Related Research Articles

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a form of psychotherapy that aims to reduce symptoms of various mental health conditions, primarily depression, PTSD and anxiety disorders. Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on challenging and changing cognitive distortions and their associated behaviors to improve emotional regulation and develop personal coping strategies that target solving current problems. Though it was originally designed as an approach to treat depression, CBT is often prescribed for the evidence-informed treatment of many mental health and other conditions, including anxiety, substance use disorders, marital problems, ADHD, and eating disorders. CBT includes a number of cognitive or behavioral psychotherapies that treat defined psychopathologies using evidence-based techniques and strategies.

In psychoanalytic theory, defence mechanisms are unconscious psychological processes that protect the self from anxiety-producing thoughts and feelings related to internal conflicts and external stressors.

Perfectionism, in psychology, is a broad personality trait characterized by a person's concern with striving for flawlessness and perfection and is accompanied by critical self-evaluations and concerns regarding others' evaluations. It is best conceptualized as a multidimensional and multilayered personality characteristic, and initially some psychologists thought that there were many positive and negative aspects.

Acceptance and commitment therapy is a form of psychotherapy, as well as a branch of clinical behavior analysis. It is an empirically-based psychological intervention that uses acceptance and mindfulness strategies along with commitment and behavior-change strategies to increase psychological flexibility.

Exposure therapy is a technique in behavior therapy to treat anxiety disorders. Exposure therapy involves exposing the patient to the anxiety source or its context. Doing so is thought to help them overcome their anxiety or distress. Numerous studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in the treatment of disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and specific phobias.

In psychology, self-compassion is extending compassion to one's self in instances of perceived inadequacy, failure, or general suffering. American psychologist Kristin Neff has defined self-compassion as being composed of three main elements – self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness.

Social anxiety is the anxiety and fear specifically linked to being in social settings. Some categories of disorders associated with social anxiety include anxiety disorders, mood disorders, autism spectrum disorders, eating disorders, and substance use disorders. Individuals with higher levels of social anxiety often avert their gazes, show fewer facial expressions, and show difficulty with initiating and maintaining a conversation. Social anxiety commonly manifests itself in the teenage years and can be persistent throughout life; however, people who experience problems in their daily functioning for an extended period of time can develop social anxiety disorder. Trait social anxiety, the stable tendency to experience this anxiety, can be distinguished from state anxiety, the momentary response to a particular social stimulus. Half of the individuals with any social fears meet the criteria for social anxiety disorder. Age, culture, and gender impact the severity of this disorder. The function of social anxiety is to increase arousal and attention to social interactions, inhibit unwanted social behavior, and motivate preparation for future social situations.

The self-regulation of emotion or emotion regulation is the ability to respond to the ongoing demands of experience with the range of emotions in a manner that is socially tolerable and sufficiently flexible to permit spontaneous reactions as well as the ability to delay spontaneous reactions as needed. It can also be defined as extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions. The self-regulation of emotion belongs to the broader set of emotion regulation processes, which includes both the regulation of one's own feelings and the regulation of other people's feelings.

Behavioral theories of depression explain the etiology of depression based on the behavioural sciences; adherents promote the use of behavioral therapies for depression.

Rumination is the focused attention on the symptoms of one's mental distress. In 1998, Nolen-Hoeksema proposed the Response Styles Theory, which is the most widely used conceptualization model of rumination. However, other theories have proposed different definitions for rumination. For example, in the Goal Progress Theory, rumination is conceptualized not as a reaction to a mood state, but as a "response to failure to progress satisfactorily towards a goal". According to multiple studies, rumination is a mechanism that develops and sustains psychopathology conditions such as anxiety, depression, and other negative mental disorders. There are some defined models of rumination, mostly interpreted by the measurement tools. Multiple tools exist to measure ruminative thoughts. Treatments specifically addressing ruminative thought patterns are still in the early stages of development.

In psychology, avoidance coping is a coping mechanism and form of experiential avoidance. It is characterized by a person's efforts, conscious or unconscious, to avoid dealing with a stressor in order to protect oneself from the difficulties the stressor presents. Avoidance coping can lead to substance abuse, social withdrawal, and other forms of escapism. High levels of avoidance behaviors may lead to a diagnosis of avoidant personality disorder, though not everyone who displays such behaviors meets the definition of having this disorder. Avoidance coping is also a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder and related to symptoms of depression and anxiety. Additionally, avoidance coping is part of the approach-avoidance conflict theory introduced by psychologist Kurt Lewin.

Flexibility is a personality trait that describes the extent to which a person can cope with changes in circumstances and think about problems and tasks in novel, creative ways. This trait comes into play when stressors or unexpected events occur, requiring that a person change their stance, outlook, or commitment.

