Oscar Fingal O'Fflahertie Wills Wilde was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is best remembered for his epigrams and plays, his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, and his criminal conviction for gross indecency for homosexual acts.

The Importance of Being Earnest, A Trivial Comedy for Serious People is a play by Oscar Wilde. First performed on 14 February 1895 at the St James's Theatre in London, it is a farcical comedy in which the protagonists maintain fictitious personae to escape burdensome social obligations. Working within the social conventions of late Victorian London, the play's major themes are the triviality with which it treats institutions as serious as marriage and the resulting satire of Victorian ways. Some contemporary reviews praised the play's humour and the culmination of Wilde's artistic career, while others were cautious about its lack of social messages. Its high farce and witty dialogue have helped make The Importance of Being Earnest an enduringly popular play.

Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas, also known as Bosie Douglas, was an English poet and journalist, and a lover of Oscar Wilde. At Oxford he edited an undergraduate journal, The Spirit Lamp, that carried a homoerotic subtext, and met Wilde, starting a close but stormy relationship. Douglas's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, abhorred it and set out to humiliate Wilde, publicly accusing him of homosexuality. Wilde sued him for criminal libel, but some intimate notes were found and Wilde was later imprisoned. On his release, he briefly lived with Douglas in Naples, but they had separated by the time Wilde died in 1900. Douglas married a poet, Olive Custance, in 1902 and had a son, Raymond.

Aestheticism was an art movement in the late 19th century which valued the appearance of literature, music and the arts over their functions. According to Aestheticism, art should be produced to be beautiful, rather than to teach a lesson, create a parallel, or perform another didactic purpose, a sentiment best illustrated by the slogan "art for art's sake." Aestheticism originated in 1860s England with a radical group of artists and designers, including William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. It flourished in the 1870s and 1880s, gaining prominence and the support of notable writers such as Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde.

Jane Francesca Agnes, Lady Wilde was an Irish poet under the pen name Speranza and supporter of the nationalist movement. Lady Wilde had a special interest in Irish folktales, which she helped to gather and was the mother of Oscar Wilde and Willie Wilde.

Ernest Christopher Dowson was an English poet, novelist, and short-story writer who is often associated with the Decadent movement.

The Ballad of Reading Gaol is a poem by Oscar Wilde, written in exile in Berneval-le-Grand and Naples, after his release from Reading Gaol on 19 May 1897. Wilde had been incarcerated in Reading after being convicted of gross indecency with other men in 1895 and sentenced to two years' hard labour in prison.

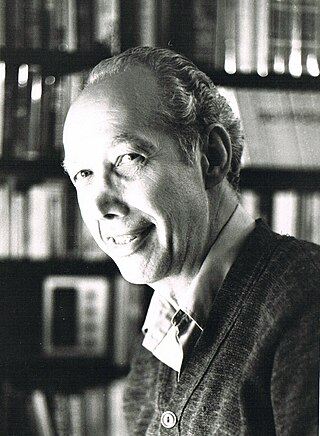

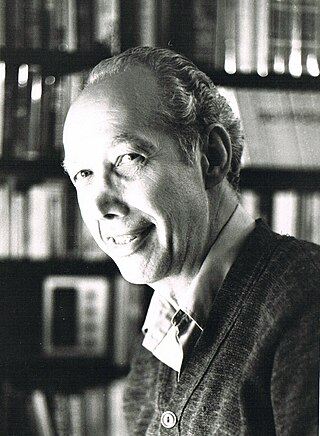

Richard David Ellmann, FBA was an American literary critic and biographer of the Irish writers James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, and William Butler Yeats. He won the U.S. National Book Award for Nonfiction for James Joyce (1959), which is one of the most acclaimed literary biographies of the 20th century. Its 1982 revised edition was similarly recognised with the award of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. Ellmann was a liberal humanist, and his academic work focused on the major modernist writers of the twentieth century.

À rebours is an 1884 novel by the French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans. The narrative centers on a single character: Jean des Esseintes, an eccentric, reclusive, ailing aesthete. The last scion of an aristocratic family, Des Esseintes loathes nineteenth-century bourgeois society and tries to retreat into an ideal artistic world of his own creation. The narrative is almost entirely a catalogue of the neurotic Des Esseintes's aesthetic tastes, musings on literature, painting, and religion, and hyperaesthesic sensory experiences.

Ada Esther Leverson was a British writer who is known for her friendship with Oscar Wilde and for her work as a witty novelist of the fin-de-siècle.

