Childhood and First Arrest

In 1949, during his first year at university, Gershuni was arrested on charges of creating an underground youth organization and was sentenced to 10 years in the camps. Released in 1954, he worked as a bricklayer.

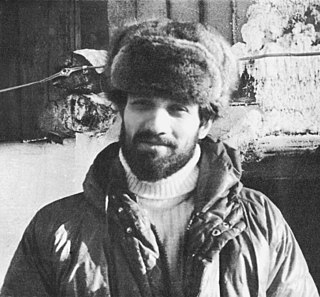

Vladimir Lvovich Gershuni | |

|---|---|

| Владимир Львович Гершуни | |

| Born | 18 March 1930 |

| Died | 17 September 1994 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Citizenship | Soviet Union (1930–1991) → Russia (1991–1994) |

| Occupation(s) | writing poetry, publishing samizdat |

| Known for | human rights activism |

| Movement | dissident movement in the Soviet Union |

Vladimir Lvovich Gershuni (Russian : Влади́мир Льво́вич Гершу́ни, 18 March 1930, Moscow – 17 September 1994, Moscow) was a Soviet dissident and poet. He was a nephew of Grigory Gershuni, a founder of the Socialist Revolutionary Party. He grew up in Soviet children's homes. [1]

In 1949, during his first year at university, Gershuni was arrested on charges of creating an underground youth organization and was sentenced to 10 years in the camps. Released in 1954, he worked as a bricklayer.

In the 1960s, he joined the human rights movement in the Soviet Union, signed a number of collective letters, and participated in collecting materials for Alexander Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago , being himself one of the 255 witnesses consulted by the author. In 1969, he was re-arrested, declared insane and sent for compulsory treatment in the Orel special psychiatric hospital. He was released in 1974.

In 1978, a member of the Royal College of Psychiatrists Dr. Gerard Low-Beer visited Moscow and examined nine Soviet political dissidents, including Gershuni, and came to the conclusion that they have no signs of mental illness, which would require mandatory treatment currently or in the past. [2]

In the 1970s, Gershuni resumed his dissident activities as co-editor of the samizdat magazine Poiski (Quest or Investigations, 1976–1978), and was one of the founders in 1979 of "SMOT", the Free Interprofessional Association of Workers. Simultaneously, he published humorous miniatures in the Soviet press under the pseudonym V. Lvov. In 1982, for the third time, Gershuni was arrested. This time he was charged with publishing a SMOT newsletter and placed in specialized psychiatric hospitals, first Blagoveshchensk in the Soviet Far East, then Talgar in the Almaty Region of Kazakhstan.

Like other political prisoners held in psychiatric hospitals, he was not released until 3 December 1987. [3]

Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky was a Soviet and Russian human rights activist and writer. From the late 1950s to the mid-1970s, he was a prominent figure in the Soviet dissident movement, well known at home and abroad. He spent a total of twelve years in the psychiatric prison-hospitals, labour camps, and prisons of the Soviet Union during Brezhnev rule.

Petro Grigorenko or Petro Hryhorovych Hryhorenko was a high-ranking Soviet Army commander of Ukrainian descent, who in his fifties became a dissident and a writer, one of the founders of the human rights movement in the Soviet Union.

There was systematic political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union, based on the interpretation of political opposition or dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term dissident was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960s until the Fall of Communism. It was used to refer to small groups of marginalized intellectuals whose challenges, from modest to radical to the Soviet regime, met protection and encouragement from correspondents, and typically criminal prosecution or other forms of silencing by the authorities. Following the etymology of the term, a dissident is considered to "sit apart" from the regime. As dissenters began self-identifying as dissidents, the term came to refer to an individual whose non-conformism was perceived to be for the good of a society. The most influential subset of the dissidents is known as the Soviet human rights movement.

The Moscow Helsinki Group was one of Russia's leading human rights organisations. It was originally set up in 1976 to monitor Soviet compliance with the Helsinki Accords and to report to the West on Soviet human rights abuses. It had been forced out of existence in the early 1980s, but was revived in 1989 and continued to operate in Russia.

The Serbsky State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry is a psychiatric hospital and Russia's main center of forensic psychiatry. In the past, the institution was called the Serbsky Institute.