Driving phobia, driving anxiety, vehophobia, amaxophobia or driving-related fear (DRF) is a pathological fear of driving. It is an intense, persistent fear of participating in car traffic that affects a person's lifestyle, including aspects such as an inability to participate in certain jobs due to the pathological avoidance of driving. The fear of driving may be triggered by specific driving situations, such as expressway driving or dense traffic. Driving anxiety can range from a mild cautious concern to a phobia.

Fear of negative evaluation (FNE), or fear of failure, also known as atychiphobia, is a psychological construct reflecting "apprehension about others' evaluations, distress over negative evaluations by others, and the expectation that others would evaluate one negatively". The construct and a psychological test to measure it were defined by David Watson and Ronald Friend in 1969. FNE is related to specific personality dimensions, such as anxiousness, submissiveness, and social avoidance. People who score high on the FNE scale are highly concerned with seeking social approval or avoiding disapproval by others and may tend to avoid situations where they have to undergo evaluations. High FNE subjects are also more responsive to situational factors. This has been associated with conformity, pro-social behavior, and social anxiety.

Cognitive emotional behavioral therapy (CEBT) is an extended version of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) aimed at helping individuals to evaluate the basis of their emotional distress and thus reduce the need for associated dysfunctional coping behaviors. This psychotherapeutic intervention draws on a range of models and techniques including dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), mindfulness meditation, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and experiential exercises.

Interpersonal emotion regulation is the process of changing the emotional experience of one's self or another person through social interaction. It encompasses both intrinsic emotion regulation, in which one attempts to alter their own feelings by recruiting social resources, as well as extrinsic emotion regulation, in which one deliberately attempts to alter the trajectory of other people's feelings.

Emotional abandonment is a subjective emotional state in which people feel undesired, left behind, insecure, or discarded. People experiencing emotional abandonment may feel at a loss. They may feel like they have been cut off from a crucial source of sustenance or feel withdrawn, either suddenly or through a process of erosion. Emotional abandonment can manifest through loss or separation from a loved one.

Safety behaviors are coping behaviors used to reduce anxiety and fear when the user feels threatened. An example of a safety behavior in social anxiety is to think of excuses to escape a potentially uncomfortable situation. These safety behaviors, although useful for reducing anxiety in the short term, might become maladaptive over the long term by prolonging anxiety and fear of nonthreatening situations. This problem is commonly experienced in anxiety disorders. Treatments such as exposure and response prevention focus on eliminating safety behaviors due to the detrimental role safety behaviors have in mental disorders. There is a disputed claim that safety behaviors can be beneficial to use during the early stages of treatment.

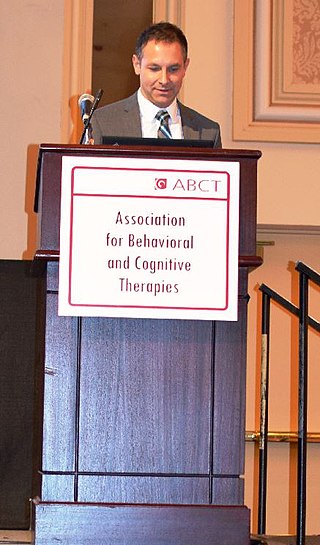

Jonathan Stuart Abramowitz is an American clinical psychologist and Professor in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH). He is an expert on obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and anxiety disorders whose work is highly cited. He maintains a research lab and currently serves as the Director of the UNC-CH Clinical Psychology PhD Program. Abramowitz approaches the understanding and treatment of psychological problems from a cognitive-behavioral perspective.

Distress tolerance is an emerging construct in psychology that has been conceptualized in several different ways. Broadly, however, it refers to an individual's "perceived capacity to withstand negative emotional and/or other aversive states, and the behavioral act of withstanding distressing internal states elicited by some type of stressor." Some definitions of distress tolerance have also specified that the endurance of these negative events occur in contexts in which methods to escape the distressor exist.

References

- Chawla, Neharika; Ostafin, Brian (2007). "Experiential avoidance as a functional dimensional approach to psychopathology: An empirical review". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 63 (9): 871–90. doi:10.1002/jclp.20400. PMID 17674402.

- Gámez, Wakiza; Chmielewski, Michael; Kotov, Roman; Ruggero, Camilo; Watson, David (2011). "Development of a measure of experiential avoidance: The Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire". Psychological Assessment. 23 (3): 692–713. doi:10.1037/a0023242. PMID 21534697.

- Hayes, Steven C.; Strosahl, Kirk D.; Wilson, Kelly G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-57230-481-9.

- Hayes, Steven C.; Wilson, Kelly G.; Gifford, Elizabeth V.; Follette, Victoria M.; Strosahl, K. (1996). "Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment" (PDF). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 64 (6): 1152–68. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.597.5521 . doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1152. PMID 8991302.