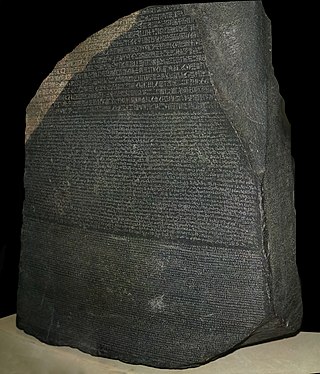

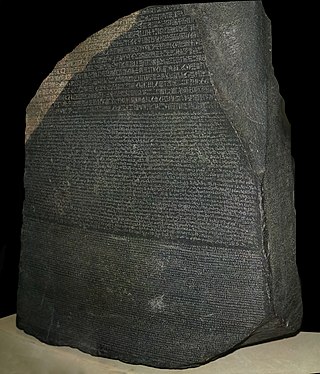

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle texts are in Ancient Egyptian using hieroglyphic and Demotic scripts respectively, while the bottom is in Ancient Greek. The decree has only minor differences between the three versions, making the Rosetta Stone key to deciphering the Egyptian scripts.

Jean-François Champollion, also known as Champollion le jeune, was a French philologist and orientalist, known primarily as the decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphs and a founding figure in the field of Egyptology. Partially raised by his brother, the scholar Jacques Joseph Champollion-Figeac, Champollion was a child prodigy in philology, giving his first public paper on the decipherment of Demotic in his mid-teens. As a young man he was renowned in scientific circles, and spoke Coptic, Ancient Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Arabic.

Étienne Marc Quatremère was a French Orientalist.

Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat was a French sinologist best known as the first Chair of Sinology at the Collège de France. Rémusat studied medicine as a young man, but his discovery of a Chinese herbal treatise enamored him with the Chinese language, and he spent five years teaching himself to read it. After publishing several well-received articles on Chinese topics, a chair in Chinese was created at the Collège de France in 1814 and Rémusat was placed in it.

Pierre Amédée Emilien Probe Jaubert was a French diplomat, academic, orientalist, translator, politician, and traveler. He was Napoleon's "favourite orientalist adviser and dragoman".

Joseph Héliodore Sagesse Vertu Garcin de Tassy was a French orientalist.

Johan David Åkerblad was a Swedish diplomat and orientalist.

The writing systems used in ancient Egypt were deciphered in the early nineteenth century through the work of several European scholars, especially Jean-François Champollion and Thomas Young. Ancient Egyptian forms of writing, which included the hieroglyphic, hieratic and demotic scripts, ceased to be understood in the fourth and fifth centuries AD, as the Coptic alphabet was increasingly used in their place. Later generations' knowledge of the older scripts was based on the work of Greek and Roman authors whose understanding was faulty. It was thus widely believed that Egyptian scripts were exclusively ideographic, representing ideas rather than sounds, and even that hieroglyphs were an esoteric, mystical script rather than a means of recording a spoken language. Some attempts at decipherment by Islamic and European scholars in the Middle Ages and early modern times acknowledged the script might have a phonetic component, but perception of hieroglyphs as purely ideographic hampered efforts to understand them as late as the eighteenth century.

The Société Asiatique is a French learned society dedicated to the study of Asia. It was founded in 1822 with the mission of developing and diffusing knowledge of Asia. Its boundaries of geographic interest are broad, ranging from the Maghreb to the Far East. The society publishes the Journal asiatique. At present the society has about 700 members in France and abroad; its library contains over 90,000 volumes.

Jean Paul Louis François Édouard Leuge-Dulaurier was a French Orientalist, Armenian studies scholar and Egyptologist.

Louis-Mathieu Langlès was a French academic, philologist, linguist, translator, author, librarian and orientalist. He was the conservator of the oriental manuscripts at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Napoleonic France and he held the same position at the renamed Bibliothèque du Roi after the fall of the empire.

Marcel Samuel Raphaël Cohen was a French linguist. He was an important scholar of Semitic languages and especially of Ethiopian languages. He studied the French language and contributed much to general linguistics.

Francesco Salvolini was a scholar of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs who worked with Jean-François Champollion on deciphering hieroglyphs near the end of the latter's life. He is known to have been in possession of some of Champollion's manuscripts and to have used them as a basis for his own subsequent publications on the subject, claiming the work as his own.

Antoine-Pierre-Louis Bazin, or A. P. L. Bazin was a French sinologist born in Saint-Brice-sous-Forêt. He was the brother of dermatologist Pierre-Antoine-Ernest Bazin (1807-1878).

Anton ZakhūrRafa'il known in France as Raphaël de Monachis was an Egyptian-born monk of Syrian ancestry, known for his orientalist studies and for being one of Jean-François Champollion's language teachers. He was born in Cairo to a Syrian-Melkite family. He studied at the Greek seminary in Rome and took his vows at the Basilian Monastery of the Saviour in Sidon where he remained from 1789 to 1794 when he returned to Egypt. During Napoleon's campaign in Egypt he served as Napoleon's personal interpreter. In 1803 he traveled to France where after visiting Joseph Fourier in Grenoble, he traveled to Paris to give important documents to the French government. He was appointed as adjunct professor of Arabic language at the École des Langues Orientales. Among his students there was Champollion, to whom he taught colloquial Arabic and Coptic. He was also the single Arab member of the French Institut d'Égypte. His colleague there, Silvestre de Sacy, who taught literary Arabic was strongly opposed to having a second professor of Arabic at the School of Oriental languages, considering it a personal offense. In 1803 he participated in the Coronation of Napoleon I and was depicted in Jacques-Louis David's famous painting.

Abel Jean Baptiste Michel Pavet de Courteille was a 19th-century French orientalist, who specialized in the study of Turkic languages.

Louis-Jacques Bresnier was a 19th-century French orientalist. He died in Algiers of a stroke while entering the library where he would give his lesson.

Maurice Gaudefroy-Demombynes was a French Arabist, a specialist in Islam and the history of religions.

Jean Deny was a French grammarian, specialist of oriental languages.

Grammaire égyptienne is a grammar reference book by the French Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion, published posthumously in France in 1836. Its full title, the Grammaire égyptienne ou Principes généraux de l'écriture sacrée égyptienne appliqué à la présentation de la langue parlée means Egyptian Grammar or General Principles of Egyptian Sacred Writing Applied to the Presentation of the Spoken Language.