Related Research Articles

Nationality is the legal status of belonging to a particular nation, defined as a group of people organized in one country, under one legal jurisdiction, or as a group of people who are united on the basis of culture.

Naturalization is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the United Nations excludes citizenship that is automatically acquired or is acquired by declaration. Naturalization usually involves an application or a motion and approval by legal authorities. The rules of naturalization vary from country to country but typically include a promise to obey and uphold that country's laws and taking and subscribing to an oath of allegiance, and may specify other requirements such as a minimum legal residency and adequate knowledge of the national dominant language or culture. To counter multiple citizenship, some countries require that applicants for naturalization renounce any other citizenship that they currently hold, but whether this renunciation actually causes loss of original citizenship, as seen by the host country and by the original country, will depend on the laws of the countries involved. Arguments for increasing naturalization include reducing backlogs in naturalization applications and reshaping the electorate of the country.

Russians in the Baltic states is a broadly defined subgroup of the Russian diaspora who self-identify as ethnic Russians, or are citizens of Russia, and live in one of the three independent countries — Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — primarily the consequences of the USSR's forced population transfers during occupation. As of 2023, there were approximately 887,000 ethnic Russians in the three countries, having declined from ca 1.7 million in 1989, the year of the last census during the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation of the three Baltic countries.

Nationality law is the law of a sovereign state, and of each of its jurisdictions, that defines the legal manner in which a national identity is acquired and how it may be lost. In international law, the legal means to acquire nationality and formal membership in a nation are separated from the relationship between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Some nations domestically use the terms interchangeably, though by the 20th century, nationality had commonly come to mean the status of belonging to a particular nation with no regard to the type of governance which established a relationship between the nation and its people. In law, nationality describes the relationship of a national to the state under international law and citizenship describes the relationship of a citizen within the state under domestic statutes. Different regulatory agencies monitor legal compliance for nationality and citizenship. A person in a country of which he or she is not a national is generally regarded by that country as a foreigner or alien. A person who has no recognised nationality to any jurisdiction is regarded as stateless.

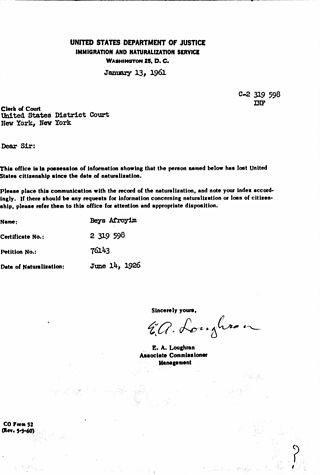

Denaturalization is the loss of citizenship against the will of the person concerned. Denaturalization is often applied to ethnic minorities and political dissidents. Denaturalization can be a penalty for actions considered criminal by the state, often only for errors in the naturalization process such as fraud. Since the 9/11 attacks, the denaturalization of people accused of terrorism has increased. Because of the right to nationality, recognized by multiple international treaties including Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, denaturalization is often considered a human rights violation.

Polish nationality law is based primarily on the principle of jus sanguinis. Children born to at least one Polish parent acquire Polish citizenship irrespective of place of birth. Besides other things, Polish citizenship entitles the person to a Polish passport.

Belarusian nationality law regulates the manner in which one acquires, or is eligible to acquire, Belarusian nationality, citizenship. Belarusian citizenship is membership in the political community of the Republic of Belarus.

Lithuanian nationality law operates on the jus sanguinus principle, whereby persons who have a claim to Lithuanian ancestry, either through parents, grandparents, great-grandparents may claim Lithuanian nationality. Citizenship may also be granted by naturalization. Naturalization requires a residency period, an examination in the Lithuanian language, examination results demonstrating familiarity with the Lithuanian Constitution, a demonstrated means of support, and an oath of loyalty. A right of return clause was included in the 1991 constitution for persons who left Lithuania after the Soviet occupation in 1940 and their descendants. Lithuanian citizens are also citizens of the European Union and thus enjoy rights of free movement and have the right to vote in elections for the European Parliament.

