The Treaty of Cahuenga, also called the Capitulation of Cahuenga, was an 1847 agreement that ended the Conquest of California, resulting in a ceasefire between Californios and Americans. The treaty was signed at the Campo de Cahuenga on 13 January 1847, ending the fighting of the Mexican–American War within Alta California. The treaty was drafted in both English and Spanish by José Antonio Carrillo and signed by John C. Frémont, representing the American forces, and Andrés Pico, representing the Mexican forces.

Alta California, also known as Nueva California among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of Las Californias, but was made a separate province in 1804. Following the Mexican War of Independence, it became a territory of Mexico in April 1822 and was renamed Alta California in 1824.

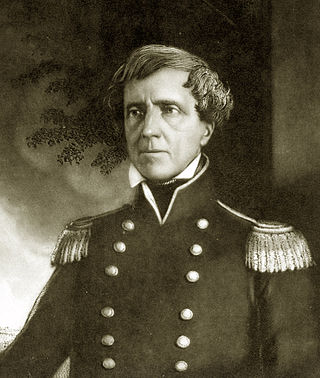

Stephen Watts Kearny was one of the foremost antebellum frontier officers of the United States Army. He is remembered for his significant contributions in the Mexican–American War, especially the conquest of California. The Kearny code, proclaimed on September 22, 1846, in Santa Fe, established the law and government of the newly acquired territory of New Mexico and was named after him. His nephew was Major General Philip Kearny of American Civil War fame.

Californios are Hispanic Californians, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there since 1683 and is made up of varying Spanish and Mexican origins, including criollos, Mestizos, Indigenous Californian peoples, and small numbers of Mulatos. Alongside the Tejanos of Texas and Neomexicanos of New Mexico and Colorado, Californios are part of the larger Spanish-American/Mexican-American/Hispano community of the United States, which has inhabited the American Southwest and the West Coast since the 16th century. Some may also identify as Chicanos, a term that came about in the 1960s.

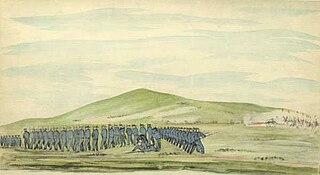

The Battle of San Pasqual, also spelled San Pascual, was a military encounter that occurred during the Mexican–American War in what is now the San Pasqual Valley community of the city of San Diego, California. The series of military skirmishes ended with both sides claiming victory, and the victor of the battle is still debated. On December 6 and December 7, 1846, General Stephen W. Kearny's US Army of the West, along with a small detachment of the California Battalion led by a Marine Lieutenant, engaged a small contingent of Californios and their Presidial Lancers Los Galgos, led by Major Andrés Pico. After U.S. reinforcements arrived, Kearny's troops were able to reach San Diego.

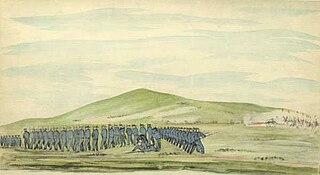

The Battle of Río San Gabriel, fought on 8 January 1847, was a decisive action of the California campaign of the Mexican–American War and occurred at a ford of the San Gabriel River, at what are today parts of the cities of Whittier, Pico Rivera and Montebello, about ten miles south-east of downtown Los Angeles.

The Pacific Squadron was part of the United States Navy squadron stationed in the Pacific Ocean in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Initially with no United States ports in the Pacific, they operated out of storeships which provided naval supplies and purchased food and obtained water from local ports of call in the Hawaiian Islands and towns on the Pacific Coast. Throughout the history of the Pacific Squadron, American ships fought against several enemies. Over one-half of the United States Navy would be sent to join the Pacific Squadron during the Mexican–American War. During the American Civil War, the squadron was reduced in size when its vessels were reassigned to Atlantic duty. When the Civil War was over, the squadron was reinforced again until being disbanded just after the turn of the 20th century.

