Freyr, sometimes anglicized as Frey, is a widely attested god associated with sacral kingship, virility and prosperity, with sunshine and fair weather, and pictured as a phallic fertility god in Norse mythology. Freyr is said to "bestow peace and pleasure on mortals". Freyr, sometimes referred to as Yngvi-Freyr, was especially associated with Sweden and seen as an ancestor of the Swedish royal house.

A solar deity is a sky deity who represents the Sun, or an aspect of it, usually by its perceived power and strength. Solar deities and Sun worship can be found throughout most of recorded history in various forms. The Sun is sometimes referred to by its Latin name Sol or by its Greek name Helios. The English word sun stems from Proto-Germanic *sunnǭ.

Aztec mythology is the body or collection of myths of Aztec civilization of Central Mexico. The Aztecs were Nahuatl-speaking groups living in central Mexico and much of their mythology is similar to that of other Mesoamerican cultures. According to legend, the various groups who were to become the Aztecs arrived from the north into the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco. The location of this valley and lake of destination is clear – it is the heart of modern Mexico City – but little can be known with certainty about the origin of the Aztec. There are different accounts of their origin. In the myth the ancestors of the Mexica/Aztec came from a place in the north called Aztlan, the last of seven nahuatlacas to make the journey southward, hence their name "Azteca." Other accounts cite their origin in Chicomoztoc, "the place of the seven caves," or at Tamoanchan.

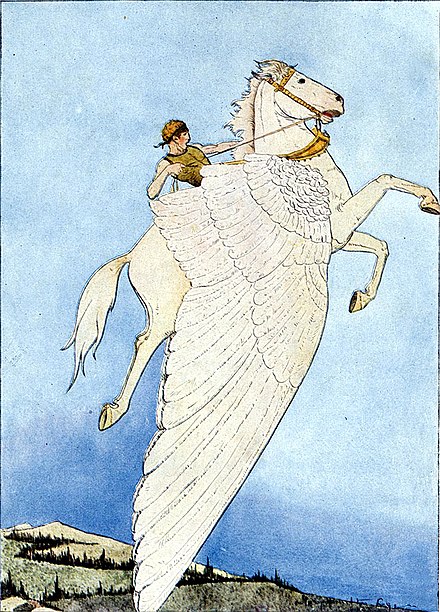

In Norse mythology, Gná is a goddess who runs errands in other worlds for the goddess Frigg and rides the flying, sea-treading horse Hófvarpnir. Gná and Hófvarpnir are attested in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholarly theories have been proposed about Gná as a "goddess of fullness" and as potentially cognate to Fama from Roman mythology. Hófvarpnir and the eight-legged steed Sleipnir have been cited examples of transcendent horses in Norse mythology.

In Norse mythology, Svaðilfari is a stallion that fathered the eight-legged horse Sleipnir with Loki. Svaðilfari was owned by the disguised and unnamed hrimthurs who built the walls of Asgard.

In Norse mythology, Dagr is day personified. This personification appears in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Dagr is stated to be the son of the god Dellingr and is associated with the bright-maned horse Skinfaxi, who "draw[s] day to mankind". Depending on manuscript variation, the Prose Edda adds that Dagr is either Dellingr's son by Nótt, the personified night, or Jörð, the personified Earth. Otherwise, Dagr appears as a common noun simply meaning "day" throughout Old Norse works. Connections have been proposed between Dagr and other similarly named figures in Germanic mythology.

Hermóðr the Brave is a figure in Norse mythology, a son of the god Odin. He is often considered the messenger of the gods.

Phaethon was the son of the Oceanid Clymene and the solar deity Helios in Greek mythology. His name was also used by the Ancient Greeks as an alternative name for the planet Jupiter, the motions and cycles of which were personified in poetry and myth.

Perkūnas was the common Baltic god of thunder, second most important deity in the Baltic pantheon after Dievas. In both Lithuanian and Latvian mythology, he is documented as the god of sky, thunder, lightning, storms, rain, fire, war, law, order, fertility, mountains, and oak trees.

Sól or Sunna is the Sun personified in Norse mythology. One of the two Old High German Merseburg Incantations, written in the 9th or 10th century CE, attests that Sunna is the sister of Sinthgunt. In Norse mythology, Sól is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson.

Guðmundr was a semi-legendary Norse king in Jotunheim, ruling over a land called Glæsisvellir, which was known as the warrior's paradise.

Horse worship is a spiritual practice with archaeological evidence of its existence during the Iron Age and, in some places, as far back as the Bronze Age. The horse was seen as divine, as a sacred animal associated with a particular deity, or as a totem animal impersonating the king or warrior. Horse cults and horse sacrifice were originally a feature of Eurasian nomad cultures. While horse worship has been almost exclusively associated with Indo-European culture, by the Early Middle Ages it was also adopted by Turkic peoples.

The divine twins are a mytheme of Proto-Indo-European religion. The two brothers are youthful horsemen who are either gods or demigods represented as rescuers and healers. Similar mythemes can sometimes be found in non-Indo-European cultures.

Cantabrian mythology refers to the myths, teachings and legends of the Cantabri, a pre-Roman Celtic people of the north coastal region of Iberia (Spain). Over time, Cantabrian mythology was likely diluted by Celtic mythology and Roman mythology with some original meanings lost. Later, the ascendancy of Christendom absorbed or ended the pagan rites of Cantabrian, Celtic and Roman mythology leading to a syncretism. Some relics of Cantabrian mythology remain.

Horse burial is the practice of burying a horse as part of the ritual of human burial, and is found among many Indo-European peoples and others, including Chinese and Turkic peoples. The act indicates the high value placed on horses in the particular cultures and provides evidence of the migration of peoples with a horse culture. Human burials that contain other livestock are rare; in Britain, for example, 31 horse burials have been discovered but only one cow burial, unique in Europe. This process of horse burial is part of a wider tradition of horse sacrifice. An associated ritual is that of chariot burial, in which an entire chariot, with or without a horse, is buried with a dead person.

Horses are an important motif in Chinese mythology. There are many myths about the horse or horses, or horse-like beings, including the pony. Chinese mythology refers to those myths found in the historical geographic area of China. This includes myths in Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other ethnic groups. There are various motifs of horses in Chinese mythology. In some cases the focus is on a horse or horses as the protagonist of the action, in other cases they appear in a supporting role, sometimes as the locomotive power propelling a chariot and its occupant(s). According to a cyclical Chinese calendar system, the time period of 31 January 2014 - 18 February 2015 falls under the category of the (yang) Wood Horse.

The Wǔfāng Shàngdì, or simply Wǔdì or Wǔshén are, in Chinese canonical texts and common Chinese religion, the fivefold manifestation of the supreme God of Heaven. This theology harkens back at least to the Shang dynasty. Described as the "five changeable faces of Heaven", they represent Heaven's cosmic activity which shapes worlds as tán 壇, "altars", imitating its order which is visible in the starry vault, the north celestial pole and its spinning constellations. The Five Deities themselves represent these constellations. In accordance with the Three Powers they have a celestial, a terrestrial and a chthonic form. The Han Chinese identify themselves as the descendants of the Red and Yellow Deities.