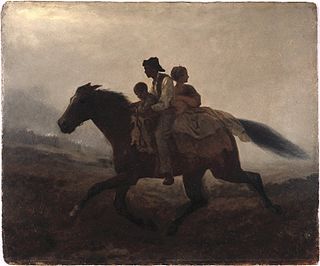

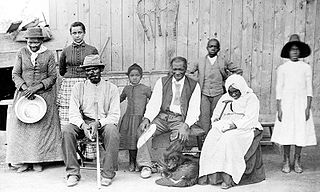

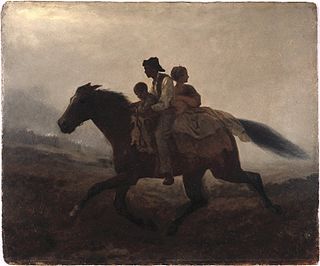

The Underground Railroad was a network of secret routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. The scheme was assisted by abolitionists and others sympathetic to the cause of the escapees. The enslaved who risked escape and those who aided them are also collectively referred to as the "Underground Railroad". Various other routes led to Mexico, where slavery had been abolished, and to islands in the Caribbean that were not part of the slave trade. An earlier escape route running south toward Florida, then a Spanish possession, existed from the late 17th century until approximately 1790. However, the network now generally known as the Underground Railroad was formed in the late 18th century. It ran north and grew steadily until the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln. One estimate suggests that, by 1850, 100,000 enslaved people had escaped via the network.

Harriet Tubman was an American abolitionist and political activist. Born into slavery, Tubman escaped and subsequently made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people, including family and friends, using the network of antislavery activists and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad. During the American Civil War, she served as an armed scout and spy for the Union Army. In her later years, Tubman was an activist in the movement for women's suffrage.

William Still was an African-American abolitionist based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a conductor on the Underground Railroad, businessman, writer, historian and civil rights activist. Before the American Civil War, Still was chairman of the Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. He directly aided fugitive slaves and also kept records of the people served in order to help families reunite.

In the United States, "fugitive slaves" were slaves who left their master and traveled without authorization. Generally, they tried to reach states or territories where slavery was banned, including Canada, or, until 1821, Spanish Florida. Most slave law tried to control slave travel by requiring them to carry official passes if traveling without a master with them.

Samuel Green was an slave, freedman, and minister of religion. A conductor of the Underground Railroad, he was tried and convicted in 1857 of possessing a copy of the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe following the Dover Eight incident. He received a ten-year sentence, and was pardoned by the Governor of Maryland Augustus Bradford in 1862, after he served five years.

Thomas Garrett was an American abolitionist and leader in the Underground Railroad movement before the American Civil War. For his fight against slavery, he was subject to threats, harassment and assaults. A $10,000 bounty was established for his capture, He was arrested and convicted in the Hawkins case. Over his life, he helped more than 2,500 African Americans escape slavery.

John Hunn was an American farmer and abolitionist who was a "station master" of the Underground Railroad in Delaware, the southernmost stationmaster and responsible for slaves escaping up the Delmarva Peninsula.

The Cyrus Gates Farmstead is located in Maine, New York. Cyrus Gates was a cartographer and map maker for New York State, as well as an abolitionist. The great granddaughter of Cyrus-Louise Gates-Gunsalus has stated that from 1848 until the end of slavery in the United States in 1865, the Cyrus Gates Farmstead was a station or stop on the Underground Railroad. Its owners, Cyrus and Arabella Gates, were outspoken abolitionists as well as active and vital members of their community. Historian Shirley L. Woodward states that through those years escaped slaves came through the Gates' station.