The Battle of La Mesa was the final battle of the California Campaign during the Mexican–American War, occurring on January 9, 1847, in present-day Vernon, California, the day after the Battle of Rio San Gabriel. The battle was a victory for the United States Army under Commodore Robert F. Stockton and General Stephen Watts Kearny.

Andrés Pico was a Californio who became a successful rancher, fought in the contested Battle of San Pascual during the Mexican–American War, and negotiated promises of post-war protections for Californios in the 1847 Treaty of Cahuenga. After California became one of the United States, Pico was elected to the state Assembly and Senate. He was appointed as the commanding brigadier general of the state militia during the U.S. Civil War.

The Battle of Dominguez Rancho or The Battle of the Old Woman's Gun or The Battle of Dominguez Hills took place on October 8 and October 9, 1846, was a military engagement of the Mexican–American War that took place within Manuel Dominguez's 75,000 acre Rancho San Pedro. Captain José Antonio Carrillo, leading fifty California troops, successfully held off an invasion of Pueblo de Los Angeles by some 300 United States Marines, capturing for the first time in the few instances of U.S. history the U.S. Colors upon the battlefield, while under the command of US Navy Captain William Mervine, who was attempting to recapture the town after the Siege of Los Angeles. By strategically running horses across the dusty Dominguez Hills, while transporting their single small cannon to various sites, Carrillo and his troops convinced the Americans they had encountered a large enemy force. Faced with heavy casualties and the superior fighting skills displayed by the Californios, the remaining Marines were forced to retreat to their ships docked in San Pedro Bay.

The Battle of the Natividad took place on November 16, 1846, in the Salinas Valley, in present-day Monterey County, California, United States, during the California Campaign of the Mexican–American War, between United States organized California militia and loyalist Mexican militia.

Major Archibald H. Gillespie was an officer in the United States Marine Corps during the Mexican–American War.

General José María Flores was a Captain in the Mexican Army and was a member of la otra banda. He was appointed Governor and Comandante Generalpro tem of Alta California from November 1846 to January 1847, and defended California against the Americans during the Mexican–American War.

The history of California can be divided into the Native American period, the European exploration period (1542–1769), the Spanish colonial period (1769–1821), the Mexican period (1821–1848), and United States statehood. California was one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse areas in pre-Columbian North America. After contact with Spanish explorers, many of the Native Americans died from foreign diseases. Finally, in the 19th century there was a genocide by United States government and private citizens, which is known as the California genocide.

The Siege of Los Angeles, sometimes known as the Battle of Los Angeles, was a military response by armed Mexican civilians to the August 1846 occupation of the Pueblo de Los Ángeles by the United States Marines during the Mexican–American War.

Captain José Antonio Ezequiel Carrillo (1796–1862) was a Californio politician, ranchero, and signer of the Californian Constitution in 1849. He served three terms as Alcalde of Los Angeles (mayor).

The California Battalion was formed during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) in present-day California, United States. It was led by U.S. Army Brevet Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont and composed of his cartographers, scouts and hunters and the California Volunteer Militia formed after the Bear Flag Revolt. The battalion's formation was officially authorized by Commodore Robert F. Stockton, commanding officer of the U.S. Navy Pacific Squadron.

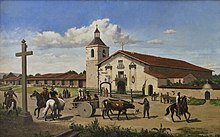

The Battle of Santa Clara, nicknamed the "Battle of the Mustard Stalks", was a skirmish during the Mexican–American War, fought on January 2, 1847, 2+1⁄2 miles west of Mission Santa Clara de Asís in California. It was the only engagement of its type in Northern California during the war.

The Conquest of California, also known as the Conquest of Alta California or the California Campaign, was an important military campaign of the Mexican–American War carried out by the United States in Alta California, then a part of Mexico. The conquest lasted from 1846 into 1847, until military leaders from both the Californios and Americans signed the Treaty of Cahuenga, which ended the conflict in California.