Anubis, also known as Inpu, Inpw, Jnpw, or Anpu in Ancient Egyptian, is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Osiris is the god of fertility, agriculture, the afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation in ancient Egyptian religion. He was classically depicted as a green-skinned deity with a pharaoh's beard, partially mummy-wrapped at the legs, wearing a distinctive atef crown, and holding a symbolic crook and flail. He was one of the first to be associated with the mummy wrap. When his brother Set cut him up into pieces after killing him, Osiris' wife Isis found all the pieces and wrapped his body up, enabling him to return to life. Osiris was widely worshipped until the decline of ancient Egyptian religion during the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire.

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her slain brother and husband, the divine king Osiris, and produces and protects his heir, Horus. She was believed to help the dead enter the afterlife as she had helped Osiris, and she was considered the divine mother of the pharaoh, who was likened to Horus. Her maternal aid was invoked in healing spells to benefit ordinary people. Originally, she played a limited role in royal rituals and temple rites, although she was more prominent in funerary practices and magical texts. She was usually portrayed in art as a human woman wearing a throne-like hieroglyph on her head. During the New Kingdom, as she took on traits that originally belonged to Hathor, the preeminent goddess of earlier times, Isis was portrayed wearing Hathor's headdress: a sun disk between the horns of a cow.

The Ides of March is the day on the Roman calendar marked as the Idus, roughly the midpoint of a month, of Martius, corresponding to 15 March on the Gregorian calendar. It was marked by several major religious observances. In 44 BC, it became notorious as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar, which made the Ides of March a turning point in Roman history.

Roman Egypt was an imperial province of the Roman Empire from 30 BC to AD 641. The province encompassed most of modern-day Egypt except for the Sinai. It was bordered by the provinces of Crete and Cyrenaica to the west and Judaea, later Arabia Petraea, to the East.

A serapeum is a temple or other religious institution dedicated to the syncretic Greco-Egyptian deity Serapis, who combined aspects of Osiris and Apis in a humanized form that was accepted by the Ptolemaic Greeks of Alexandria. There were several such religious centers, each of which was called a serapeion/serapeum or poserapi, coming from an Egyptian name for the temple of Osiris-Apis.

Agathos Daimon originally was a lesser deity (daemon) of classical ancient Greek religion and Graeco-Egyptian religion. In his original Greek form, he served as a household god, to whom, along with Zeus Soter, libations were made after a meal. In later (post-)Ptolemaic antiquity he took on two partially distinct roles; one as the Agathos Daimon a prominent serpentine civic god, who served as the special protector of Alexandria. The other as a genus of serpentine household gods, the Agathoi Daimones, individual protectors of the homes in which they were worshipped.

Interpretatio graeca, or "interpretation by means of Greek [models]", refers to the tendency of the ancient Greeks to identify foreign deities with their own gods. It is a discourse used to interpret or attempt to understand the mythology and religion of other cultures; a comparative methodology using ancient Greek religious concepts and practices, deities, and myths, equivalencies, and shared characteristics.

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian god. A syncretic deity derived from the worship of the Egyptian Osiris and Apis, Serapis was extensively popularized in the third century BC on the orders of Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter, as a means to unify the Greek and Egyptian subjects of the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

The concept of Hellenistic religion as the late form of Ancient Greek religion covers any of the various systems of beliefs and practices of the people who lived under the influence of ancient Greek culture during the Hellenistic period and the Roman Empire. There was much continuity in Hellenistic religion: people continued to worship the Greek gods and to practice the same rites as in Classical Greece.

Menouthis was a sacred city in ancient Egypt, devoted to the Egyptian goddess Isis and god Serapis. The city was probably submerged under the sea as a result of catastrophic natural causes: earthquakes or Nile flood. Land in the bay area was subject to rising sea levels, earthquakes, and tsunamis, parts of it apparently becoming submerged after a process of soil liquefaction sometime at the end of the 2nd century BC.

The Navigium Isidis or Isidis Navigium was an annual ancient Roman religious festival in honor of the goddess Isis, held on March 5. The festival outlived Christian persecution by Theodosius (391) and Arcadius' persecution against the Roman religion (395).

In the Roman Empire, the Pelusia was a religious festival held March 20 in honor of Isis and her child Harpocrates. It would have coincided with the second day of the Quinquatria, a five-day festival to Minerva. The holiday was not a part of the Roman calendar before the mid-1st century AD, but had been added by the time of Marcus Aurelius (161–180). It is preserved in the Calendar of Filocalus as an official holiday.