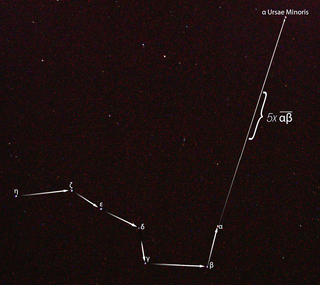

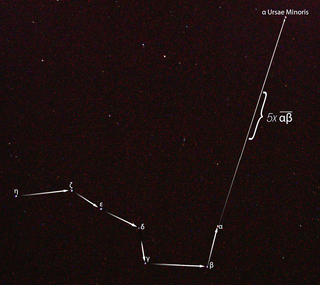

Songs of the Underground Railroad were spiritual and work songs used during the early-to-mid 19th century in the United States to encourage and convey coded information to escaping slaves as they moved along the various Underground Railroad routes. As it was illegal in most slave states to teach slaves to read or write, songs were used to communicate messages and directions about when, where, and how to escape, and warned of dangers and obstacles along the route.

Mary Edmonson (1832–1853) and Emily Edmonson (1835–1895), "two respectable young women of light complexion", were African Americans who became celebrities in the United States abolitionist movement after gaining their freedom from slavery. On April 15, 1848, they were among the 77 slaves who tried to escape from Washington, DC on the schooner The Pearl to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to freedom in New Jersey.

Freedom Crossing Monument is located on the bank of the Niagara River in Lewiston, New York, and honors the courage of fugitive slaves who sought a new life of freedom in Canada, and to the local volunteers who protected and helped them on their journey across the Niagara River. It was dedicated on October 14, 2009.

Raymond S. Lane, Jr., sculptor, created a series of hand-built clay sculptures about Harriet Tubman an Underground Railroad conductor, called “the Moses of the anti-slavery movement” by Cincinnati Enquirer reporter Allen Howard, was first displayed in 2002 in the Children's Learning Center of the Public Library of Hamilton County’s main building, 800 Vine St. in downtown Cincinnati. The clay works depict scenes in the life of the 19th century Underground Railroad heroine. The exhibits is called “Harriet Tubman's Experience in the Underground Railroad.” The sculptures currently are displayed at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Harriet, the Woman Called Moses is an opera in two acts composed by Thea Musgrave who also wrote the libretto which is loosely based on episodes in the life of the American abolitionist and former slave Harriet Tubman. The opera premiered on 1 March 1985 in Norfolk, Virginia, performed by Virginia Opera with subsequent broadcasts of the Virginia Opera production on National Public Radio and BBC Radio 3. Musgrave also wrote two shortened versions of the opera—The Story of Harriet Tubman and the concert work Remembering Harriet.

The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center is a visitors' center and history museum located on the grounds of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park in Church Creek, Maryland, in the United States. The state park is surrounded by the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, whose north side is bordered by the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park. Jointly created and managed by the National Park Service and Maryland Park Service, the visitor center opened on March 10, 2017.

Harriet Tubman's birthplace is in Dorchester County, Maryland. Araminta Ross, the daughter of Benjamin (Ben) and Harriet (Rit) Greene Ross, was born into slavery in 1822 in her father's cabin. It was located on the farm of Anthony Thompson at Peter's Neck, at the end of Harrisville Road, which is now part of the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge.

Harriet Tubman's family includes her birth family; her two husbands, John Tubman and Nelson Davis; and her adopted daughter Gertie Davis.

Dover Eight refers to a group of eight blacks who escaped their slaveholders of the Bucktown, Maryland area around March 8, 1857. They made it north to Dover, Delaware where they were turned in by Thomas Otwell and lured to the Dover jail with the intention of getting the $3,000 reward for the eight men. The Dover Eight escaped the jail and made it to Canada. They were helped along the way by a number of people on the Underground Railroad, except for Thomas Otwell.

William Brinkley was a conductor on the Underground Railroad who helped more than 100 people achieve freedom by traveling through the "notoriously dangerous" town of Camden north to or towards Wilmington, which was also very dangerous for runaway enslaved people. Some of his key rescues include The Tilly Escape of 1856, the Dover Eight in the spring of 1857, and the rescue of 28 people, more than half of which were children, from Dorchester County, Maryland. He had a number of pathways that he would take to various destinations, aided by his brother Nathaniel and Abraham Gibbs, other conductors on the railroad.