Related Research Articles

Rudolf Karl Augstein was a German journalist, editor, publicist, and politician. He was one of the most influential German journalists, founder and part-owner of Der Spiegel magazine. As a politician, he was a member of the Bundestag for the Free Democratic Party of Germany (FDP) between November 1972 and January 1973.

Joachim Clemens Fest was a German historian, journalist, critic and editor who was best known for his writings and public commentary on Nazi Germany, including a biography of Adolf Hitler and books about Albert Speer and German resistance to Nazism. He was a leading figure in the debate among German historians about the Nazi era. In recent years his writings have earned both praise and strong criticism.

The Frankfurter Zeitung was a German-language newspaper that appeared from 1856 to 1943. It emerged from a market letter that was published in Frankfurt. In Nazi Germany, it was considered the only mass publication not completely controlled by the Propagandaministerium under Joseph Goebbels.

The Historikerstreit was a dispute in the late 1980s in West Germany between conservative and left-of-center academics and other intellectuals about how to incorporate Nazi Germany and the Holocaust into German historiography, and more generally into the German people's view of themselves. The dispute was initiated with the Bitburg controversy, which related to a commemorative service at a German military cemetery where members of the Waffen-SS were buried. The service was attended by President of the United States Ronald Reagan, who had been invited by the West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. The Bitburg ceremony was widely interpreted in Germany as the beginning of the "normalization" of the nation's Nazi past, and inspired a slew of criticisms and defenses that made up the initiating arguments of the Historikerstreit. The dispute quickly outgrew the initial context of the Bitburg controversy, however, and became a series of broader historiographic, political, and critical debates about how the episode of the Holocaust should be understood in Germany's history and identity.

Stéphane Courtois is a French historian and university professor, a director of research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), professor at the Catholic Institute of Higher Studies (ICES) in La Roche-sur-Yon, and director of a collection specialized in the history of communist movements and communist states.

Hans Mommsen was a German historian, known for his studies in German social history, for his functionalist interpretation of the Third Reich, and especially for arguing that Adolf Hitler was a weak dictator. Descended from Nobel Prize-winning historian Theodor Mommsen, he was a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

Andreas Fritz Hillgruber was a conservative German historian who was influential as a military and diplomatic historian who played a leading role in the Historikerstreit of the 1980s. In his controversial book Zweierlei Untergang, he wrote that historians should "identify" with the Wehrmacht fighting on the Eastern Front and asserted that there was no moral difference between Allied policies towards Germany in 1944 and 1945 and the genocide waged against the Jews. The British historian Richard J. Evans wrote that Hillgruber was a great historian whose once-sterling reputation was in ruins as a result of the Historikerstreit.

Klaus Hildebrand is a German liberal-conservative historian whose area of expertise is 19th–20th-century German political and military history.

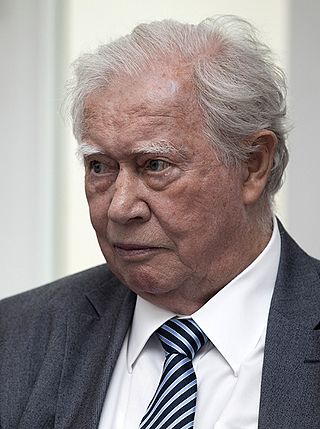

Karl Dietrich Bracher was a German political scientist and historian of the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany. Born in Stuttgart, Bracher was awarded a Ph.D. in the classics by the University of Tübingen in 1948 and subsequently studied at Harvard University from 1949 to 1950. During World War II, he served in the Wehrmacht and was captured by the Americans while serving in Tunisia in 1943. Bracher taught at the Free University of Berlin from 1950 to 1958 and at the University of Bonn since 1959. In 1951, Bracher married Dorothee Schleicher, the niece of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. They had two children.

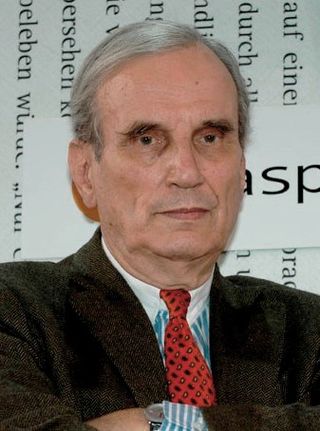

Ernst Nolte was a German historian and philosopher. Nolte's major interest was the comparative studies of fascism and communism. Originally trained in philosophy, he was professor emeritus of modern history at the Free University of Berlin, where he taught from 1973 until his 1991 retirement. He was previously a professor at the University of Marburg from 1965 to 1973. He was best known for his seminal work Fascism in Its Epoch, which received widespread acclaim when it was published in 1963. Nolte was a prominent conservative academic from the early 1960s and was involved in many controversies related to the interpretation of the history of fascism and communism, including the Historikerstreit in the late 1980s. In later years, Nolte focused on Islamism and "Islamic fascism".

