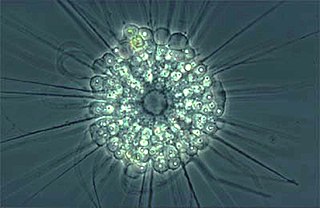

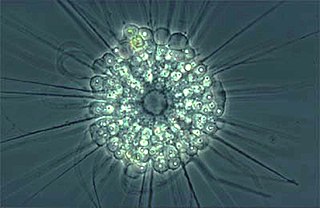

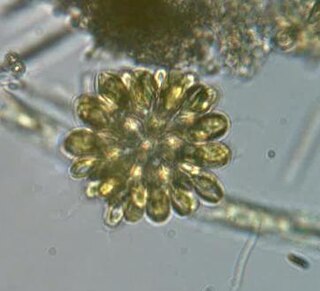

The actinophryids are an order of heliozoa, a polyphyletic array of stramenopiles, having a close relationship with pedinellids and Ciliophrys. They are common in fresh water and occasionally found in marine and soil habitats. Actinophryids are unicellular and roughly spherical in shape, with many axopodia that radiate outward from the cell body. Axopodia are a type of pseudopodia that are supported by hundreds of microtubules arranged in interlocking spirals and forming a needle-like internal structure or axoneme. Small granules, extrusomes, that lie under the membrane of the body and axopodia capture flagellates, ciliates and small metazoa that make contact with the arms.

A flagellate is a cell or organism with one or more whip-like appendages called flagella. The word flagellate also describes a particular construction characteristic of many prokaryotes and eukaryotes and their means of motion. The term presently does not imply any specific relationship or classification of the organisms that possess flagella. However, the term "flagellate" is included in other terms which are more formally characterized.

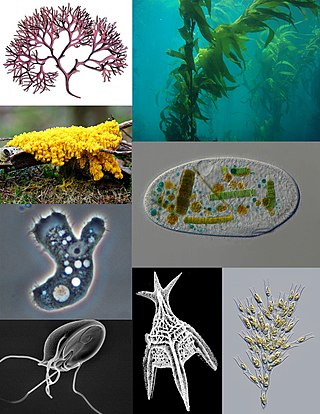

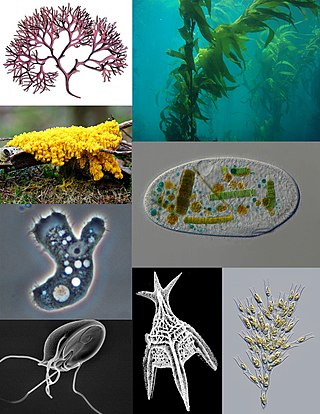

The Stramenopiles, also called Heterokonts, are a clade of organisms distinguished by the presence of stiff tripartite external hairs. In most species, the hairs are attached to flagella, in some they are attached to other areas of the cellular surface, and in some they have been secondarily lost. Stramenopiles represent one of the three major clades in the SAR supergroup, along with Alveolata and Rhizaria.

A flagellum is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are known as flagellates.

The alveolates are a group of protists, considered a major clade and superphylum within Eukarya. They are currently grouped with the stramenopiles and Rhizaria among the protists with tubulocristate mitochondria into the SAR supergroup.

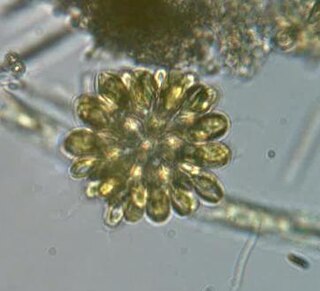

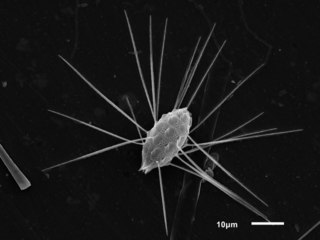

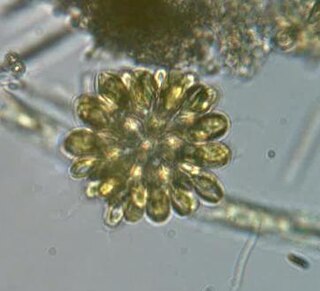

The synurids are a small group of heterokont algae, found mostly in freshwater environments, characterized by cells covered in silica scales.

