Andrei Alekseevich Amalrik, alternatively spelled Andrei or Andrey, was a Soviet writer and dissident.

Larisa Iosifovna Bogoraz was a dissident in the Soviet Union.

Andrei Donatovich Sinyavsky was a Russian writer and Soviet dissident known as a defendant in the Sinyavsky–Daniel trial of 1965.

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg, was a Russian journalist, poet, human rights activist and dissident. Between 1961 and 1969 he was sentenced three times to labor camps. In 1979, Ginzburg was released and expelled to the United States, along with four other political prisoners and their families, as part of a prisoner exchange.

A Chronicle of Current Events was one of the longest running samizdat periodicals of the post-Stalinist Soviet Union. This unofficial newsletter reported violations of civil rights and judicial procedure by the Soviet government and responses to those violations by citizens across the Soviet Union. Appearing first in April 1968, it soon became the main voice of the Soviet human rights movement, inside the country and abroad.

Pavel Mikhailovich Litvinov is a Russian-born U.S. physicist, writer, teacher, human rights activist and former Soviet-era dissident.

Lydia Korneyevna Chukovskaya was a Soviet writer, poet, editor, publicist, memoirist and dissident. Her deeply personal writings reflect the human cost of Soviet repression, and she devoted much of her career to defending dissidents such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov. The daughter of the celebrated children's writer Korney Chukovsky, she was wife of scientist Matvei Bronstein, and a close associate and chronicler of the poet Anna Akhmatova.

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term dissident was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960s until the Fall of Communism. It was used to refer to small groups of marginalized intellectuals whose challenges, from modest to radical to the Soviet regime, met protection and encouragement from correspondents, and typically criminal prosecution or other forms of silencing by the authorities. Following the etymology of the term, a dissident is considered to "sit apart" from the regime. As dissenters began self-identifying as dissidents, the term came to refer to an individual whose non-conformism was perceived to be for the good of a society. The most influential subset of the dissidents is known as the Soviet human rights movement.

Dina Isaakovna Kaminskaya was a lawyer and human rights activist in the Soviet Union who was forced to emigrate in 1977 to avoid arrest. She and her husband moved to the United States. She was born to Jewish family in Yekaterinoslav.

The Sinyavsky–Daniel trial was a show trial in the Soviet Union against the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel in February 1966. Sinyavsky and Daniel were convicted of the offense of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda in a Moscow court for publishing their satirical writings of Soviet life abroad under the pseudonyms Abram Tertz and Nikolai Arzhak. The Sinyavsky–Daniel trial was the first Soviet show trial where writers were openly convicted solely for their literary work, provoking appeals from many Soviet intellectuals and other public figures outside the Soviet Union. The Sinyavsky–Daniel led to the Glasnost meeting, the first spontaneous public political demonstration in the Soviet Union after World War II. Sinyavsky and Daniel pled not guilty, unusual for a political charge in the Soviet Union, but were sentenced to seven and five years in labor camps, respectively.

Anatoly Tikhonovich Marchenko was a Soviet dissident, author, and human rights campaigner, who became one of the first two recipients of the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought of the European Parliament when it was awarded to him posthumously in 1988.

Ilya Yankelevich Gabay was a key figure in the civil rights movement in the Soviet Union. Gabay, who was Jewish, was also a literature teacher, poet, and writer. During his lifetime, his works were published only in samizdat.

The Alexander Herzen Foundation was a non-profit foundation, legally established in 1969 in Amsterdam, dedicated to publish samizdat manuscripts from dissidents in the former Soviet Union in the original language or in translation. The Alexander Herzen Foundation was the first to publish accounts of the Sinyavsky-Daniel trial and the works of Andrei Amalrik, Yuli Daniel, Larisa Bogoraz, Andrei Sinyavsky, Pavel Litvinov and others in the West. The Foundation was ended legally in 1998.

The glasnost meeting, also known as the glasnost rally, was the first spontaneous public political demonstration in the Soviet Union after the Second World War. It took place in Moscow on 5 December 1965 as a response to the trial of writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel. The demonstration is considered to mark the beginning of a movement for civil rights in the Soviet Union.

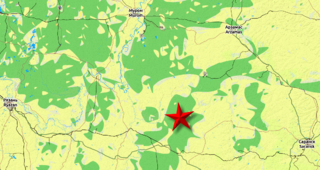

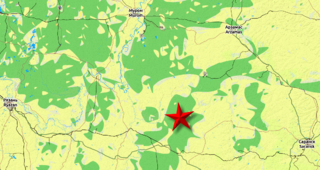

The Dubravny Camp, Special Camp No.3, commonly known as the Dubravlag, was a Gulag labor camp of the Soviet Union located in Yavas, Mordovia from 1948 to 2005.

Alexander Pavlovich Lavut was a mathematician, dissident and a key figure in the civil rights movement in the Soviet Union.

In 1965 a human rights movement emerged in the USSR. Those actively involved did not share a single set of beliefs. Many wanted a variety of civil rights — freedom of expression, of religious belief, of national self-determination. To some it was crucial to provide a truthful record of what was happening in the country, not the heavily censored version provided in official media outlets. Others still were "reform Communists" who thought it possible to change the Soviet system for the better.

Anatoly Aleksandrovich Yakobson was a literary critic, teacher, poet and a central figure in the human rights movement in the Soviet Union.

The Trial of the Four, also Galanskov–Ginzburg trial, was the 1968 trial of Yuri Galanskov, Alexander Ginzburg, Alexey Dobrovolsky and Vera Lahkova for their involvement in samizdat publications. The trial took place in Moscow City Court on January 8–12. All four defendants were sentenced to terms in labour camps. The trial played a major part in consolidating the emerging human rights movement in the Soviet Union.

Alexander P. Babyonyshev is a Soviet and US geologist, historian, demographer, a sociologist. He is a well-known specialist in the study of the loss of the Soviet population.