The Decadent movement was a late-19th-century artistic and literary movement, centered in Western Europe, that followed an aesthetic ideology of excess and artificiality.

John Evelyn Barlas, pseudonym Evelyn Douglas, was a Scottish poet and political activist of the late nineteenth century. He was a member of the decadent movement in literature, as well as a revolutionary socialist in politics. Eight books of his Swinburne-influenced verse were published between 1884 and 1893, including 1885's the Bloody Heart, 1887's Phantasmagoria: Dream-Fugues and 1889's Love Sonnets.

Karl E. Beckson was an American educator, scholar, and author of numerous articles and sixteen books on British literature, culture, and authors including Oscar Wilde, Arthur Symons, and Henry Harland. Of particular interest to him was the late 19th century Symbolist Movement and its influence on late 19th century and early 20th century authors including James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and Bernard Shaw. He co-authored, with Arthur Ganz, Literary Terms: A Dictionary, first published in 1960, and still available in its extensively revised 1990 third edition.

The Duchess of Padua is a five-act tragedy by Oscar Wilde, set in Padua and written in blank verse. It was written for the actress Mary Anderson in early 1883 while Wilde was in Paris. After she turned it down, it was abandoned until its first performance at the Broadway Theatre in New York City under the title Guido Ferranti on 26 January 1891, where it ran for three weeks. It has been rarely revived or studied.

De Profundis is a letter written by Oscar Wilde during his imprisonment in Reading Gaol, to "Bosie".

Hans Henning Otto Harry Baron von Voigt, best known by his nickname Alastair, was a German artist, composer, dancer, mime, poet, singer and translator.

Poems in Prose is the collective title of six prose poems published by Oscar Wilde in The Fortnightly Review. Derived from Wilde's many oral tales, these prose poems are the only six that were published by Wilde in his lifetime, and they include : "The Artist", "The Doer of Good", "The Disciple", "The Master", "The House of Judgment" and "The Teacher of Wisdom". Two of these prose poems, "The House of Judgment" and "The Disciple", had appeared earlier in The Spirit Lamp, an Oxford undergraduate magazine, on 17 February and 6 June 1893 respectively. A set of illustrations for the prose poems was completed by Wilde's friend and frequent illustrator, Charles Ricketts, who never published the pen-and-ink drawings in his lifetime. The set of prose poems was released in a privately printed chapbook in 1905.

Oscar Wilde's tomb is located in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, France. It took nine to ten months to complete by the sculptor Jacob Epstein, with an accompanying plinth by Charles Holden and an inscription carved by Joseph Cribb.

Charmides was Oscar Wilde's longest and one of his most controversial poems. It was first published in his 1881 collection Poems. The story is original to Wilde, though it takes some hints from Lucian of Samosata and other ancient writers; it tells a tale of transgressive sexual passion in a mythological setting in ancient Greece. Contemporary reviewers almost unanimously condemned it, but modern assessments vary widely. It has been called "an engaging piece of doggerel", a "comic masterpiece whose shock-value is comparable to that of Manet's Olympia and Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe", and "a Decadent poem par excellence" in which "[t]he illogicality of the plot and its deus-ex-machina resolution render the poem purely decorative". It is arguably the work in which Wilde first found his own poetic voice.

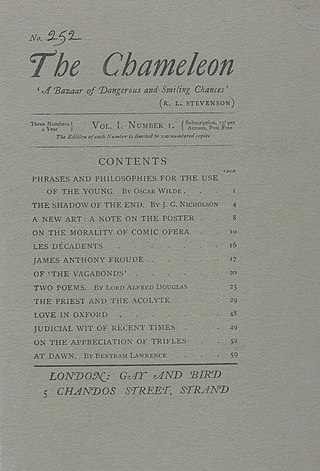

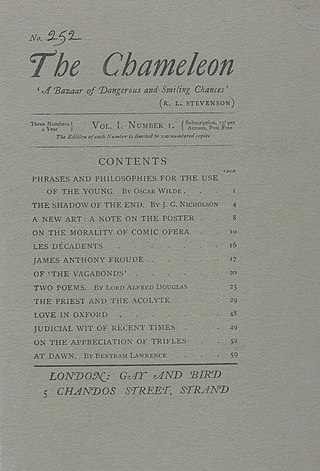

The Chameleon was a literary magazine edited by Oxford undergraduate John Francis Bloxam. Its first and only issue was published in December 1894. It featured several literary works from the Uranian tradition, concerning the love of adolescent boys.