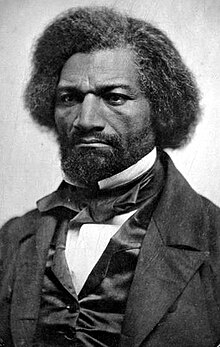

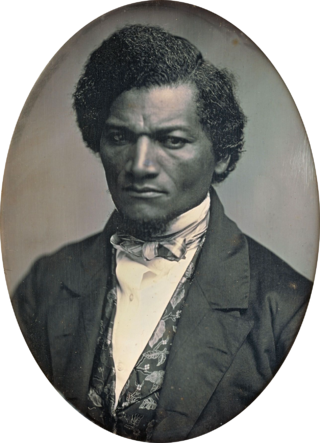

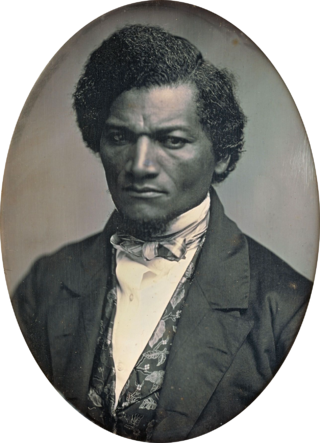

Frederick Douglass was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. He became the most important leader of the movement for African-American civil rights in the 19th century.

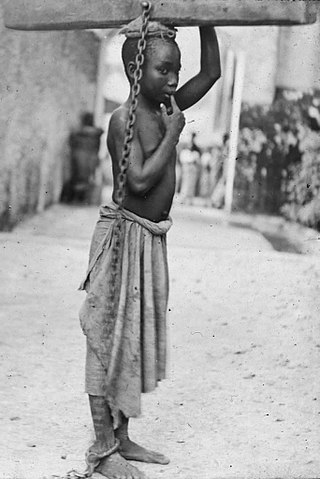

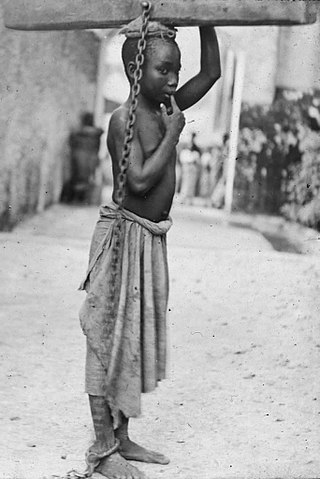

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) was an abolitionist society in the United States. AASS formed in 1833 in response to the nullification crisis and the failures of existing anti-slavery organizations, such as the American Colonization Society. AASS formally dissolved in 1870.

The origins of the American Civil War were rooted in the desire of the Southern states to preserve the institution of slavery. Historians in the 21st century overwhelmingly agree on the centrality of slavery in the conflict. They disagree on which aspects were most important, and on the North's reasons for refusing to allow the Southern states to secede. The pseudo-historical Lost Cause ideology denies that slavery was the principal cause of the secession, a view disproven by historical evidence, notably some of the seceding states' own secession documents. After leaving the Union, Mississippi issued a declaration stating, "Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world."

The Three-fifths Compromise was an agreement reached during the 1787 United States Constitutional Convention over the inclusion of slaves in a state's total population. This count would determine: the number of seats in the House of Representatives; the number of electoral votes each state would be allocated; and how much money the states would pay in taxes. Slave holding states wanted their entire population to be counted to determine the number of Representatives those states could elect and send to Congress. Free states wanted to exclude the counting of slave populations in slave states, since those slaves had no voting rights. A compromise was struck to resolve this impasse. The compromise counted three-fifths of each state's slave population toward that state's total population for the purpose of apportioning the House of Representatives, effectively giving the Southern states more power in the House relative to the Northern states. It also gave slaveholders similarly enlarged powers in Southern legislatures; this was an issue in the secession of West Virginia from Virginia in 1863. Free black people and indentured servants were not subject to the compromise, and each was counted as one full person for representation.

The Liberator (1831–1865) was a weekly abolitionist newspaper, printed and published in Boston by William Lloyd Garrison and, through 1839, by Isaac Knapp. Religious rather than political, it appealed to the moral conscience of its readers, urging them to demand immediate freeing of the slaves ("immediatism"). It also promoted women's rights, an issue that split the American abolitionist movement. Despite its modest circulation of 3,000, it had prominent and influential readers, including all the abolitionist leaders, among them Frederick Douglass, Beriah Green, Arthur and Lewis Tappan, and Alfred Niger. It frequently printed or reprinted letters, reports, sermons, and news stories relating to American slavery, becoming a sort of community bulletin board for the new abolitionist movement that Garrison helped foster.

Joshua Reed Giddings was an American attorney, politician and abolitionist. He represented Northeast Ohio in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1838 to 1859. He was at first a member of the Whig Party and was later a Republican, helping found the party.

