The Merina people are the largest ethnic group in Madagascar. They are the "highlander" Malagasy ethnic group of the African island and one of the country's eighteen official ethnic groups. Their origins are mixed, predominantly with Austronesians arriving before the 5th century AD, then many centuries later with mostly Bantu Africans, but also some other ethnic groups. They speak the Merina dialect of the official Malagasy language of Madagascar.

The Betsileo are a highland ethnic group of Madagascar, the third largest in terms of population. They chose their name, meaning "The Many Invincible Ones", after a failed invasion by King Ramitraho of the Menabe kingdom in the early 19th century.

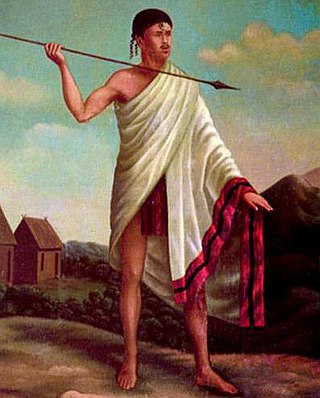

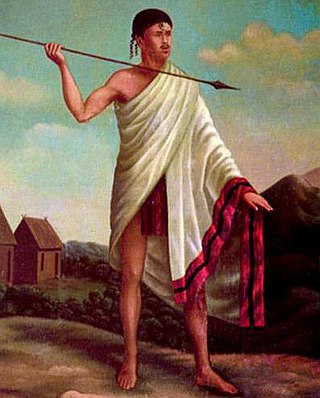

Andrianampoinimerina (1745–1810) ruled the Kingdom of Imerina on Madagascar from 1787 until his death. His reign was marked by the reunification of Imerina following 77 years of civil war, and the subsequent expansion of his kingdom into neighboring territories, thereby initiating the unification of Madagascar under Merina rule. Andrianampoinimerina is a cultural hero and holds near mythic status among the Merina people, and is considered one of the greatest military and political leaders in the history of Madagascar.

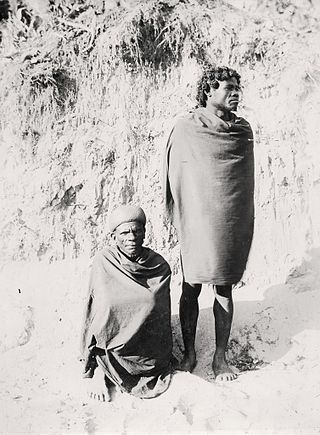

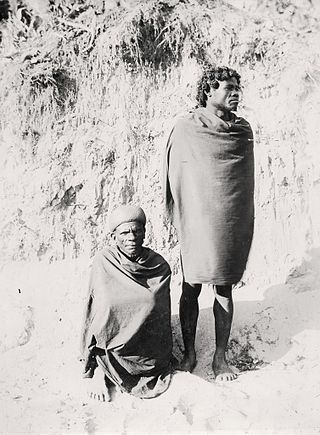

The Malagasy are a group of Austronesian-speaking ethnic groups indigenous to the island country of Madagascar. Traditionally, the population have been divided into ethnic groups. Examples include "Highlander" groups such as the Merina and Betsileo of the central highlands around Antananarivo, Alaotra (Ambatondrazaka) and Fianarantsoa, and the "coastal dwellers" with tribes like the Sakalava, Bara, Vezo, Betsimisaraka, Mahafaly, etc. The Merina are also further divided into two subgroups. The “Merina A” are the Hova and Andriana, and have an average of 30–40% Bantu ancestry. The second subgroup is the “Merina B”, the Andevo, who have an average of 40–50% Bantu ancestry. They make up less than 1/3 of Merina society. The Malagasy population was 2,242,000 in the first census in 1900. Their population experienced a massive growth in the next hundred years, especially under French Madagascar.

The Tsimihety are a Malagasy ethnic group who are found in the north-central region of Madagascar. Their name means "those who never cut their hair", a behavior likely linked to their independence from Sakalava kingdom, located to their west, where cutting hair at the time of mourning was expected. They are found in mountainous part of the island. They are one of the largest Malagasy ethnic groups and their population estimates range between 700,000 and over 1.2 million. This estimation places them as the fourth-largest ethnicity in Madagascar.

The Sakalava are an ethnic group of Madagascar. They are found on the western and northwest region of the island, in a band along the coast. The Sakalava are one of the smallest ethnic groups, constituting about 6.2 percent of the total population, that is about 2,079,000 in 2018. Their name means "people of the long valleys." They occupy the western edge of the island from Toliara in the south to the Sambirano River in the north.

