Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems. Although usually contrasted with social anarchism, both individualist and social anarchism have influenced each other. Some anarcho-capitalists claim anarcho-capitalism is part of the individualist anarchist tradition, while others disagree and claim individualist anarchism is only part of the socialist movement and part of the libertarian socialist tradition. Economically, while European individualist anarchists are pluralists who advocate anarchism without adjectives and synthesis anarchism, ranging from anarcho-communist to mutualist economic types, most American individualist anarchists of the 19th century advocated mutualism, a libertarian socialist form of market socialism, or a free-market socialist form of classical economics. Individualist anarchists are opposed to property that violates the entitlement theory of justice, that is, gives privilege due to unjust acquisition or exchange, and thus is exploitative, seeking to "destroy the tyranny of capital,—that is, of property" by mutual credit.

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and advocating that the interests of the individual should gain precedence over the state or a social group, while opposing external interference upon one's own interests by society or institutions such as the government. Individualism makes the individual its focus, and so starts "with the fundamental premise that the human individual is of primary importance in the struggle for liberation".

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and social theories and movements associated with the implementation of such systems. Social ownership can take various forms, including public, community, collective, cooperative, or employee. As one of the main ideologies on the political spectrum, socialism is considered the standard left wing ideology in most countries of the world. Types of socialism vary based on the role of markets and planning in resource allocation, and the structure of management in organizations.

George Woodcock was a Canadian writer of political biography and history, an anarchist thinker, a philosopher, an essayist and literary critic. He was also a poet and published several volumes of travel writing. In 1959 he was the founding editor of the journal Canadian Literature which was the first academic journal specifically dedicated to Canadian writing. He is most commonly known outside Canada for his book Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements (1962).

Self-ownership, also known as sovereignty of the individual or individual sovereignty, is the concept of property in one's own person, expressed as the moral or natural right of a person to have bodily integrity and be the exclusive controller of one's own body and life. Self-ownership is a central idea in several political philosophies that emphasize individualism, such as libertarianism, liberalism, and anarchism.

According to different scholars, the history of anarchism either goes back to ancient and prehistoric ideologies and social structures, or begins in the 19th century as a formal movement. As scholars and anarchist philosophers have held a range of views on what anarchism means, it is difficult to outline its history unambiguously. Some feel anarchism is a distinct, well-defined movement stemming from 19th-century class conflict, while others identify anarchist traits long before the earliest civilisations existed.

The nature of capitalism is criticized by left-wing anarchists, who reject hierarchy and advocate stateless societies based on non-hierarchical voluntary associations. Anarchism is generally defined as the libertarian philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful as well as opposing authoritarianism, illegitimate authority and hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations. Capitalism is generally considered by scholars to be an economic system that includes private ownership of the means of production, creation of goods or services for profit or income, the accumulation of capital, competitive markets, voluntary exchange and wage labor, which have generally been opposed by most anarchists historically. Since capitalism is variously defined by sources and there is no general consensus among scholars on the definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category, the designation is applied to a variety of historical cases, varying in time, geography, politics and culture.

Anarchism has long had an association with the arts, particularly with visual art, music and literature. This can be dated back to the start of anarchism as a named political concept, and the writings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon on the French realist painter Gustave Courbet. In an essay on Courbet of 1857 Proudhon had set out a principle for art, which he saw in the work of Courbet, that it should show the real lives of the working classes and the injustices working people face at the hands of the bourgeoisie.

Joseph Déjacque was a French political journalist and poet. A house painter by trade, during the 1840s, he became involved in the French labour movement and taught himself how to write poetry. He was an active participant in the French Revolution of 1848, fighting on the barricades during the June Days uprising, for which he was arrested and imprisoned. He quickly became a target for political repression by Louis Napoleon Bonaparte's government, which imprisoned him for his poetry and forced him to flee into exile. His experiences radicalised him towards anarchism and he regularly criticised republican politicians for their anti-worker sentiment.

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought and anti-capitalist market socialist economic theory that advocates for workers' control of the means of production, a market economy made up of individual artisans and workers' cooperatives, and occupation and use property rights. As proponents of the labour theory of value and labour theory of property, mutualists oppose all forms of economic rent, profit and non-nominal interest, which they see as relying on the exploitation of labour. Mutualists seek to construct an economy without capital accumulation or concentration of land ownership. They also encourage the establishment of workers' self-management, which they propose could be supported through the issuance of mutual credit by mutual banks, with the aim of creating a federal society.

Individualist anarchism in the United States was strongly influenced by Benjamin Tucker, Josiah Warren, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Lysander Spooner, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Max Stirner, Herbert Spencer and Henry David Thoreau. Other important individualist anarchists in the United States were Stephen Pearl Andrews, William Batchelder Greene, Ezra Heywood, M. E. Lazarus, John Beverley Robinson, James L. Walker, Joseph Labadie, Steven Byington and Laurance Labadie.

