Xu Shen | |

|---|---|

| 許慎 | |

| |

| Born | 58 CE Henan, China |

| Died | 148 CE (aged 89 or 90) |

| Occupation(s) | Calligrapher, philologist, politician, writer |

| Notable work | Shuowen Jiezi |

Xu Shen's desire to create an exhaustive reference work resulted in the Shuowen Jiezi (說文解字). The Shuowen has no standard English translation, and is sometimes rendered: "Explain the Graphs and Unravel the Written Words" or "Explaining Graphs and Analyzing Characters." [1] The uniting principle behind each part of the massive project was, as Xu Shen writes in his postface, "to establish defined categories, [to] correct mistaken concepts, for the benefit of scholars and true interpretation of the spirit of language." [5] Intended to be a comprehensive work, it encompasses 15 chapters and over 9,000 small seal script entries, and has a preface and a postface. [5] [2] Xu intentionally listed headwords in pre-Qin characters in order to provide their earliest possible forms, and thereby allow the most faithful interpretation. It is among the first character dictionaries which examined the evolution of characters in detail, and streamlined the "six category" approach to analyzing Chinese writing. [7] It also created a system of 540 semantically organized radicals. [1]

Linguistic theory

In the postface, Xu gives a brief account of the history of writing. According to legend, Chinese characters were first invented by Cangjie, who was inspired by footprints to create a system of signs that refer to the natural world. [7] These original graphs could then be combined to make meaningful characters with referents distinct from their component graphs. [8] This was important for Xu Shen, who emphasized the productivity, even fertility, of Chinese writing. [8] Despite the novel meanings of compound characters, Xu Shen believed that true understanding of composite characters was contingent on an understanding of their components. [2] Providing clear explanation of these relationships lay at the heart of his motivation. [1]

Central to Xu Shen's thought is the contrast between wen (文 patterns) and zi (字 characters), indeed these contrasting categories of graphs receive separate mention in the work's title. Even today, there is disagreement over the exact definitions of the two terms. The Song dynasty scholar Zheng Qiao (鄭樵) first presented the interpretation that wen and zi are the difference between non-compound and compound characters. [7] More recently, other scholars, such as Françoise Bottéro (2002), have argued that the addition of a specifically phonetic element (and thus not simply compounding) marks the principal difference between wen and zi. [8] From this original binary contrast, Xu Shen formally delineated for the first time the six categories (六書) of Chinese characters.

- Indicators of Function (指事), whose forms are iconic without being based on concrete objects. Examples include 上 (shàng) and 下 (xià), indicating up and down respectively. [7]

- Form Imaging or Pictographs (象形), such as 山 (shān), meaning mountain. [7]

- Form and Sound (形聲), which consist of a semantic element and an element indicating pronunciation. [7] The character 汗 (hàn sweat), for example. contains the phonetic marker 干 (gān shield), and the semantic marker 氵(shuĭ water).

- Combining Meaning (會意), which unite two semantic elements. 明, for example contains the sun and the moon, and carries the meaning 'bright'. [7]

- Reciprocally Glossing (轉註), which arose from a divergence of one character into two separate characters still linked in sound and meaning, such as 老 (lăo) and 考 (kǎo). [7]

- Loaning Characters (假借鑑), which essentially indicates one character whose meaning has been broadened to contain multiple definitions. This is seen in bifurcated meanings and pronunciations of 長, which originally meant 'leader' (zhăng), but came to have the second meaning 'long' (cháng). [7]

To organize the thousands of headwords, Xu Shen established 540 radicals, and ordered them from least to greatest complexity. Each radical then headed its own group, which in turn subsumed all composite characters which incorporated the specific radical. The total number of 540 has a cosmological weight, as it can be derived from the product of 6, 9, and 10. 6 and 9 are the numbers of Yin and Yang, and 10 a number signifying completion. This number symbolizes the exhaustive scope of the dictionary.

