Fable is a literary genre defined as a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are anthropomorphized, and that illustrates or leads to a particular moral lesson, which may at the end be added explicitly as a concise maxim or saying.

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

The Fox and the Grapes is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 15 in the Perry Index. The narration is concise and subsequent retellings have often been equally so. The story concerns a fox that tries to eat grapes from a vine but cannot reach them. Rather than admit defeat, he states they are undesirable. The expression "sour grapes" originated from this fable.

The lion's share is an idiomatic expression which now refers to the major share of something. The phrase derives from the plot of a number of fables ascribed to Aesop and is used here as their generic title. There are two main types of story, which exist in several different versions. Other fables exist in the East that feature division of prey in such a way that the divider gains the greater part - or even the whole. In English the phrase used in the sense of nearly all only appeared at the end of the 18th century; the French equivalent, le partage du lion, is recorded from the start of that century, following La Fontaine's version of the fable.

The Monkey and the Cat is best known as a fable adapted by Jean de La Fontaine under the title Le Singe et le Chat that appeared in the second collection of his Fables in 1679 (IX.17). It is the source of popular idioms in both English and French, with the general meaning of being the dupe of another.

The Lion and the Mouse is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 150 in the Perry Index. There are also Eastern variants of the story, all of which demonstrate mutual dependence regardless of size or status. In the Renaissance the fable was provided with a sequel condemning social ambition.

The Dog and Its Reflection is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 133 in the Perry Index. The Greek language original was retold in Latin and in this way was spread across Europe, teaching the lesson to be contented with what one has and not to relinquish substance for shadow. There also exist Indian variants of the story. The morals at the end of the fable have provided both English and French with proverbs and the story has been applied to a variety of social situations.

The Fox and the Crow is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 124 in the Perry Index. There are early Latin and Greek versions and the fable may even have been portrayed on an ancient Greek vase. The story is used as a warning against listening to flattery.

The Tortoise and the Birds is a fable of probable folk origin, early versions of which are found in both India and Greece. There are also African variants. The moral lessons to be learned from these differ and depend on the context in which they are told.

The Bear and the Travelers is a fable attributed to Aesop and is number 65 in the Perry Index. It was expanded and given a new meaning in mediaeval times.

The Milkmaid and Her Pail is a folktale of Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 1430 about interrupted daydreams of wealth and fame. Ancient tales of this type exist in the East but Western variants are not found before the Middle Ages. It was only in the 18th century that the story about the daydreaming milkmaid began to be attributed to Aesop, although it was included in none of the main collections and does not appear in the Perry Index. In more recent times, the fable has been variously treated by artists and set by musicians.

The Lion, the Bear and the Fox is one of Aesop's Fables that is numbered 147 in the Perry Index. There are similar story types of both eastern and western origin in which two disputants lose the object of their dispute to a third.

The Wolf and the Crane is a fable attributed to Aesop that has several eastern analogues. Similar stories have a lion instead of a wolf, and a stork, heron or partridge takes the place of the crane.

The Ass in the Lion's Skin is one of Aesop's Fables, of which there are two distinct versions. There are also several Eastern variants, and the story's interpretation varies accordingly.

The Wolf and the Lamb is a well-known fable of Aesop and is numbered 155 in the Perry Index. There are several variant stories of tyrannical injustice in which a victim is falsely accused and killed despite a reasonable defence.

The Fox and the Cat is an ancient fable, with both Eastern and Western analogues involving different animals, that addresses the difference between resourceful expediency and a master stratagem. Included in collections of Aesop's fables since the start of printing in Europe, it is number 605 in the Perry Index. In the basic story a cat and a fox discuss how many tricks and dodges they have. The fox boasts that he has many; the cat confesses to having only one. When hunters arrive with their dogs, the cat climbs a tree, but the fox thinks of many ways without acting and is caught by the hounds. Many morals have been drawn from the fable's presentations through history and, as Isaiah Berlin's use of it in his essay "The Hedgehog and the Fox" shows, it continues to be interpreted anew.

The Two Pots is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 378 in the Perry Index. The fable may stem from proverbial sources.

Jean de La Fontaine collected fables from a wide variety of sources, both Western and Eastern, and adapted them into French free verse. They were issued under the general title of Fables in several volumes from 1668 to 1694 and are considered classics of French literature. Humorous, nuanced and ironical, they were originally aimed at adults but then entered the educational system and were required learning for school children.

The Frog and the Mouse is one of Aesop's Fables and exists in several versions. It is numbered 384 in the Perry Index. There are also Eastern versions of uncertain origin which are classified as Aarne-Thompson type 278, concerning unnatural relationships. The stories make the point that the treacherous are destroyed by their own actions.

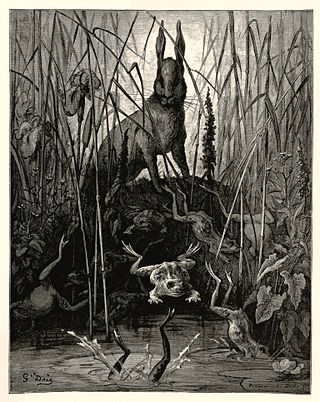

Hares are proverbially timid and a number of fables have been based on this behaviour. The best known, often titled "The Hares and the Frogs", appears among Aesop's Fables and is numbered 138 in the Perry Index. As well as having an Asian analogue, there have been variant versions over the centuries.