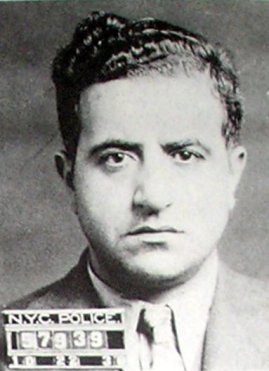

Joseph Michael Valachi was an American mobster in the Genovese crime family who was the first member of the Italian-American Mafia to acknowledge its existence publicly in 1963. He is credited with the popularization of the term cosa nostra.

Vito Genovese was an Italian-born American mafioso and the leader of the Genovese crime family in New York City. A childhood friend and criminal associate of the legendary Lucky Luciano, Genovese took part in the Castellammarese War and helped Luciano shape the Mafia's rise as a major force in organized crime in the United States. He would later lead Luciano's crime family, which was renamed by the FBI after Genovese in 1957.

The Gambino crime family is an Italian-American Mafia crime family and one of the "Five Families" that dominate organized crime activities in New York City, within the nationwide criminal phenomenon known as the American Mafia. The group, which went through five bosses between 1910 and 1957, is named after Carlo Gambino, boss of the family at the time of the McClellan hearings in 1963, when the structure of organized crime first gained public attention. The group's operations extend from New York and the eastern seaboard to California. Its illicit activities include labor and construction racketeering, gambling, loansharking, extortion, money laundering, prostitution, fraud, hijacking, and fencing.

The Havana Conference of 1946 was a historic meeting of United States Mafia and Cosa Nostra leaders in Havana, Cuba. Supposedly arranged by Charles "Lucky" Luciano, the conference was held to discuss important mob policies, rules, and business interests. The Havana Conference was attended by delegations representing crime families throughout the United States. The conference was held during the week of December 22, 1946, at the Hotel Nacional. The Havana Conference is considered to have been the most important mob summit since the Atlantic City Conference of 1929. Decisions made in Havana resonated throughout US crime families during the ensuing decades.

The Genovese crime family, also sometimes referred to as the Westside, is an Italian-American Mafia crime family and one of the "Five Families" that dominate organized crime activities in New York City and New Jersey as part of the American Mafia. The Genovese family has generally maintained a varying degree of influence over many of the smaller mob families outside New York, including ties with the Philadelphia, Cleveland, Patriarca, and Buffalo crime families.

The Apalachin meeting was a historic summit of the American Mafia held at the home of mobster Joseph "Joe the Barber" Barbara, at 625 McFall Road in Apalachin, New York, on November 14, 1957. Allegedly, the meeting was held to discuss various topics including loansharking, narcotics trafficking, and gambling, along with dividing the illegal operations controlled by the recently murdered Albert Anastasia. An estimated 100 Mafiosi from the United States, Italy, and Cuba are thought to have attended this meeting. Immediately after the Anastasia murder that October, and after taking control of the Luciano crime family from Frank Costello, Vito Genovese wanted to legitimize his new power by holding a national Cosa Nostra meeting.

The Five Families refer to five Italian American Mafia crime families that operate in New York City. In 1931, the five families were organized by Salvatore Maranzano following his victory in the Castellammarese War. Maranzano reorganized the Italian American gangs in New York City into the Maranzano, Profaci, Mangano, Luciano, and Gagliano families, which are now known as the Bonanno, Colombo, Gambino, Genovese, and Lucchese families, respectively. Each family had a demarcated territory and an organizationally structured hierarchy and reported to the same overarching governing entity.

Frank Pentangeli is a fictional character from the 1974 film The Godfather Part II, portrayed by Michael V. Gazzo. Gazzo was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his performance, which he lost to Robert De Niro, his co-star from the same film. He is nicknamed "Frankie Five Angels" from his last name, which is formed from the Greek-derived prefix penta- and the Italian word angeli ("angels").

A series of meetings between Sicilian Mafia and American Mafia members were allegedly held at the Grand Hotel et des Palmes in Palermo, Sicily, between October 12–16, 1957. Also called the 1957 Palermo Mafia summit, the gathering allegedly discussed the transatlantic illegal heroin trade between the American and the Sicilian Mafia. The FBI believed it was this meeting that established the Bonanno crime family from New York in the heroin trade.