Within the dictionary itself, each entry first gives the character's meaning, and alternate orthographies. It also accounts for a character's meaning, occasionally pronunciation, and cites examples of its use in the classical texts.

Models and influences

Xu Shen had to rely on a large body of sources to collect the thousands of characters and variants that appear in the Shuowen. Many small script characters were taken from the Cangjiepian (c. 220 BCE); ancient characters were collected from the texts found in Confucius's mansion, and Zhou characters were taken from the Historian Zhou's Primer (c. 578 BCE, the reign of King Xuan). [2]

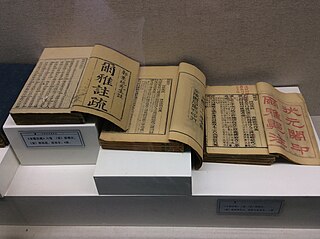

The Shuowen has often been the subject of commentary and study. The earliest reported research was conducted in the Sui dynasty by Yu Yanmo (庾儼默), though this work has not survived. Later in the Tang dynasty (618–907), Li Yangbing (713–741) prepared an edition, though this version is lost as well. [2] The oldest surviving editions go back to a pair of brothers, Xu Xuan (徐鉉) and Xu Kai (徐鍇). The pair lived in the Sui dynasty (581–618), and their work ensured the long-term survival of the Shuowen. [2] The well-known philologist Duan Yucai (段玉裁 1735–1815) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) dedicated his life to studying the Shuowen, and produced the authoritative version and commentary still used today, the Shuowen Jiezi Zhu 說文解字註 (the Annotated Shuowen Jiezi). [2]

Xu Shen's work also provides a valuable resource for linguistic research. Duan Yucai based much of his research on the Shuowen, and the philologist Zhu Junsheng's (朱駿聲) phonological study Explanatory Book of Sounds 說文訓定生 was written as a companion to the Shuowen. [2]

Given the number of dictionaries and philological works that draw heavily from the Shuowen, Xu Shen has towered over the field of Chinese lexicography, and his influence is still felt today. [2]

Criticism

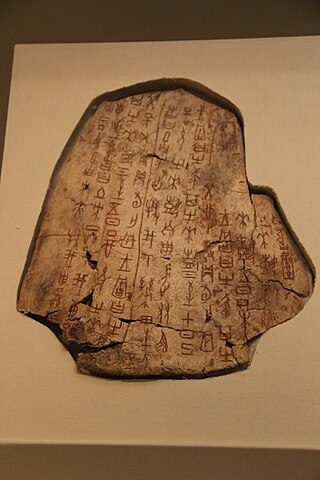

A number of Xu Shen's character analyses are erroneous, as the seal script differs considerably from the older bronzeware script and the even older oracle bone script, both of which were unknown at the time, also to Xu Shen. Karlgren, for example, disputes Xu Shen's interpretation of 巠 (jing) as depicting a subterranean water channel. Referring to the bronze script, he proposes a reading linked to weaving. [9] Furthermore, Xu Shen does not account for historical phonological change between the earliest days of Chinese writing and his own era. This results in inaccurate sound analyses. [10]

See also

Related Research Articles

Written Chinese is a writing system that uses Chinese characters and other symbols to represent the Chinese languages. Chinese characters do not directly represent pronunciation, unlike letters in an alphabet or syllabograms in a syllabary. Rather, the writing system is morphosyllabic: characters are one spoken syllable in length, but generally correspond to morphemes in the language, which may either be independent words, or part of a polysyllabic word. Most characters are constructed from smaller components that may reflect the character's meaning or pronunciation. Literacy requires the memorization of thousands of characters; college-educated Chinese speakers know approximately 4,000. This has led in part to the adoption of complementary transliteration systems as a means of representing the pronunciation of Chinese.

