by the University of California Press. Grünbaum evaluates the status of psychoanalysis as a natural science, criticizes the method of free association and Freud's theory of dreams, and discusses the psychoanalytic theory of paranoia. He argues that Freud, in his efforts to defend psychoanalysis as a method of clinical investigation, employed an argument that Grünbaum refers to as the "Tally Argument"; according to Grünbaum, it rests on the premises that only psychoanalysis can provide patients with correct insight into the unconscious pathogens of their psychoneuroses and that such insight is necessary for successful treatment of neurotic patients. Grünbaum argues that the argument suffers from major problems. Grünbaum also criticizes the views of psychoanalysis put forward by other philosophers, including the hermeneutic interpretations propounded by Jürgen Habermas and Paul Ricœur, as well as Karl Popper's position that psychoanalytic propositions cannot be disconfirmed and that psychoanalysis is therefore a pseudoscience.

Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation is a 1965 book about Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, by the French philosopher Paul Ricœur. In Freud and Philosophy, Ricœur interprets Freud's work in terms of hermeneutics, the theory of the rules that govern the interpretation of a particular text, and discusses phenomenology, a school of philosophy founded by Edmund Husserl. He addresses questions such as the nature of interpretation in psychoanalysis, the understanding of human nature to which it leads, and the relationship between Freud's interpretation of culture and other interpretations. The book was first published in France by Éditions du Seuil, and in the United States by Yale University Press.

The Memory Wars: Freud's Legacy in Dispute is a 1995 book that reprints articles by the critic Frederick Crews critical of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, and recovered-memory therapy. It also reprints letters from Harold P. Blum, Marcia Cavell, Morris Eagle, Matthew Erdelyi, Allen Esterson, Robert R. Holt, James Hopkins, Lester Luborsky, David D. Olds, Mortimer Ostow, Bernard L. Pacella, Herbert S. Peyser, Charlotte Krause Prozan, Theresa Reid, James L. Rice, Jean Schimek, and Marian Tolpin.

Sigmund Freud is considered to be the founder of the psychodynamic approach to psychology, which looks to unconscious drives to explain human behavior. Freud believed that the mind is responsible for both conscious and unconscious decisions that it makes on the basis of psychological drives. The id, ego, and super-ego are three aspects of the mind Freud believed to comprise a person's personality. Freud believed people are "simply actors in the drama of [their] own minds, pushed by desire, pulled by coincidence. Underneath the surface, our personalities represent the power struggle going on deep within us".