Alexander Pinkhosovich Podrabinek is a Soviet dissident, journalist and commentator. During the Soviet period he was a human rights activist, being exiled, then imprisoned in a corrective-labour colony, for publication of his book Punitive Medicine in Russian and in English.

Andrei Snezhnevsky was a Soviet psychiatrist whose name was lent to the unbridled broadening of the diagnostic borders of schizophrenia in the Soviet Union, the key architect of the Soviet concept of sluggish schizophrenia, the inventor of the term "sluggish schizophrenia", an embodier of history of repressive psychiatry, and a direct participant in psychiatric repression against dissidents.

Leonid Ivanovych Plyushch was a Ukrainian mathematician and Soviet dissident.

Anatoly Ivanovich Koryagin is a psychiatrist and Soviet dissident. He holds a Candidate of Science degree. Along with others, he exposed political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union. He pointed out Russia constructed psychiatric prisons to punish dissidents.

Political abuse of psychiatry, also known as punitive psychiatry, refers to the misuse of psychiatric diagnosis, detention, and treatment to suppress individual or group human rights in society. This abuse involves the deliberate psychiatric diagnosis of individuals who require neither psychiatric restraint nor treatment, often for political purposes.

Global Initiative on Psychiatry (GIP) is an international foundation for mental health reform which took part in the campaign against the political abuse of psychiatry in the USSR. The organization is of NGO type.

Political abuse of psychiatry implies a misuse of psychiatric diagnosis, detention and treatment for the purposes of obstructing the fundamental human rights of certain groups and individuals in a society. In other words, abuse of psychiatry including one for political purposes is the deliberate action of getting citizens certified, who, because of their mental condition, need neither psychiatric restraint nor psychiatric treatment. Psychiatrists have been involved in human rights abuses in states across the world when the definitions of mental disease were expanded to include political disobedience. As scholars have long argued, governmental and medical institutions code menaces to authority as mental diseases during political disturbances. Nowadays, in many countries, political prisoners are sometimes confined and abused in mental institutions. Psychiatric confinement of sane people is uniformly considered a particularly pernicious form of repression.

In the Soviet Union, systematic political abuse of psychiatry took place and was based on the interpretation of political dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

In the Soviet Union, a systematic political abuse of psychiatry took place and was based on the interpretation of political dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

The Lithuanian Helsinki Group was a dissident organization active in the Lithuanian SSR, one of the republics of the Soviet Union, in 1975–83. Established to monitor the implementation of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, better known as Helsinki Accords, it was the first human rights organization in Lithuania. The group published over 30 documents that exposed religious repressions, limitations on freedom of movement, political abuse of psychiatry, discrimination of minorities, persecution of human right activists, and other violations of human rights in the Soviet Union. Most of the documents reached the West and were published by other human rights groups. Members of the group were persecuted by the Soviet authorities. Its activities diminished after it lost members due to deaths, emigration, or imprisonment, though it was never formally disbanded. Some of the group's functions were taken over by the Catholic Committee for the Defense of the Rights of Believers, founded by five priests in 1978. Upon his release from prison, Viktoras Petkus reestablished the Lithuanian Helsinki Group in 1988.

Campaign Against Psychiatric Abuse was a group that was founded by Soviet dissident Viktor Fainberg in April 1975 and participated in the struggle against political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union from 1975 to 1988.

The Working Commission to Investigate the Use of Psychiatry for Political Purposes was an offshoot of the Moscow Helsinki Group and a key source of information on psychiatric repression in the Soviet Union.

The Initiative or Action Group for the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR was the first civic organization of the Soviet human rights movement. Founded in 1969 by 15 dissidents, the unsanctioned group functioned for over six years as a public platform for Soviet dissidents concerned with violations of human rights in the Soviet Union.

In 1965 a human rights movement emerged in the USSR. Those actively involved did not share a single set of beliefs. Many wanted a variety of civil rights — freedom of expression, of religious belief, of national self-determination. To some it was crucial to provide a truthful record of what was happening in the country, not the heavily censored version provided in official media outlets. Others still were "reform Communists" who thought it possible to change the Soviet system for the better.