Chinese characters are logographs used to write the Chinese languages and others from regions historically influenced by Chinese culture. Chinese characters have a documented history spanning over three millennia, representing one of the four independent inventions of writing accepted by scholars; of these, they comprise the only writing system continuously used since its invention. Over time, the function, style, and means of writing characters have evolved greatly. Unlike letters in alphabets that reflect the sounds of speech, Chinese characters generally represent morphemes, the units of meaning in a language. Writing a language's entire vocabulary requires thousands of different characters. Characters are created according to several different principles, where aspects of both shape and pronunciation may be used to indicate the character's meaning.

A radical, or indexing component, is a visually prominent component of a Chinese character under which the character is traditionally listed in a Chinese dictionary. The radical for a character is typically a semantic component, but can also be another structural component or even an artificially extracted portion of the character. In some cases the original semantic or phonological connection has become obscure, owing to changes in the meaning or pronunciation of the character over time.

Seal script or sigillary script is a style of writing Chinese characters that was common throughout the latter half of the 1st millennium BC. It evolved organically out of bronze script during the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BC). The variant of seal script used in the state of Qin eventually became comparatively standardized, and was adopted as the formal script across all of China during the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC). It was still widely used for decorative engraving and seals during the Han dynasty.

The Shuowen Jiezi is a Chinese dictionary compiled by Xu Shen c. 100 CE, during the Eastern Han dynasty. While prefigured by earlier Chinese character reference works like the Erya, the Shuowen Jiezi featured the first comprehensive analysis of characters in terms of their structure, and attempted to provide a rationale for their construction. It was also the first to organize its entries into sections according to shared components called radicals.

Oracle bone script is the oldest attested form of written Chinese, dating to the late 2nd millennium BC. Inscriptions were made by carving characters into oracle bones, usually either the shoulder bones of oxen or the plastrons of turtles. The writings themselves mainly record the results of official divinations carried out on behalf of the Late Shang royal family. These divinations took the form of scapulimancy where the oracle bones were exposed to flames, creating patterns of cracks that were then subjected to interpretation. Both the prompt and interpretation were inscribed on the same piece of bone that had been used for the divination itself.

The Erya or Erh-ya is the first surviving Chinese dictionary. The sinologist Bernhard Karlgren concluded that "the major part of its glosses must reasonably date from the 3rd century BC."

Chinese characters are generally logographs, but can be further categorized based on the manner of their creation or derivation. Some characters may be analysed structurally as compounds created from smaller components, while some are not decomposable in this way. A small number of characters originate as pictographs and ideographs, but the vast majority are what are called phono-semantic compounds, which involve an element of pronunciation in their meaning.

The Dongyi or Eastern Yi was a collective term for ancient peoples found in Chinese records. The definition of Dongyi varied across the ages, but in most cases referred to inhabitants of eastern China, then later, the Korean peninsula and Japanese Archipelago. Dongyi refers to different group of people in different periods. As such, the name "Yí" 夷 was something of a catch-all and was applied to different groups over time. According to the earliest Chinese record, the Zuo Zhuan, the Shang dynasty was attacked by King Wu of Zhou while attacking the Dongyi and collapsed afterward.

The term large seal script traditionally refers to written Chinese dating from before the Qin dynasty—now used either narrowly to the writing of the Western and early Eastern Zhou dynasty, or more broadly to also include the oracle bone script. The term deliberately contrasts the small seal script, the official script standardized throughout China during the Qin dynasty, often called merely 'seal script'. Due to the term's lack of precision, scholars often prefer more specific references regarding the provenance of whichever written samples are being discussed.

There are two types of dictionaries regularly used in the Chinese language: 'character dictionaries' list individual Chinese characters, and 'word dictionaries' list words and phrases. Because tens of thousands of characters have been used in written Chinese, Chinese lexicographers have developed a number of methods to order and sort characters to facilitate more convenient reference.

The 1615 Zìhuì is a Chinese dictionary edited by the Ming Dynasty scholar Mei Yingzuo. It is renowned for introducing two lexicographical innovations that continue to be used in the present day: the 214-radical system for indexing Chinese characters, which replaced the classic Shuowen Jiezi dictionary's 540-radical system, and the radical-and-stroke sorting method.

