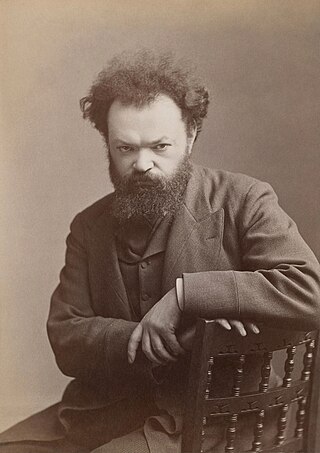

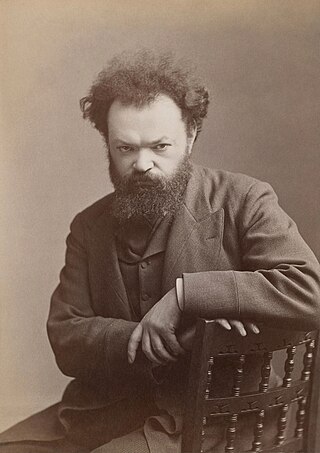

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Anarchism and violence have been linked together by events in anarchist history such as violent revolution, terrorism, and assassination attempts. Leading late 19th century anarchists espoused propaganda by deed, or attentáts, and was associated with a number of incidents of political violence. Anarchist thought, however, is quite diverse on the question of violence. Where some anarchists have opposed coercive means on the basis of coherence, others have supported acts of violent revolution as a path toward anarchy. Anarcho-pacifism is a school of thought within anarchism which rejects all violence.

Anarcho-pacifism, also referred to as anarchist pacifism and pacifist anarchism, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates for the use of peaceful, non-violent forms of resistance in the struggle for social change. Anarcho-pacifism rejects the principle of violence which is seen as a form of power and therefore as contradictory to key anarchist ideals such as the rejection of hierarchy and dominance. Many anarcho-pacifists are also Christian anarchists, who reject war and the use of violence.

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answerable—the authority of God as embodied in the teachings of Jesus. It therefore rejects the idea that human governments have ultimate authority over human societies. Christian anarchists denounce the state, believing it is violent, deceitful and idolatrous.

The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale is an anarchist spy fiction novel by Joseph Conrad, first published in 1907. The story is set in London in 1886 and deals with Mr. Adolf Verloc and his work as a spy for an unnamed country. The Secret Agent is one of Conrad's later political novels in which he moved away from his former tales of seafaring. The novel is dedicated to H. G. Wells and deals broadly with anarchism, espionage, and terrorism. It also deals with exploitation of the vulnerable in Verloc's relationship with his brother-in-law Stevie, who has an intellectual disability. Conrad’s gloomy portrait of London depicted in the novel was influenced by Charles Dickens’ Bleak House.

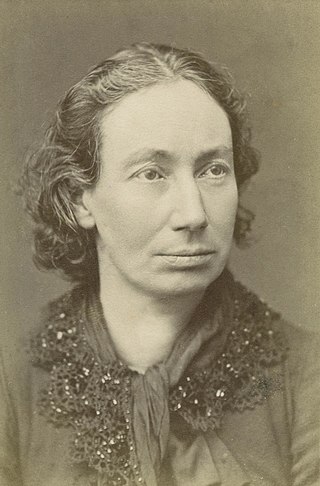

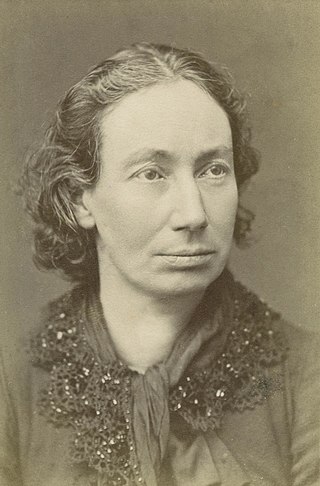

Louise Michel was a teacher and important figure in the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she embraced anarchism. When returning to France she emerged as an important French anarchist and went on speaking tours across Europe. The journalist Brian Doherty has called her the "French grande dame of anarchy." Her use of a black flag at a demonstration in Paris in March 1883 was also the earliest known of what would become known as the anarchy black flag.

