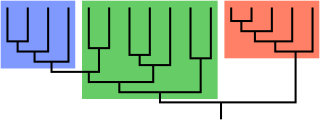

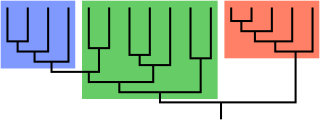

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic with respect to the excluded subgroups. In contrast, a monophyletic grouping includes a common ancestor and all of its descendants.

A cladogram is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to descendants, nor does it show how much they have changed, so many differing evolutionary trees can be consistent with the same cladogram. A cladogram uses lines that branch off in different directions ending at a clade, a group of organisms with a last common ancestor. There are many shapes of cladograms but they all have lines that branch off from other lines. The lines can be traced back to where they branch off. These branching off points represent a hypothetical ancestor which can be inferred to exhibit the traits shared among the terminal taxa above it. This hypothetical ancestor might then provide clues about the order of evolution of various features, adaptation, and other evolutionary narratives about ancestors. Although traditionally such cladograms were generated largely on the basis of morphological characters, DNA and RNA sequencing data and computational phylogenetics are now very commonly used in the generation of cladograms, either on their own or in combination with morphology.

In cladistics or phylogenetics, an outgroup is a more distantly related group of organisms that serves as a reference group when determining the evolutionary relationships of the ingroup, the set of organisms under study, and is distinct from sociological outgroups. The outgroup is used as a point of comparison for the ingroup and specifically allows for the phylogeny to be rooted. Because the polarity (direction) of character change can be determined only on a rooted phylogeny, the choice of outgroup is essential for understanding the evolution of traits along a phylogeny.

In phylogenetics, long branch attraction (LBA) is a form of systematic error whereby distantly related lineages are incorrectly inferred to be closely related. LBA arises when the amount of molecular or morphological change accumulated within a lineage is sufficient to cause that lineage to appear similar to another long-branched lineage, solely because they have both undergone a large amount of change, rather than because they are related by descent. Such bias is more common when the overall divergence of some taxa results in long branches within a phylogeny. Long branches are often attracted to the base of a phylogenetic tree, because the lineage included to represent an outgroup is often also long-branched. The frequency of true LBA is unclear and often debated, and some authors view it as untestable and therefore irrelevant to empirical phylogenetic inference. Although often viewed as a failing of parsimony-based methodology, LBA could in principle result from a variety of scenarios and be inferred under multiple analytical paradigms.

Hystricomorpha is a term referring to families and orders of rodents which has had many definitions throughout its history. In the broadest sense, it refers to any rodent with a hystricomorphous zygomasseteric system. This includes the Hystricognathi, Ctenodactylidae, Anomaluridae, and Pedetidae. Molecular and morphological results suggest the inclusion of the Anomaluridae and Pedetidae in Hystricomorpha may be suspect. Based on Carleton & Musser 2005, these two families are discussed here as representing a distinct suborder Anomaluromorpha.

Phyllodocida is an order of polychaete worms in the subclass Aciculata. These worms are mostly marine, though some are found in brackish water. Most are active benthic creatures, moving over the surface or burrowing in sediments, or living in cracks and crevices in bedrock. A few construct tubes in which they live and some are pelagic, swimming through the water column. There are estimated to be more than 4,600 accepted species in the order.

Errantia is a diverse group of marine polychaete worms in the phylum Annelida. Traditionally a subclass of the paraphyletic class Polychaeta, it is currently regarded as a monophyletic group within the larger Pleistoannelida, composed of Errantia and Sedentaria. These worms are found worldwide in marine environments and brackish water.

Kirk J. Fitzhugh is the curator at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, a position he has held since 1990. His research focuses on the systematics of polychaetes and on the philosophical foundations of evolutionary theory. Fitzhugh is a critic of DNA barcoding methods as a technical substitute for systematics. He attends Willi Hennig Society meetings where he has argued that "synapomorphy as evidence does not meet the scientific standard of independence...a particularly serious challenge to phylogenetic systematics, because it denies that the most severely tested and least disconfirmed cladogram can also maximize explanatory power." His graduate supervisor was V. A. Funk, from the U.S. National Herbarium, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution MRC. He completed his doctoral thesis on Systematics and phylogeny of Sabellid polychaetes in 1988 while he was a research scientist at the LA County museum He married a lawyer named Nancy E. Gold in 1989.

Panorpida or Mecopterida is a proposed superorder of Holometabola. The conjectured monophyly of the Panorpida is historically based on morphological evidence, namely the reduction or loss of the ovipositor and several internal characteristics, including a muscle connecting a pleuron and the first axillary sclerite at the base of the wing, various features of the larval maxilla and labium, and basal fusion of CuP and A1 veins in the hind wings. The monophyly of the Panorpida is supported by recent molecular data.