Eberhard Jäckel was a German historian. In the 1980s, he was a principal protagonist in the Historians' Dispute (Historikerstreit) over how to incorporate Nazi Germany and the Holocaust into German historiography and over Hitler's intentions.

Sonderweg refers to the theory in German historiography that considers the German-speaking lands or the country of Germany itself to have followed a course from aristocracy to democracy unlike any other in Europe.

Rainer Zitelmann is a German historian, sociologist, author, management consultant and real estate expert.

Franz Borkenau was an Austrian writer. Borkenau was born in Vienna, Austria, the son of a civil servant. As a university student in Leipzig, his main interests were Marxism and psychoanalysis. Borkenau is known as one of the pioneers of the totalitarianism theory.

Michael Stürmer is a conservative German historian best known for his role in the Historikerstreit of the 1980s, for his geographical interpretation of German history and for an admiring 2008 biography of the Russian politician Vladimir Putin.

Jürgen Kocka is a German historian.

Various historians and other authors have carried out a comparison of Nazism and Stalinism, with particular consideration to the similarities and differences between the two ideologies and political systems, the relationship between the two regimes, and why both came to prominence simultaneously. During the 20th century, comparisons of Nazism and Stalinism were made on totalitarianism, ideology, and personality cult. Both regimes were seen in contrast to the liberal democratic Western world, emphasising the similarities between the two.

Hotel Lux (Люксъ) was a hotel in Moscow during the Soviet Union, housing many leading exiled and visiting Communists. During the Nazi era, exiles from all over Europe went there, particularly from Germany. A number of them became leading figures in German politics in the postwar era. Initial reports of the hotel were good, although its problem with rats was mentioned as early as 1921. Communists from more than 50 countries came for congresses, for training or to work. By the 1930s, Joseph Stalin had come to regard the international character of the hotel with suspicion and its occupants as potential spies. His purges created an atmosphere of fear among the occupants, who were faced with mistrust, denunciations, and nightly arrests. The purges at the hotel peaked between 1936 and 1938. Germans who had fled Nazi Germany, seeking safety in the Soviet Union, were interrogated, arrested, tortured, and sent to forced labour camps. Most of the 178 leading German communists who were killed in Stalin's purges were residents of Hotel Lux.

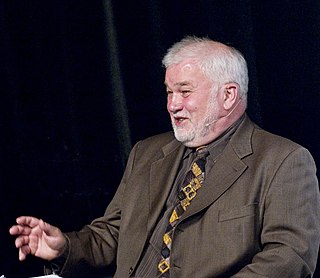

Jörg Baberowski is a German historian and Professor of Eastern European History at the Humboldt University of Berlin. He studies the history of the Soviet Union and Stalinist violence. Baberowski earlier served as Director of the Historical Institute and Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy I at the Humboldt University in Berlin.

Horst Boog was a German historian who specialised in the history of Nazi Germany and World War II. He was the research director at the Military History Research Office (MGFA). Boog was a contributor to several volumes of the seminal work Germany and the Second World War from the MGFA. He was an expert on the Luftwaffe and the German side of the aerial war in Europe during World War II.

References

- Fitzsimons, M.A. “Apology to Richard Löwenthal” page 285 from The Review of Politics, Volume 25, Issue # 2 April 1963.

- (Editors) Hannelore Horn, Alexander Schwan & Thomas Weingartner Sozialismus in Theorie und Praxis: Festschrift für Richard Löwenthal zum 70. Geburtstag am 15. April 1978, Berlin; New York: de Gruyter, 1978 ISBN 3-11-007221-1.

- Second Chance: Two Centuries of German-Speaking Jews in the United Kingdom, edited by Werner E. Mosse, Julius Carlebach, Gerhard Hirschfeld, Aubrey Newman, Arnold Paucker, Peter Pulzer, J.C.B. Mohr, London, 1991, ISBN 978-3-16-145741-8.

- Laqueur, Walter The Fate of the Revolution: Interpretations of Soviet history from 1917 to the Present, New York: Scribner's, 1987 ISBN 0-684-18903-8.

- Bavaj, Riccardo Western Civilization and the Acceleration of Time. Richard Löwenthal’s Reflections on a Crisis of the West in the Aftermath of the Student Revolt of 1968, in: Themenportal Europaeische Geschichte (2010), URL: http://www.europa.clio-online.de/2010/Article=434.