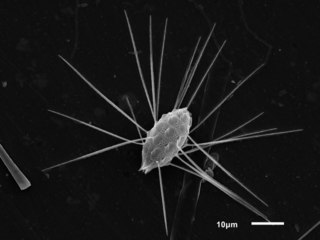

The axodines are a group of unicellular stramenopiles that includes silicoflagellate and rhizochromulinid algae, actinomonad heterotrophic flagellates and actinophryid heliozoa. Alternative classifications treat the dictyochophytes as heterokont algae, or as Chrysophyceae. Other overlapping taxonomic concepts include the Actinochrysophyceae, Actinochrysea or Dictyochophyceae sensu lato. The grouping was proposed on the basis of ultrastructural similarities, and is consistent with subsequent molecular comparisons.

Chromista is a proposed but polyphyletic biological kingdom consisting of single-celled and multicellular eukaryotic species that share similar features in their photosynthetic organelles (plastids). It includes all eukaryotes whose plastids contain chlorophyll c and are surrounded by four membranes. If the ancestor already possessed chloroplasts derived by endosymbiosis from red algae, all non-photosynthetic Chromista have secondarily lost the ability to photosynthesise. Its members might have arisen independently as separate evolutionary groups from the last eukaryotic common ancestor.

The Chrysophyceae, usually called chrysophytes, chrysomonads, golden-brown algae or golden algae are a large group of algae, found mostly in freshwater. Golden algae is also commonly used to refer to a single species, Prymnesium parvum, which causes fish kills.

Stephanopogon is a genus of flagellated marine protist that superficially resembles a ciliate.

In botany, a zoid or zoïd is a reproductive cell that possesses one or more flagella, and is capable of independent movement. Zoid can refer to either an asexually reproductive spore or a sexually reproductive gamete. In sexually reproductive gametes, zoids can be either male or female depending on the species. For example, some brown alga (Phaeophyceae) reproduce by producing multi-flagellated male and female gametes that recombine to form the diploid sporangia. Zoids are primarily found in some protists, diatoms, green alga, brown alga, non-vascular plants, and a few vascular plants. The most common classification group that produces zoids is the heterokonts or stramenopiles. These include green alga, brown alga, oomycetes, and some protists. The term is generally not used to describe motile, flagellated sperm found in animals. Zoid is also commonly confused for zooid which is a single organism that is part of a colonial animal.

David Joseph Patterson is a Northern Irish taxonomist specializing in protozoa and the use of taxonomy in biodiversity informatics.

A protist or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but an artificial grouping of several independent clades that evolved from the last eukaryotic common ancestor.

Trimastix is a genus of excavates, the sole occupant of the order Trimastigida. Trimastix are bacterivorous, free living and anaerobic. When first observed in 1881 by William Kent, the morphology of Trimastix was not well described but over time the oral structure and flagellar organization have become clearer. There are few known species, and the genus's role in the ecosystem is largely unknown. However, it is known that they generally live in marine environments within the tissues of decaying organisms to maintain an anoxic environment. Much interest in this group is related to its close association with other members of Anaeromonadea. These organisms do not have classical mitochondria, and as such, much of the research involving these microbes is aimed at investigating the evolution of mitochondria.

Oxyrrhis marina is a species of heterotrophic dinoflagellate with flagella that is widely distributed in the world's oceans.

The Mastigont system is a series of structures found in several Protists such as thrichomonads and amoebae. It is formed by the basal bodies and several other structures composed of fibrils. Their function is not fully understood. The system is studied and visualised mainly through techniques such as plasma membrane extraction, high-voltage electron microscopy, field emission scanning electron microscopy, the cell-sandwich technique, freeze-etching, and immunocytochemistry.

Mallomonas is a genus comprising unicellular algal eukaryotes and characterized by their intricate cell coverings made of silica scales and bristles. The group was first named and classified by Dr. Maximilian Perty in 1852. These organisms live in freshwater and are widely distributed around the world. Some well known species include Mallomonas caudata and Mallomonas splendens.

Synura is a genus of colonial chrysomonad algae covered in silica scales. It is the most conspicuous genus of the order Synurales.

Protists are the eukaryotes that cannot be classified as plants, fungi or animals. They are mostly unicellular and microscopic. Many unicellular protists, particularly protozoans, are motile and can generate movement using flagella, cilia or pseudopods. Cells which use flagella for movement are usually referred to as flagellates, cells which use cilia are usually referred to as ciliates, and cells which use pseudopods are usually referred to as amoeba or amoeboids. Other protists are not motile, and consequently have no built-in movement mechanism.

Tetrahelia is a genus of four-ciliated protists belonging to the Endohelea, a group of heterotrophic eukaryotes previously considered heliozoa. It is the only genus in the family Tetraheliidae and order Axomonadida. It is a monotypic genus, containing the sole species Tetrahelia pterbica, previously classified as Tetradimorpha.