The right of abode is an individual's freedom from immigration control in a particular country. A person who has the right of abode in a country does not need permission from the government to enter the country and can live and work there without restriction, and is immune from removal and deportation.

The primary law governing nationality of Ireland is the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act, 1956, which came into force on 17 July 1956. Ireland is a member state of the European Union (EU), and all Irish nationals are EU citizens. They are entitled to free movement rights in EU and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries, and may vote in elections to the European Parliament. Irish citizens also have the right to live, work, and enter and exit the United Kingdom freely, and are the only EU citizens permitted to do this due to the common travel area between the UK and Ireland.

Finnish nationality law details the conditions by which an individual is a national of Finland. The primary law governing these requirements is the Nationality Act, which came into force on 1 June 2003. Finland is a member state of the European Union (EU) and all Finnish nationals are EU citizens. They are entitled to free movement rights in EU and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries and may vote in elections to the European Parliament.

German nationality law details the conditions by which an individual is a national of Germany. The primary law governing these requirements is the Nationality Act, which came into force on 1 January 1914. Germany is a member state of the European Union (EU) and all German nationals are EU citizens. They have automatic and permanent permission to live and work in any EU or European Free Trade Association (EFTA) country and may vote in elections to the European Parliament.

Dutch nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds Dutch nationality. The primary law governing these requirements is the Dutch Nationality Act, which came into force on 1 January 1985. Regulations apply to the entire Kingdom of the Netherlands, which includes the country of the Netherlands itself, Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten.

Swedish nationality law determines entitlement to Swedish citizenship. Citizenship of Sweden is based primarily on the principle of jus sanguinis. In other words, citizenship is conferred primarily by birth to a Swedish parent, irrespective of place of birth.

The primary law governing nationality of Portugal is the Nationality Act, which came into force on 3 October 1981. Portugal is a member state of the European Union (EU) and all Portuguese nationals are EU citizens. They are entitled to free movement rights in EU and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries and may vote in elections to the European Parliament.

Maltese nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of Malta. The primary law governing nationality regulations is the Maltese Citizenship Act, which came into force on 21 September 1964. Malta is a member state of the European Union (EU) and all Maltese nationals are EU citizens. They have automatic and permanent permission to live and work in any EU or European Free Trade Association (EFTA) country and may vote in elections to the European Parliament.

Norwegian nationality law details the conditions by which an individual is a national of Norway. The primary law governing these requirements is the Norwegian Nationality Act, which came into force on 1 September 2006. Norway is a member state of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and the Schengen Area. All Norwegian nationals have automatic and permanent permission to live and work in any European Union (EU) or EFTA country.

The Citizens' Rights Directive 2004/38/EC sets out the conditions for the exercise of the right of free movement for citizens of the European Economic Area (EEA), which includes the member states of the European Union (EU) and the three European Free Trade Association (EFTA) members Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein. Switzerland, which is a member of EFTA but not of the EEA, is not bound by the Directive but rather has a separate multilateral sectoral agreement on free movement with the EU and its member states.

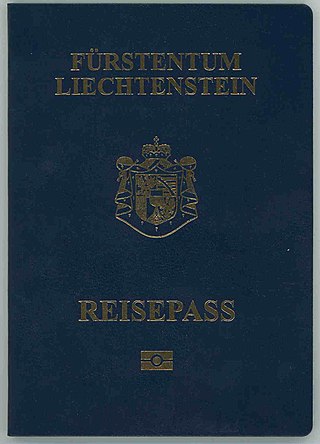

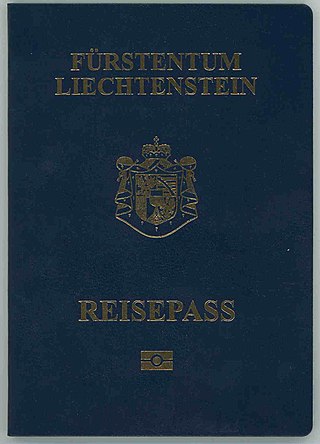

Liechtenstein passports are issued to nationals of Liechtenstein for the purpose of international travel. Beside serving as proof of Liechtenstein citizenship, they facilitate the process of securing assistance from Liechtenstein consular officials abroad.

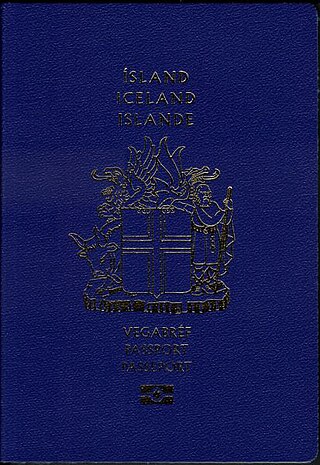

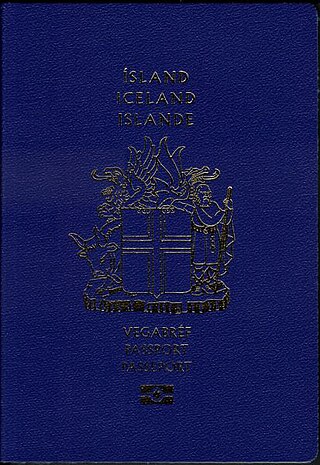

Icelandic passports are issued to citizens of Iceland for the purpose of international travel. Beside serving as proof of Icelandic citizenship, they facilitate the process of securing assistance from Icelandic consular officials abroad.

Cypriot nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of Cyprus. The primary law governing nationality regulations is the Republic of Cyprus Citizenship Law, 1967, which came into force on 28 July 1967. Regulations apply to the entire island of Cyprus, which includes the Republic of Cyprus itself and Northern Cyprus, a breakaway region that is diplomatically recognised only by Turkey as the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC).

Bulgarian nationality law is governed by the Constitution of Bulgaria of 1991 and the citizenship law of 1999.

Danish nationality law is governed by the Constitutional Act and the Consolidated Act of Danish Nationality. Danish nationality can be acquired in one of the following ways:

The primary law governing nationality in the United Kingdom is the British Nationality Act 1981, which came into force on 1 January 1983. Regulations apply to the British Islands, which include the UK itself and the Crown dependencies ; and the 14 British Overseas Territories.

Pakistani nationality law details the conditions by which a person is a national of Pakistan. The primary law governing these requirements is the Pakistan Citizenship Act, 1951, which came into force on 13 April 1951.

Multiple citizenship is a person's legal status in which a person is at the same time recognized by more than one country under its nationality and citizenship law as a national or citizen of that country. There is no international convention that determines the nationality or citizenship status of a person, which is consequently determined exclusively under national laws, that often conflict with each other, thus allowing for multiple citizenship situations to arise.

National identity cards are identity documents issued to citizens of most European Union and European Economic Area (EEA) member states, with the exception of Denmark and Ireland. As a new common identity card model replaced the various formats in use from 2 August 2021, recently issued ID cards are harmonized across the EEA, while older ID cards are currently being phased out according to Regulation (EU) 2019/1157.

Liechtensteiner nationality law details the conditions by which an individual is a national of Liechtenstein. The primary law governing these requirements is the Law on the Acquisition and Loss of Citizenship, which came into force on 4 January 1934.