Larisa Iosifovna Bogoraz was a dissident in the Soviet Union.

There was systematic political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union, based on the interpretation of political opposition or dissent as a psychiatric problem. It was called "psychopathological mechanisms" of dissent.

Yuri Fyodorovich Orlov was a particle accelerator physicist, human rights activist, Soviet dissident, founder of the Moscow Helsinki Group, a founding member of the Soviet Amnesty International group. He was declared a prisoner of conscience while serving nine years in prison and internal exile for monitoring the Helsinki human rights accords, he was declared a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International as a founder of the human rights movement in the Soviet Union. Following his release from exile, Orlov was allowed to emigrate to the U.S. and became a professor of physics at Cornell University.

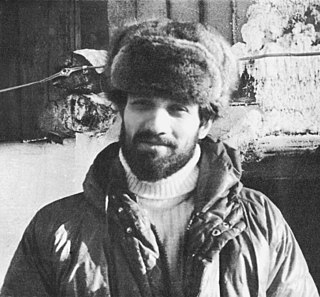

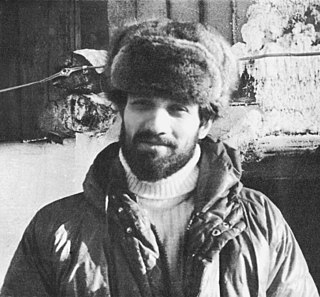

Alexander "Alik" Ilyich Ginzburg, was a Russian journalist, poet, human rights activist and dissident. Between 1961 and 1969 he was sentenced three times to labor camps. In 1979, Ginzburg was released and expelled to the United States, along with four other political prisoners and their families, as part of a prisoner exchange.

A Chronicle of Current Events was one of the longest running samizdat periodicals of the post-Stalinist Soviet Union. This unofficial newsletter reported violations of civil rights and judicial procedure by the Soviet government and responses to those violations by citizens across the Soviet Union. Appearing first in April 1968, it soon became the main voice of the Soviet human rights movement, inside the country and abroad.

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term dissident was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960s until the Fall of Communism. It was used to refer to small groups of marginalized intellectuals whose challenges, from modest to radical to the Soviet regime, met protection and encouragement from correspondents, and typically criminal prosecution or other forms of silencing by the authorities. Following the etymology of the term, a dissident is considered to "sit apart" from the regime. As dissenters began self-identifying as dissidents, the term came to refer to an individual whose non-conformism was perceived to be for the good of a society. The most influential subset of the dissidents is known as the Soviet human rights movement.

The Moscow Helsinki Group was one of Russia's leading human rights organisations. It was originally set up in 1976 to monitor Soviet compliance with the Helsinki Accords and to report to the West on Soviet human rights abuses. It had been forced out of existence in the early 1980s, but was revived in 1989 and continued to operate in Russia.

The Remembrance Day for the Victims of Political Repression is an annual day when victims of political repression in the Soviet Union are remembered and mourned across the Russian Federation.

Alexander Pinkhosovich Podrabinek is a Soviet dissident, journalist and commentator. During the Soviet period he was a human rights activist, being exiled, then imprisoned in a corrective-labour colony, for publication of his book Punitive Medicine in Russian and in English.

Anatoly Tikhonovich Marchenko was a Soviet dissident, author, and human rights campaigner, who became one of the first two recipients of the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought of the European Parliament when it was awarded to him posthumously in 1988.

Sergei Adamovich Kovalyov was a Russian human rights activist and politician. During the Soviet period he was a dissident and, after 1975, a political prisoner.

Andrei Nikolayevich Tverdokhlebov was a Soviet physicist, dissident and human rights activist. In 1970, he founded - along with Valery Chalidze and Andrei Sakharov - the Committee on Human Rights in the USSR. In 1973, Tverdokhlebov - along with Valentin Turchin - founded the first chapter of Amnesty International in the Soviet Union. He also helped found Group 73, a human rights organization that helped political prisoners in the Soviet Union. He was the author/editor of several samizdat publications while in the Soviet Union, which were compiled in the book, "In Defense of Human Rights", published by Khronika Press, New York, in 1975.

Andrey Nikolaevich Derevyankin is a politician, Soviet dissident, and former political prisoner in 1984-1987, 1997–1998, 2000–2004.

Vazif Sirazhutdinovich Meylanov was a Soviet mathematician, social philosopher, writer, Soviet dissident, and political prisoner (1980–1989). He became renowned for his critical works on the theory of socialism, as well as for singular endurance and uncompromising attitude towards authorities during his prison terms.

Tatyana Mikhailovna Velikanova was a mathematician and Soviet dissident. A veteran of the human rights movement in the Soviet Union, she was an editor of A Chronicle of Current Events for most of that underground periodical's existence (1968–1983), bravely exposing her involvement with the anonymously edited and distributed bulletin at a press conference in May 1974.

The Initiative or Action Group for the Defense of Human Rights in the USSR was the first civic organization of the Soviet human rights movement. Founded in 1969 by 15 dissidents, the unsanctioned group functioned for over six years as a public platform for Soviet dissidents concerned with violations of human rights in the Soviet Union.

In 1965 a human rights movement emerged in the USSR. Those actively involved did not share a single set of beliefs. Many wanted a variety of civil rights — freedom of expression, of religious belief, of national self-determination. To some it was crucial to provide a truthful record of what was happening in the country, not the heavily censored version provided in official media outlets. Others still were "reform Communists" who thought it possible to change the Soviet system for the better.

Sergei Ivanovich Grigoryants was a Soviet dissident and political prisoner, journalist, literary critic, chairman of the Glasnost Defense Foundation. He was imprisoned for ten years in Chistopol jail as a political prisoner for anti-Soviet activities, from 1975 to 1980 and then four more years starting in 1983 on similar charges.

Marjorie Milne Farquharson was a political scientist and human rights worker.

Pyotr Ionavich Yakir was a Soviet historian who survived a childhood in the Gulag, and became well known as a critic of Stalinism, though ultimately he denounced dissident activity in the Soviet Union.