Martius or mensis Martius ("March") was the first month of the ancient Roman year until possibly as late as 153 BC. After that time, it was the third month, following Februarius (February) and preceding Aprilis (April). Martius was one of the few Roman months named for a deity, Mars, who was regarded as an ancestor of the Roman people through his sons Romulus and Remus.

The mysteries of Isis were religious initiation rites performed in the cult of the Egyptian goddess Isis in the Greco-Roman world. They were modeled on other mystery rites, particularly the Eleusinian mysteries in honor of the Greek goddesses Demeter and Persephone, and originated sometime between the third century BCE and the second century CE. Despite their mainly Hellenistic origins, the mysteries alluded to beliefs from ancient Egyptian religion, in which the worship of Isis arose, and may have incorporated aspects of Egyptian ritual. Although Isis was worshipped across the Greco-Roman world, the mystery rites are only known to have been practiced in a few regions. In areas where they were practiced, they served to strengthen devotees' commitment to the Isis cult, although they were not required to worship her exclusively, and devotees may have risen in the cult's hierarchy by undergoing initiation. The rites may also have been thought to guarantee that the initiate's soul, with the goddess's help, would continue after death into a blissful afterlife.

In the Roman Empire, the Lychnapsia was a festival of lamps on August 12, widely regarded by scholars as having been held in honor of Isis. It was thus one of several official Roman holidays and observances that publicly linked the cult of Isis with Imperial cult. It is thought to be a Roman adaptation of Egyptian religious ceremonies celebrating the birthday of Isis. By the 4th century, Isiac cult was thoroughly integrated into traditional Roman religious practice, but evidence that Isis was honored by the Lychnapsia is indirect, and lychnapsia is a general word in Greek for festive lamp-lighting. In the 5th century, lychnapsia could be synonymous with lychnikon as a Christian liturgical office.

November or mensis November was originally the ninth of ten months on the Roman calendar, following October and preceding December. It had 29 days. In the reform that resulted in a 12-month year, November became the eleventh month, but retained its name, as did the other months from September through December. A day was added to November during the Julian calendar reform in the mid-40s BC.

The Temple of Isis and Serapis was a double temple in Rome dedicated to the Egyptian deities Isis and Serapis on the Campus Martius, directly to the east of the Saepta Julia. The temple to Isis, the Iseum Campense, stood across a plaza from the Serapeum dedicated to Serapis. The remains of the Temple of Serapis now lie under the church of Santo Stefano del Cacco, and the Temple of Isis lay north of it, just east of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. Both temples were made up of a combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic architectural styles. Much of the artwork decorating the temples used motifs evoking Egypt, and they contained several genuinely Egyptian objects, such as couples of obelisks in red or pink granite from Syene.

The decline of ancient Egyptian religion is largely attributed to the spread of Christianity in Egypt. Its strict monotheistic nature did not allow the syncretism seen between ancient Egyptian religion and other polytheistic religions, such as that of the Romans. Although religious practices within Egypt stayed relatively constant despite contact with the greater Mediterranean world, such as with the Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans, Christianity directly competed with the native religion. Even before the Edict of Milan in AD 313, which legalised Christianity in the Roman Empire, Egypt became an early centre of Christianity, especially in Alexandria where numerous influential Christian writers of antiquity such as Origen and Clement of Alexandria lived much of their lives, and native Egyptian religion may have put up little resistance to the permeation of Christianity into the province.

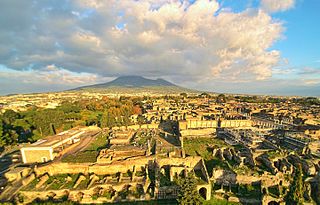

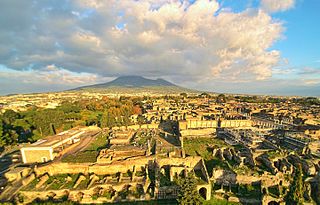

Several non-native societies had an influence on Ancient Pompeian culture. Historians’ interpretation of artefacts, preserved by the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79, identify that such foreign influences came largely from Greek and Hellenistic cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean, including Egypt. Greek influences were transmitted to Pompeii via the Greek colonies in Magna Graecia, which were formed in the 8th century BC. Hellenistic influences originated from Roman commerce, and later conquest of Egypt from the 2nd century BC.