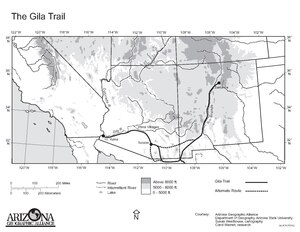

The Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail is a 1,210-mile (1,950 km) trail extending from Nogales on the U.S.-Mexico border in Arizona, through the California desert and coastal areas in Southern California and the Central Coast region to San Francisco. The trail commemorates the 1775–1776 land route that Spanish commander Juan Bautista de Anza took from the Sonora y Sinaloa Province of New Spain in Colonial Mexico through to Las Californias Province. The goal of the trip was to establish a mission and presidio on the San Francisco Bay. The trail was an attempt to ease the course of Spanish colonization of California by establishing a major land route north for many to follow. It was used for about five years before being closed by the Quechan (Yuma) Indians in 1781 and kept closed for the next 40 years. It is a National Historic Trail administered by the National Park Service and was also designated a National Millennium Trail.

Apache Pass, also known by its earlier Spanish name Puerto del Dado, is a historic mountain pass in the U.S. state of Arizona between the Dos Cabezas Mountains and Chiricahua Mountains at an elevation of 5,110 feet (1,560 m). It is approximately 20 miles (32 km) east-southeast of Willcox, Arizona, in Cochise County.

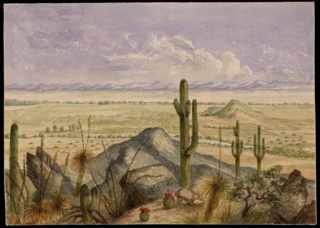

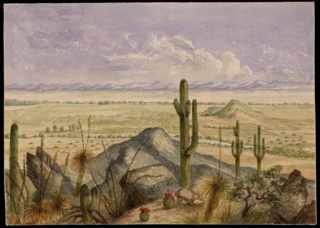

El Camino del Diablo, also known as El Camino del Muerto, Sonora Trail, Sonoyta-Yuma Trail, Yuma-Caborca Trail, and Old Yuma Trail, is a historic 250-mile (400 km) road that passes through some of the most remote and inhospitable terrain of the Sonoran Desert in Pima County and Yuma County, Arizona. The name refers to the harsh, unforgiving conditions on the trail.

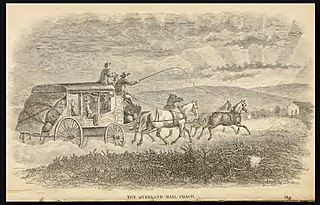

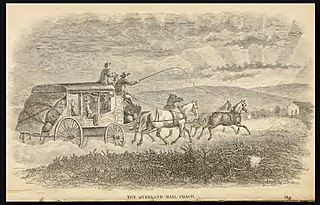

In the history of the American frontier, pioneers built overland trails throughout the 19th century, especially between 1829 and 1870, as an alternative to sea and railroad transport. These immigrants began to settle much of North America west of the Great Plains as part of the mass overland migrations of the mid-19th century. Settlers emigrating from the eastern United States did so with various motives, among them religious persecution and economic incentives, to move from their homes to destinations further west via routes such as the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails. After the end of the Mexican–American War in 1849, vast new American conquests again encouraged mass immigration. Legislation like the Donation Land Claim Act and significant events like the California Gold Rush further encouraged settlers to travel overland to the west.

The Butterfield Overland Mail in California was created by the United States Congress on March 3, 1857, and operated until June 30, 1861. Subsequently, other stage lines operated along the Butterfield Overland Mail in route in Alta California until the Southern Pacific Railroad arrived in Yuma, Arizona in 1877.

Alamo Mucho Station, the misspelled name of Alamo Mocho Station was one of the original Butterfield Overland Mail stations located south of the Mexican border, in Baja California. Its location is 0.5 miles south-southeast of the Mexicali International Airport Terminal building.

The San Antonio–San Diego Mail Line, also known as the Jackass Mail, was the earliest overland stagecoach and mail operation from the Eastern United States to California in operation between 1857 and 1861. It was created, organized and financed by James E. Birch the head of the California Stage Company. Birch was awarded the first contract for overland service on the "Southern Route", designated Route 8076. This contract required a semi-monthly service in four-horse coaches, scheduled to leave San Antonio and San Diego on the ninth and the 24th of each month, with 30 days allowed for each trip.

The Butterfield Overland Mail was a transport and mail delivery system that employed stagecoaches that travelled on a specific route between St. Louis, Missouri and San Francisco, California and which passed through the New Mexico Territory. It was created by the United States Congress on March 3, 1857, and operated until March 30, 1861. The route that was operated extended from where the ferry across the Colorado River to Fort Yuma Station, California was located, through New Mexico Territory via, Tucson to the Rio Grande and Mesilla, New Mexico then south to Franklin, Texas, midpoint on the route. The New Mexico Territory mail route was divided into two divisions each under a superintendent. Tucson was the headquarters of the 3rd Division of the Butterfield Overland Mail Company. Franklin Station in the town of Franklin,, was the headquarters of the 4th Division.