Prosphaerosyllis battiri is a species belonging to the phylum Annelida, a group known as the segmented worms. The species name comes from an Aboriginal word, battiri, meaning 'rough'. Prosphaerosyllis battiri is a species characterized by having only partially fused palps, an unretracted prostomium on its peristomium or showing only slight retraction, the shape of its dorsal cirri and its arrangement of papillae, being numerous anteriorly while less numerous posteriorly. It resembles Prosphaerosyllis semiverrucosa, but its arrangement of dorsal papillae is reversed.

Salvatoria koorineclavata is a species belonging to the phylum Annelida, a group known as the segmented worms. A related species in Australia has been described as Brania clavata and subsequently as Salvatoria clavata. While similar, the Australian species has a longer pharynx and proventricle; at the same time, blades of chaetae are present in the Australian species, with longer and upwards curved spines, which are straight in S. clavata; its pharyngeal tooth is located more anteriorly than in S. clavata. Other global species, like those in the genus Brania, are also similar to S. koorineclavata. Salvatoria californiensis has similar chaetae, with shorter spines and less developed teeth. Its acicula lacks a defined acute tip, and the proventricle is quite shorter, running through 5 segments in S. koorineclavata, with fewer rows of muscle cells. The species name comes from an Aboriginal word, Koorine, meaning "daughter", due to the similarity of the Australian species to the European species of S. clavata.

Erinaceusyllis is a genus belonging to the phylum Annelida, a group known as the segmented worms. Erinaceusyllis is a marine genus, while some of its species are possibly cosmopolitan. Its type species is Erinaceusyllis erinaceus, formerly Sphaerosyllis erinaceus. As of 2015, at least 12 species have been described, namely E. belizensis, E. bidentata, E centroamericana, E. cirripapillata, E. cryptica, E. erinaceus, E ettiennei, E. hartmannschroederae, E horrocksensis, E. kathrynae, E. opisthodentata, E. serratosetosa. The family contains two other genera, Sphaerosyllis and Prosphaerosyllis.

Erinaceusyllis ettiennei is a species belonging to the phylum Annelida. It was first found in mud at a depth of 5 metres (16 ft) in Halifax Bay, north of Townsville, Queensland.

Erinaceusyllis cirripapillata is a species belonging to the phylum Annelida. It was first found in the mud at a depth of 3 m (9.8 ft) New South Wales' Richmond River.

Erinaceusyllis hartmannschroederae is a species belonging to the phylum Annelida. It is found in the intertidal zone to depths of 15 metres (49 ft). The species is named in honour of Gesa Hartmann-Schröder, an expert on syllid species.

Erinaceusyllis kathrynae is a species belonging to the phylum Annelida. It has been found at depths of 3–18 m (9.8–59 ft) in coral rubble, sponges, and coralline algae on both the west and east coasts of Australia. It is named for Kathryn Attwood of the Australian Museum.

Sphaerosyllis bardukaciculata is a species belonging to the phylum Annelida, a group known as the segmented worms. Sphaerosyllis bardukaciculatan is similar to Sphaerosyllis aciculata from Florida; its chaetae are almost identical; the former, however, differs by having longer antennae and anal cirri, as well as parapodial glands with granular material. The animal's name is derived from the Aboriginal word barduk, meaning "near", alluding to the aforementioned likeness with S. aciculata.

Sphaerosyllis georgeharrisoni is a species belonging to the phylum Annelida, a group known as the segmented worms. Sphaerosyllis georgeharrisoni is distinct by its large parapodial glands with hyaline material; by its small size; short proventricle; a median antenna that is inserted posteriorly to the lateral antennae; as well as long pygidial papillae. Juveniles of S. hirsuta are very similar to this species. Sphaerosyllis pygipapillata has all of its antennae aligned, a smooth dorsum, while its pygidial papillae are longer and slender. The species' name honours George Harrison, musician who died prior to the species' describing article's publication.

Syllidae, commonly known as the necklace worms, is a family of small to medium-sized polychaete worms. Syllids are distinguished from other polychaetes by the presence of a muscular region of the anterior digestive tract known as the proventricle.

The Colubroides are a clade in the suborder Serpentes (snakes). It contains over 85% of all the extant species of snakes. The largest family is Colubridae, but it also includes at least six other families, at least four of which were once classified as "Colubridae" before molecular phylogenetics helped in understanding their relationships. It has been found to be monophyletic.