Tribal sovereignty in the United States is the concept of the inherent authority of indigenous tribes to govern themselves within the borders of the United States. Originally, the U.S. federal government recognized American Indian tribes as independent nations, and came to policy agreements with them via treaties. As the U.S. accelerated its westward expansion, internal political pressure grew for "Indian removal", but the pace of treaty-making grew nevertheless. Then the Civil War forged the U.S. into a more centralized and nationalistic country, fueling a "full bore assault on tribal culture and institutions", and pressure for Native Americans to assimilate. In the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871, without any input from Native Americans, Congress prohibited any future treaties. This move was steadfastly opposed by Native Americans. Currently, the U.S. recognizes tribal nations as "domestic dependent nations" and uses its own legal system to define the relationship between the federal, state, and tribal governments.

Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978), is a United States Supreme Court case deciding that Indian tribal courts have no criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians. The case was decided on March 6, 1978 with a 6–2 majority. The court opinion was written by William Rehnquist, and a dissenting opinion was written by Thurgood Marshall, who was joined by Chief Justice Warren Burger. Justice William J. Brennan did not participate in the decision.

The Menominee are a federally recognized nation of Native Americans, with a 353.894 sq mi (916.581 km2) reservation in Wisconsin. Their historic territory originally included an estimated 10 million acres (40,000 km2) in present-day Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The tribe currently has about 8,700 members.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA), codified at 16 U.S.C. §§ 703–712, is a United States federal law, first enacted in 1916 to implement the convention for the protection of migratory birds between the United States and Great Britain. The statute makes it unlawful without a waiver to pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, or sell nearly 1,100 species of birds listed therein as migratory birds. The statute does not discriminate between live or dead birds and also grants full protection to any bird parts including feathers, eggs, and nests. A March 2020 update of the list increased the number of species to 1,093.

Duro v. Reina, 495 U.S. 676 (1990), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court concluded that Indian tribes could not prosecute Indians who were members of other tribes for crimes committed by those nonmember Indians on their reservations. The decision was not well received by the tribes, because it defanged their criminal codes by depriving them of the power to enforce them against anyone except their own members. In response, Congress amended a section of the Indian Civil Rights Act, 25 U.S.C. § 1301, to include the power to "exercise criminal jurisdiction over all Indians" as one of the powers of self-government.

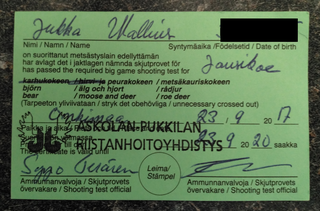

A hunting license is a regulatory or legal mechanism to control hunting.

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903), was a United States Supreme Court case brought against the US government by the Kiowa chief Lone Wolf, who charged that Native American tribes under the Medicine Lodge Treaty had been defrauded of land by Congressional actions in violation of the treaty.

Treaty rights are rights conferred through the signature of a treaty, such as the Svalbard Treaty. Treaty rights are frequently subject to public debate, particularly hunting and fishing rights. Another common source of conflict is management decisions on land or rivers for which Native people have rights.

The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act is a United States federal statute that protects two species of eagle. The bald eagle was chosen as a national emblem of the United States by the Continental Congress of 1782 and was given legal protection by the Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940. This act was expanded to include the golden eagle in 1962. Since the original Act, the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act has been amended several times. It currently prohibits anyone, without a permit issued by the Secretary of the Interior, from "taking" bald eagles. Taking is described to include their parts, nests, or eggs, molesting or disturbing the birds. The Act provides criminal penalties for persons who "take, possess, sell, purchase, barter, offer to sell, purchase or barter, transport, export or import, at any time or any manner, any bald eagle ... [or any golden eagle], alive or dead, or any part, nest, or egg thereof."

Delaware Tribal Business Committee v. Weeks, 430 U.S. 73 (1977), was a case decided by the United States Supreme Court.

Native American civil rights are the civil rights of Native Americans in the United States. Native Americans are citizens of their respective Native nations as well as the United States, and those nations are characterized under the Law of the United States as "domestic dependent nations", a special relationship that creates a particular tension between rights retained via tribal sovereignty and rights that individual Natives obtained as U.S. citizens. This status creates tension today, but was far more extreme before Native people were uniformly granted U.S. citizenship in 1924. Assorted laws and policies of the United States government, some tracing to the pre-Revolutionary colonial period, denied basic human rights—particularly in the areas of cultural expression and travel—to indigenous people.

The National Eagle Repository is operated and managed under the Office of Law Enforcement of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service located at the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge outside of Denver, Colorado. It serves as a central location for the receipt, storage, and distribution of bald and golden eagles that have been found dead. Eagles and eagle parts are available only to Native Americans enrolled in federally recognized tribes for use in religious and cultural ceremonies.

Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49 (1978), was a landmark case in the area of federal Indian law involving issues of great importance to the meaning of tribal sovereignty in the contemporary United States. The Supreme Court sustained a law passed by the governing body of the Santa Clara Pueblo that explicitly discriminated on the basis of sex. In so doing, the Court advanced a theory of tribal sovereignty that weighed the interests of tribes sufficient to justify a law that, had it been passed by a state legislature or Congress, would have almost certainly been struck down as a violation of equal protection. Along with the watershed cases, United States v. Wheeler and Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, Santa Clara completed the trilogy of seminal Indian law cases to come down in the 1978 term.

Menominee Tribe v. United States, 391 U.S. 404 (1968), is a case in which the Supreme Court ruled that the Menominee Indian Tribe kept their historical hunting and fishing rights even after the federal government ceased to recognize the tribe. It was a landmark decision in Native American case law.

South Dakota v. Bourland, 508 U.S. 679 (1993), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that Congress specifically abrogated treaty rights with the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe as to hunting and fishing rights on reservation lands that were acquired for a reservoir.

South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe, Inc., 476 U.S. 498 (1986), is an important U.S. Supreme Court precedent for aboriginal title in the United States decided in the wake of County of Oneida v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York State (1985). Distinguishing Oneida II, the Court held that federal policy did not preclude the application of a state statute of limitations to the land claim of a tribe that had been terminated, such as the Catawba tribe.

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife v. Klamath Indian Tribe, 473 U.S. 753 (1985), was a case appealed to the US Supreme Court by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. The Supreme Court reversed the previous decisions in the District Court and the Court of Appeals stating that the exclusive right to hunt, fish, and gather roots, berries, and seeds on the lands reserved to the Klamath Tribe by the 1864 Treaty was not intended to survive as a special right to be free of state regulation in the ceded lands that were outside the reservation after the 1901 Agreement.

Antoine v. Washington, 420 U.S. 194 (1975), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that treaties and laws must be construed in favor of Native Americans (Indians); that the Supremacy Clause precludes the application of state game laws to the tribe; that Congress showed no intent to subject the tribe to state jurisdiction for hunting; and while the state can regulate non-Indians in the ceded area, Indians must be exempted from such regulations.

Ward v. Race Horse, 163 U.S. 504 (1896), is a United States Supreme Court case argued on March 11–12, 1896, and decided on 25 May 1896.

Herrera v. Wyoming, No. 17-532, 587 U.S. ___ (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that Wyoming's statehood did not void the Crow Tribe's right to hunt on "unoccupied lands of the United States" under an 1868 treaty, and that the Bighorn National Forest did not automatically become "occupied" when the forest was created.