The Butterfield Overland Mail route in Baja California was created as a result of an act by the United States Congress on March 3, 1857, and operated until June 30, 1861 as part of the Second Division of the route. Subsequently other stage lines operated along the route until the Southern Pacific Railroad arrived in Yuma, Arizona.

Vallecito, in San Diego County, California, is an oasis of cienegas and salt grass along Vallecito Creek and a former Kumeyaay settlement on the edge of the Colorado Desert in the Vallecito Valley. Its Spanish name is translated as "little valley". Vallecito was located at the apex of the gap in the Carrizo Badlands created by Carrizo Creek and its wash in its lower reach, to which Vallecito Creek is a tributary. The springs of Vallecito, like many in the vicinity, are a product of the faults that run along the base of the Peninsular Ranges to the west.

Pima Villages, sometimes mistakenly called the Pimos Villages in the 19th century, were the Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Pee-Posh (Maricopa) villages in what is now the Gila River Indian Community in Pinal County, Arizona. First, recorded by Spanish explorers in the late 17th century as living on the south side of the Gila River, they were included in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, then in Provincias of Sonora, Ostimuri y Sinaloa or New Navarre to 1823. Then from 1824 to 1830, they were part of the Estado de Occidente of Mexico and from September 1830 they were part of the state of Sonora. These were the Pima villages encountered by American fur trappers, traders, soldiers and travelers along the middle Gila River from 1830s into the later 19th century. The Mexican Cession following the Mexican American War left them part of Mexico. The 1853 Gadsden Purchase made their lands part of the United States, Territory of New Mexico. During the American Civil War, they became part of the Territory of Arizona.

San Simon River is an ephemeral river, or stream running through the San Simon Valley in Graham and Cochise County, Arizona and Hidalgo County, New Mexico. Its mouth is at its confluence with the Gila River at Safford in Graham County. Its source is located at 31°51′21″N109°01′27″W.

Nugents Pass or Nugent's Pass is a gap at an elevation of 4,593 feet (1,400 m) in Cochise County, Arizona. The pass was named for John Nugent, who provided notes of his journey with a party of Forty-Niners across what became the Tucson Cutoff to Lt. John G. Parke, on expedition to identify a feasible railroad route from the Pima Villages to the Rio Grande.

Stein's Pass, is a gap or mountain pass through the Peloncillo Mountains of Hidalgo County, New Mexico. The pass was named after United States Army Major Enoch Steen, who camped nearby in 1856, as he explored the recently acquired Gadsden Purchase. The pass is in the form of a canyon cut through the mountains through which Steins Creek flows to the west just west of the apex of the pass to the canyon mouth at 32°13′19″N109°01′48″W.

Cienega of San Simon, was a cienega, an area of springs 13 miles up the San Simon River from San Simon Station, in Cochise County, Arizona.

The Tucson Cutoff was a significant change in the route of the Southern Emigrant Trail. It became generally known after a party of Forty-Niners led by Colonel John Coffee Hays followed a route suggested to him by a Mexican Army officer as a shorter route than Cooke's Wagon Road which passed farther south to cross the mountains to the San Pedro River at Guadalupe Pass.

Tres Alamos Wash, an ephemeral stream tributary to the San Pedro River, in Cochise County, Arizona. It runs southwesterly to meet the San Pedro River, across the river from the former settlement of Tres Alamos, Arizona. Tres Alamos Wash passes east and northeastward between the Little Dragoon Mountains and Johnny Lyon Hills to where it arises in a valley east of those heights and west of Allen Flat and the Steele Hills. It has its source at 32°07′45″N110°02′59″W.

Fosters Hole or La Tinaja, was a waterhole on the original route of Cooke's Wagon Road in what is now Sierra County, New Mexico. It is located in narrow crevasse at the foot of a cliff in Jug Canyon that is difficult to spot, except from a few vantage points.

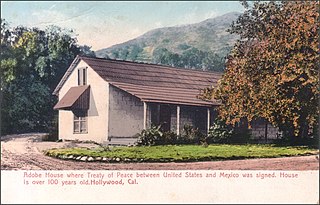

Cooke's Wagon Road or Cooke's Road was the first wagon road between the Rio Grande and the Colorado River to San Diego, through the Mexican provinces of Nuevo México, Chihuahua, Sonora and Alta California, established by Philip St. George Cooke and the Mormon Battalion, from October 19, 1846 to January 29, 1847 during the Mexican–American War. It became the first of the wagon routes between New Mexico and California that with subsequent modifications before and during the California Gold Rush eventually became known as the Southern Trail or Southern Emigrant Trail.

Box Canyon in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park in San Diego County, is a California Historical Landmark No. 472 listed on September 11, 1950. Box Canyon is a desert canyon and mountain pass on the Historic Southern Emigrant Trail. The US troops under General Stephen Watts Kearny and with US scout Kit Carson found Box Canyon and its pass in October 1846. On January 19, 1847, Kearny was the leader of a wagon train with Colonel Philip St. George Cooke and the Mormon Battalion that used Box Canyon to head west. The group used hand tool to widen and clear Box Canyon so the covered wagons could pass. The road through Box Canyon became the first road into Southern Alta California.