Anarchism in the United States began in the mid-19th century and started to grow in influence as it entered the American labor movements, growing an anarcho-communist current as well as gaining notoriety for violent propaganda of the deed and campaigning for diverse social reforms in the early 20th century. By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed and anarcho-communism and other social anarchist currents emerged as the dominant anarchist tendency.

Pyotr Ivanovich Rachkovsky was chief of the Okhrana, the secret police in the Russian Empire. He was based in Paris from 1885 to 1902.

Yuliana Dmitrievna Glinka was a Russian occultist who became associated with theosophy and claims of a Jewish conspiracy.

Émile Pouget was a French journalist, anarchist pamphleteer and trade unionist, known for his pivotal role in the development of revolutionary syndicalism in France. His iconic newspaper, Le Père Peinard, stood out from previous anarchist publications with its inventive use of vernacular and urban slang. Notably, Pouget introduced the term "sabotage" as a tactical approach, a concept later adopted by the General Confederation of Labour (CGT) at its Toulouse Congress in 1897. Pouget's combination of anarchist political theory and revolutionary syndicalist tactics has led several authors to identify him as an early anarcho-syndicalist.

Contemporary anarchism within the history of anarchism is the period of the anarchist movement continuing from the end of World War II and into the present. Since the last third of the 20th century, anarchists have been involved in anti-globalisation, peace, squatter and student protest movements. Anarchists have participated in armed revolutions such as in those that created the Makhnovshchina and Revolutionary Catalonia, and anarchist political organizations such as the International Workers' Association and the Industrial Workers of the World have existed since the 20th century. Within contemporary anarchism, the anti-capitalism of classical anarchism has remained prominent.

Gabriel Kuhn is a political writer and translator based in Sweden.

Sergey Mikhaylovich Stepnyak-Kravchinsky, known in the 19th-century London revolutionary circles as Sergius Stepniak, was a Russian revolutionary. He is mainly known for assassinating General Nikolai Mezentsov, the chief of Russia's Gendarme corps and the head of the country's secret police, with a dagger in the streets of St. Petersburg in 1878.

Duke Constantine Frederick Peter of Oldenburg was the youngest son of Duke Peter Georgievich of Oldenburg and his wife, Princess Therese of Nassau-Weilburg. Known in the court of Emperor Nicholas II as Prince Constantine Petrovich Oldenburgsky, he was the father of the Russian Counts and Countesses von Zarnekau.

Sophia Illarionovna Bardina was a Russian revolutionary.

Charles Wilfred Mowbray was an English anarcho-communist agitator, tailor, trade unionist and public speaker. Mowbray was an active orator and agitator in the Labour Emancipation League, and then the Socialist League, becoming the publisher of the Socialist League's newspaper Commonweal in 1890. At this time he began describing himself as an anarcho-communist. He was arrested in 1892 and charged with conspiracy to murder in a high-profile trial but was acquitted. At this time he reportedly worked as a police informant. From 1894 he lived and worked in the United States where he went on speaker tours before being deported in the wake of the assassination of President McKinley. Back in England he moved away from anarchism and began lecturing on tariff reform (protectionism) and was funded by the National Union of Conservative Associations.

Léon-Jules Léauthier (1874–1894) was a French anarchist who, on 12 November 1893, went to a restaurant in Paris specifically to kill anyone he thought was part of the bourgeoisie. His random victim turned out to be the Serbian ambassador to France, Serge Georgevitch, who survived the attack. Léauthier admitted his guilt and told the authorities that had not known that his victim was an ambassador when he stabbed him. He was sentenced to the Salvation Islands penal colony of Cayenne, French Guiana, where he died within a year during a prisoner revolt.