Individualist anarchism in Europe proceeded from the roots laid by William Godwin and soon expanded and diversified through Europe, incorporating influences from individualist anarchism in the United States. Individualist anarchism is a tradition of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual and his or her will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems. While most American individualist anarchists advocate mutualism, a libertarian socialist form of market socialism, or a free-market socialist form of classical economics, European individualist anarchists are pluralists who advocate anarchism without adjectives and synthesis anarchism, ranging from anarcho-communist to mutualist economic types.

Major anarchist thinkers, past and present, have generally supported women's equality. Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, viewing sexual freedom as an expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights. In New York's Greenwich Village, "bohemian" feminists and socialists advocated self-realisation and pleasure for both men and women. In Europe and North America, the free love movement combined ideas revived from utopian socialism with anarchism and feminism to attack the "hypocritical" sexual morality of the Victorian era.

Types of socialism include a range of economic and social systems characterised by social ownership and democratic control of the means of production and organizational self-management of enterprises as well as the political theories and movements associated with socialism. Social ownership may refer to forms of public, collective or cooperative ownership, or to citizen ownership of equity in which surplus value goes to the working class and hence society as a whole. There are many varieties of socialism and no single definition encapsulates all of them, but social ownership is the common element shared by its various forms Socialists disagree about the degree to which social control or regulation of the economy is necessary, how far society should intervene, and whether government, particularly existing government, is the correct vehicle for change.

Anarchism in Romania developed in the 1880s within the larger Romanian socialist movement and it had a small following throughout all the existence of the Kingdom of Romania. Social anarchism was initially propagated by the Revista Ideei during the time of the Old Kingdom, but following the rise of Bolshevism, socialist tendencies were sidelined in favor of individualism and vegetarianism, which were the predominant anarchist tendencies in Romania during the 1920s and 1930s.

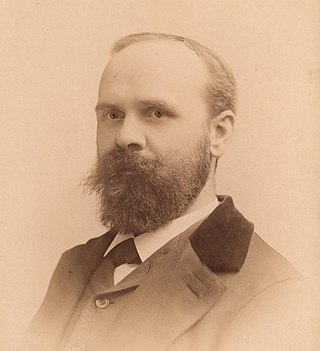

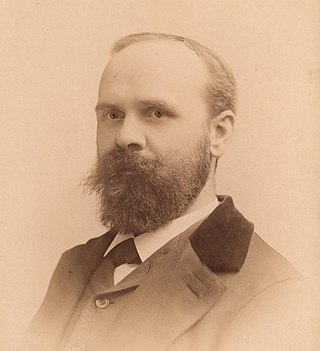

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker was an American individualist anarchist and self-identified socialist. Tucker was the editor and publisher of the American individualist anarchist periodical Liberty (1881–1908). Tucker described his form of anarchism as "consistent Manchesterism" and "unterrified Jeffersonianism".

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was a French socialist, politician, philosopher, and economist who founded mutualist philosophy and is considered by many to be the "father of anarchism". He was the first person to declare himself an anarchist, using that term, and is widely regarded as one of anarchism's most influential theorists. Proudhon became a member of the French Parliament after the Revolution of 1848, whereafter he referred to himself as a federalist. Proudhon described the liberty he pursued as "the synthesis of community and property". Some consider his mutualism to be part of individualist anarchism while others regard it to be part of social anarchism.

Market socialism is a type of economic system involving social ownership of the means of production within the framework of a market economy. Various models for such a system exist, usually involving cooperative enterprises and sometimes a mix that includes public or private enterprises. In contrast to the majority of historic socialist economies, which have substituted the market mechanism for some form of economic planning, market socialists wish to retain the use of supply and demand signals to guide the allocation of capital goods and the means of production. Under such a system, depending on whether socially owned firms are state-owned or operated as worker cooperatives, profits may variously be used to directly remunerate employees, accrue to society at large as the source of public finance, or be distributed amongst the population in a social dividend.

A classless society is a society in which no one is born into a social class like in a class society. Distinctions of wealth, income, education, culture, or social network might arise and would only be determined by individual experience and achievement in such a society. Thus, the concept posits not the absence of a social hierarchy but the uninheritability of class status. Helen Codere defines social class as a segment of the community, the members of which show a common social position in a hierarchical ranking. Codere suggest that a true class-organized society is one in which the hierarchy of prestige and social status is divisible into groups. Each group with its own social, economic, attitudinal and cultural characteristics, and each having differential degrees of power in community decision.

Anarchism and libertarianism, as broad political ideologies with manifold historical and contemporary meanings, have contested definitions. Their adherents have a pluralistic and overlapping tradition that makes precise definition of the political ideology difficult or impossible, compounded by a lack of common features, differing priorities of subgroups, lack of academic acceptance, and contentious historical usage.