Anthony C. Strollo, also known as "Tony Bender", was a New York mobster who served as a high-ranking capo and underboss of the Genovese crime family for several decades.

Vincent James Squillante, also known as Jimmy Jerome, was an American New York mobster who belonged to the Gambino crime family and was known as "king of the garbage collection racket". Squillante also worked as an assassin for mob boss Albert "Mad Hatter" Anastasia.

Gaetano Reina was an Italian-American gangster. He was an early American Mafia boss who was the founder of what has for many years been called the Lucchese crime family in New York City. He led the family until his murder on February 26, 1930, on the orders of Joe Masseria.

Michael James Genovese was an alleged boss of the Pittsburgh crime family. References to Michael Genovese as the brother of New York mob boss Vito Genovese are to a different Michael Genovese; Michael James Genovese was first cousin to Vito Genovese.

Nicola Gentile, also known as Nick Gentile, was a Sicilian mafioso and an organized crime figure in New York City during the 1920s and 1930s. He was also known for publishing his memoirs which, violating the mafiosi code known as omerta, revealed many details of the Sicilian and American underworld. Gentile was born in Siculiana, a small village on the south coast of Sicily in the province of Agrigento. He immigrated to the United States arriving in New York at age 18, in 1903. Gentile fled the country in 1937 while out on $15,000 bail after an arrest for heroin trafficking and returned to Sicily to become a boss in the Sicilian Cosa Nostra. In the US, he was known as "Nick" and in Sicily as "Zu Cola".

The American Mafia, commonly referred to in North America as the Italian-American Mafia, the Mafia, or the Mob, is a highly organized Italian-American criminal society and organized crime group. The terms Italian Mafia and Italian Mob apply to these US-based organizations, as well as the separate yet related Sicilian Mafia or other organized crime groups in Italy, or ethnic Italian crime groups in other countries. These organizations are often referred to by its members as Cosa Nostra and by the American government as La Cosa Nostra (LCN). The organization's name is derived from the original Mafia or Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian Mafia, with "American Mafia" originally referring simply to Mafia groups from Sicily operating in the United States.

The Valachi Papers is a 1968 biography written by Peter Maas, telling the story of former mafia member Joe Valachi, a low-ranking member of the New York–based Genovese crime family, who was the first ever government witness coming from the American Mafia itself. His account of his criminal past revealed many previously unknown details of the Mafia. The book was made into a film in 1972, also called The Valachi Papers, starring Charles Bronson as Valachi.

Santo Sorge was a Sicilian Mafioso living in the United States. His exact role has never been very clear; he was one of the great 'unknowns' of the Sicilian and American Mafia. He was one of the highest-level Sicilian Mafia leaders in his time. His counsel was sought in important decisions affecting the American Mafia as well. He traveled extensively between Italy and the United States.

To become member of the Mafia or Cosa Nostra – to become a "man of honor" or a "made man" – an aspiring member must take part in an initiation ritual or initiation ceremony. The ceremony involves significant ritual, oaths, blood, and an agreement is made to follow the rules of the Mafia as presented to the inductee. The first known account of the ceremony dates back to 1877 in Sicily.

The kiss of death is the sign given by a mafioso boss or caporegime that signifies that a member of the crime family has been marked for death, usually as a result of some perceived betrayal. It is unclear how much is based on fact and how much on the imagination of authors, but it remains a cultural meme and appears in literature and films. Illustrative is the scene in the film The Valachi Papers when Vito Genovese gives the kiss of death to Joe Valachi to inform him that his betrayal of "the family" is known, and that he will be executed.

Umberto "Albert" Anastasia was an Italian-American mobster, hitman and crime boss. One of the founders of the modern American Mafia, and a co-founder and later boss of the Murder, Inc. organization, he eventually rose to the position of boss in what became the modern Gambino crime family. He also controlled New York City's waterfront for most of his criminal career, mainly through the dockworker unions. Anastasia was murdered on October 25, 1957, on the orders of Vito Genovese and Carlo Gambino; Gambino subsequently became boss of the family.