The North Star was a nineteenth-century anti-slavery newspaper published from the Talman Building in Rochester, New York, by abolitionists Martin Delany and Frederick Douglass. The paper commenced publication on December 3, 1847, and ceased as The North Star in June 1851, when it merged with Gerrit Smith's Liberty Party Paper to form Frederick Douglass' Paper. At the time of the Civil War, it was Douglass' Monthly.

The Slave Power, or Slavocracy, referred to the perceived political power held by American slaveholders in the federal government of the United States during the Antebellum period. Antislavery campaigners charged that this small group of wealthy slaveholders had seized political control of their states and were trying to take over the federal government illegitimately to expand and protect slavery. The claim was later used by the Republican Party that formed in 1854–55 to oppose the expansion of slavery.

The Missouri Compromise was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state and declared a policy of prohibiting slavery in the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36°30′ parallel. The 16th United States Congress passed the legislation on March 3, 1820, and President James Monroe signed it on March 6, 1820.

James Oakes is an American historian, and is a Distinguished Professor of History and Graduate School Humanities Professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York where he teaches courses on the American Civil War and Reconstruction, Slavery, the Old South, Abolitionism, and U.S. and World History. He taught previously at Princeton University and Northwestern University.

The Heroic Slave, a Heartwarming Narrative of the Adventures of Madison Washington, in Pursuit of Liberty is a short piece of fiction, or novella, written by abolitionist Frederick Douglass, at the time a fugitive slave based in Boston. When the Rochester Ladies' Anti Slavery Society asked Douglass for a short story to go in their collection, Autographs for Freedom, Douglass responded with The Heroic Slave. The novella, published in 1852 by John P. Jewett and Company, was Douglass's first and only published work of fiction.

The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1845) was a book by American abolitionist Lysander Spooner arguing that the United States Constitution prohibited slavery. This view was contrary to that of William Lloyd Garrison who opposed the Constitution on the grounds that it was pro-slavery. In the book, Spooner shows that none of the state governments of the slave states specifically authorized slavery, that the U.S. Constitution contains several clauses that are inconsistent with slavery, that slavery was a violation of natural law, and that the intentions of the Constitutional Convention have no legal bearing on the document they created. Thus, Spooner's position is one that employs original meaning-styled textualism and rejects original intent-styled originalism.

The Liberty Party was an abolitionist political party in the United States before the American Civil War. The party experienced its greatest activity during the 1840s, while remnants persisted as late as 1860. It supported James G. Birney in the presidential elections of 1840 and 1844. Others who attained prominence as leaders of the Liberty Party included Gerrit Smith, Salmon P. Chase, Henry Highland Garnet, Henry Bibb, and William Goodell. They attempted to work within the federal system created by the United States Constitution to diminish the political influence of the Slave Power and advance the cause of universal emancipation and an integrated, egalitarian society.

In the United States, abolitionism, the movement that sought to end slavery in the country, was active from the colonial era until the American Civil War, the end of which brought about the abolition of American slavery, except as punishment for a crime, through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

National conventions of the Free Soil and Liberty parties met in 1847 and 1848 to nominate candidates for president and vice president in advance of the 1848 United States presidential election. These assemblies resulted in the creation of the national Free Soil Party, a union of political abolitionists with antislavery Conscience Whigs and Barnburner Democrats to oppose the westward extension of slavery into the U.S. territories. Former President Martin Van Buren was nominated for president by the Free Soil National Convention that met at Buffalo, New York on August 9, 1848; Charles Francis Adams Sr. was nominated for vice president. Van Buren and Adams received 291,409 popular votes in the national election, almost all from the free states; his popularity among northern Democrats was great enough to deny his Democratic rival, Lewis Cass, the crucial state of New York, throwing the state and the election to Whig Zachary Taylor.

"What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" was a speech delivered by Frederick Douglass on July 5, 1852, at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. In the address, Douglass states that positive statements about perceived American values, such as liberty, citizenship, and freedom, were an offense to the enslaved population of the United States because they lacked those rights. Douglass referred not only to the captivity of enslaved people, but to the merciless exploitation and the cruelty and torture that slaves were subjected to in the United States.

James Cropper (1773–1840) was an English businessman and philanthropist, known as an abolitionist who made a major contribution to the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833.

Although the United States Constitution has never contained the words "slave" or "slavery" within its text, it dealt directly with American slavery in at least five of its provisions and indirectly protected the institution elsewhere in the document.

The Radical Abolitionist Party was a political party formed by abolitionists in the United States in the decade preceding the American Civil War as part of a reaction to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The party was formed following their first convention in 1855 and lasted until the end of the decade. The Radical Abolition Party was distinct from other contemporary political groups of the time for their aims to immediately eliminate the institution of slavery and advocate for full citizenship rights for African Americans. They also advocated for other marginalized groups' rights, such as women and Native Americans. Many prominent black and white abolitionists were founders and members including Frederick Douglass, James McCune Smith, William Goodell, Gerrit Smith, and John Brown. It did not elect a candidate to office, rather made significant contributions to political discourse and helped shape the Republican Party's future platform on slavery.