Non-citizens or aliens in Latvian law are individuals who are not citizens of Latvia or any other country, but who, in accordance with the Latvian law "Regarding the status of citizens of the former USSR who possess neither Latvian nor other citizenship," have the right to a non-citizen passport issued by the Latvian government as well as other specific rights. Approximately two thirds of them are ethnic Russians, followed by Belarusians, Ukrainians, Poles, and Lithuanians.

Estonian citizenship law details the conditions by which a person is a citizen of Estonia. The primary law currently governing these requirements is the Citizenship Act, which came into force on 1 April 1995.

Ukrainian nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds nationality of Ukraine. The primary law governing these requirements is the law "On Citizenship of Ukraine", which came into force on 1 March 2001.

The Latvian nationality law is based on the Citizenship Law of 1994. It is primarily based on the principles of jus sanguinis.

Russian citizenship law details the conditions by which a person holds citizenship of Russia. The primary law governing citizenship requirements is the federal law "On Citizenship of the Russian Federation", which came into force on 1 July 2002.

Armenian nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Armenia, as amended; the Citizenship Law of Armenia and its revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, an Armenian national. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. Some countries use the terms nationality and citizenship as synonyms, despite their legal distinction and the fact that they are regulated by different governmental administrative bodies. In Armenia, colloquially the term for citizenship, "քաղաքացիություն", refers to both belonging and rights within the nation and the term for nationality, "ազգություն", refers to ethnic identity. Armenian nationality is typically obtained under the principal of jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth to parents with Armenian nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

Azerbaijani nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Azerbaijan, as amended; the Citizenship Law of Azerbaijan and its revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, an Azerbaijani national.

Thai nationality law includes principles of both jus sanguinis and jus soli. Thailand's first Nationality Act was passed in 1913. The most recent law dates to 2008.

Loss of citizenship, also referred to as loss of nationality, is the event of ceasing to be a citizen of a country under the nationality law of that country.

The nationality law of Bosnia and Herzegovina governs the acquisition, transmission and loss of citizenship of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Regulated under the framework of the Law on Citizenship of Bosnia and Herzegovina, it is based primarily on the principle of jus sanguinis.

San Marino nationality law is contained in the provisions of the Law on Citizenship (2000) which was amended in 2004 and 2016 and in the relevant provisions of the San Marino Constitution. A person may be a citizen of San Marino through birth, descent or through naturalisation.

Mozambican nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Mozambique, as amended; the Nationality Law and Nationality Regulation, and their revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Mozambique. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. Mozambican nationality is typically obtained under the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in the territory, or jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth in Mozambique or abroad to parents with Mozambican nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Sandifer, Durward V. (October 1936). "Soviet Citizenship". The American Journal of International Law . 30 (4): 614–631. doi:10.2307/2191124. JSTOR 2191124. S2CID 246003387.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Alexopolous, Golfo (Summer 2006). "Soviet Citizenship, More or Less: Rights, Emotions, and States of Civic Belonging". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 7 (3): 487–528. doi:10.1353/kri.2006.0030. S2CID 144846348.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Taracouzio, Timothy Andrew (1935). The Soviet union and international law; a study based on the legislation, treaties and foreign relations of the Union of socialist soviet republics. Macmillan. pp. 379–382.

- 1 2 Shevel, Oxana (April 2013). "Country Report: Ukraine" (PDF). European University Institute. pp. 3–4. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "Laws Concerning Nationality" (PDF). United Nations Legislative Series. United Nations. 1954. pp. xiv–xv. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 Ginsburgs, George (1983). The Citizenship Law of the USSR. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 11–14, 37, 71–72. ISBN 978-94-015-1184-1.

- 1 2 3 Makaryan, Shushanik (March 30, 2006). "Trends in Citizenship Policies of the 15 Former Soviet Union Republics: Conforming the World Culture or Following National Identity?" (PDF). University of California, Irvine School of Social Sciences. pp. 3–4. S2CID 31169767 . Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ↑ Plender, Richard (1988). International Migration Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-247-3604-1.