The Shinsen Jikyō is the first Japanese dictionary containing native kun'yomi "Japanese readings" of Chinese characters. The title is also written 新選字鏡 with the graphic variant sen for sen.

Bashe was a python-like Chinese mythological giant snake that ate elephants.

The Shizhoupian is the first known Chinese dictionary, and was written in the ancient Large seal script. The work was traditionally dated to the reign of King Xuan of Zhou (827–782 BCE), but many modern scholars assign it to the state of Qin in the Warring States period. The text is no longer fully extant, and it is now known only through fragments.

Some historical Chinese characters for non-Han peoples were graphically pejorative ethnic slurs, where the racial insult derived not from the Chinese word but from the character used to write it. For instance, written Chinese first transcribed the name Yáo "the Yao people " with the character for yáo猺 "jackal". Most of those terms were replaced in the early 20th-century language reforms; for example, the character for the term yáo was changed, replaced this graphic pejorative meaning "jackal" with another one – a homophone meaning yáo瑤 "precious jade".

The Zilin or Forest of Characters was a Chinese dictionary compiled by the Jin dynasty (266–420) lexicographer Lü Chen (呂忱). It contained 12,824 character head entries, organized by the 540-radical system of the Shuowen Jiezi. In the history of Chinese lexicography, the Zilin followed the Shuowen Jiezi and preceded the Yupian.

The Zitong is a 1254 Chinese dictionary of that was compiled by the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) scholar Li Congzhou 李從周. It discussed orthographic differences between Chinese characters written in different historical styles, including seal script, clerical script, and the contemporary regular script.

The Cangjiepian, also known as the Three Chapters, was a c. 220 BCE Chinese primer and a prototype for Chinese dictionaries. Li Si, Chancellor of the Qin dynasty, compiled it for the purpose of reforming written Chinese into the new orthographic standard Small Seal Script. Beginning in the Han dynasty, many scholars and lexicographers expanded and annotated the Cangjiepian. By the end of the Tang dynasty (618–907), it had become a lost work, but in 1977, archeologists discovered a cache of texts written on bamboo strips, including fragments of the Cangjiepian.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Brown, Kerry, ed. (2014). Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography. Berkshire Publishing. ISBN 9781933782669.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Yong, Heming; Peng, Jing (2008). Chinese Lexicography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199539826.

- ↑ Daijisen entry "Xu Shen" (Kyo Shin in Japanese). Shogakukan.

- ↑ Kanjigen entry "Xu Shen" (Kyo Shin in Japanese). Gakken, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 Xu, Guozhang (1990). "Language and society as seen by Xu Shen, an ancient Chinese lexicographer". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 1990 (81): 51–62. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1990.81.51. S2CID 146757568.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yuan, Xingpei, ed. (2012). The History of Chinese Civilization. Vol. 2. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01306-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lewis, Mark Edwards (1999). Writing and Authority in Early China. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791441148.

- 1 2 3 Bottéro, Françoise (2002). "Revisiting the wén 文 and the zì 字: The Great Chinese Character Hoax". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 74: 14–33.

- ↑ Karlgren, Bernhard (1957). Grammata Serica Recensa. Stockholm: Museum of Far Easter Antiquities. p. 219.

- ↑ Mair, Victor, ed. (2001). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature . New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 46-46. ISBN 0231109849.

Cited works

- Mair, Victor H. (ed.) (2001). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature . New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10984-9. (Amazon Kindle edition.)

Further reading

- He Jiuying 何九盈 (1995). Zhongguo gudai yuyanxue shi (中囯古代语言学史 "A history of ancient Chinese linguistics"). Guangzhou: Guangdong jiaoyu chubanshe.

| Xu Shen | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 許 慎 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 许 慎 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Academics | |

| People | |