Ambositra is a city in central Madagascar.

Malagasy cuisine encompasses the many diverse culinary traditions of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar. Foods eaten in Madagascar reflect the influence of Southeast Asian, African, Oceanian, Indian, Chinese and European migrants that have settled on the island since it was first populated by seafarers from Borneo between 100 CE and 500 CE. Rice, the cornerstone of the Malagasy diet, was cultivated alongside tubers and other Southeast Asian and Oceanian staples by these earliest settlers. Their diet was supplemented by foraging and hunting wild game, which contributed to the extinction of the island's bird and mammal megafauna. These food sources were later complemented by beef in the form of zebu introduced into Madagascar by East African migrants arriving around 1,000 CE.

The culture of Madagascar reflects the origins of the people Malagasy people in Southeast Asia, East Africa and Oceania. The influence of Arabs, Indians, British, French and Chinese settlers is also evident. The most emblematic instrument of Madagascar, the valiha, is a bamboo tube zither carried to the island by early settlers from southern Borneo, and is very similar in form to those found in Indonesia and the Philippines today. Traditional houses in Madagascar are likewise similar to those of southern Borneo in terms of symbolism and construction, featuring a rectangular layout with a peaked roof and central support pillar. Reflecting a widespread veneration of the ancestors, tombs are culturally significant in many regions and tend to be built of more durable material, typically stone, and display more elaborate decoration than the houses of the living. The production and weaving of silk can be traced back to the island's earliest settlers, and Madagascar's national dress, the woven lamba, has evolved into a varied and refined art. The Southeast Asian cultural influence is also evident in Malagasy cuisine, in which rice is consumed at every meal, typically accompanied by one of a variety of flavorful vegetable or meat dishes. African influence is reflected in the sacred importance of zebu cattle and their embodiment of their owner's wealth, traditions originating on the African mainland. Cattle rustling, originally a rite of passage for young men in the plains areas of Madagascar where the largest herds of cattle are kept, has become a dangerous and sometimes deadly criminal enterprise as herdsmen in the southwest attempt to defend their cattle with traditional spears against increasingly armed professional rustlers.

Andriana was both the noble class and a title of nobility in Madagascar. Historically, many Malagasy ethnic groups lived in highly stratified caste-based social orders in which the andriana were the highest strata. They were above the Hova and Andevo (slaves). The Andriana and the Hova were a part of Fotsy, while the Andevo were Mainty in local terminology.

The Antanosy is a Malagasy ethnic group who primarily live in the Anosy region of southeastern Madagascar, though there are also Antanosy living near Bezaha, where some of the Antanosy moved after the Merina people conquered Anosy. An estimated 360,000 people identify as Antanosy as of 2013.

The Antesaka, also known as Tesaka, or Tesaki, are an ethnic group of Madagascar traditionally concentrated south of Farafangana along the south-eastern coast. They have since spread more widely throughout the island. The Antesaka form about 5% of the population of Madagascar. They have mixed African, Arab and Malayo-Indonesian ancestry, like the western coastal Sakalava people of Madagascar from whom the clan derives. They traditionally have strong marriage taboos and complex funeral rites. The Antesaka typically cultivate coffee, bananas and rice, and those along the coast engage in fishing. A large portion of the population has emigrated to other parts of the island for work, with an estimated 40% of emigrants between 1948 and 1958 permanently settling outside the Antesaka homeland.

The architecture of Madagascar is unique in Africa, bearing strong resemblance to the construction norms and methods of Southern Borneo from which the earliest inhabitants of Madagascar are believed to have immigrated. Throughout Madagascar, the Kalimantan region of Borneo and Oceania, most traditional houses follow a rectangular rather than round form, and feature a steeply sloped, peaked roof supported by a central pillar.

The Antaifasy are an ethnic group of Madagascar inhabiting the southeast coastal region around Farafangana. Historically a fishing and farming people, many Antaifasy were heavily conscripted into forced labor (fanampoana) and brought to Antananarivo as slaves under the 19th century authority of the Kingdom of Imerina. Antaifasy society was historically divided into three groups, each ruled by a king and strongly concentrated around the constraints of traditional moral codes. Approximately 150,000 Antaifasy inhabit Madagascar as of 2013.

The Tandroy are a traditionally nomadic ethnic group of Madagascar inhabiting the arid southern part of the island called Androy, tracing their origins back to the East Africa mainland. In the 17th century however, the Tandroy emerged as a confederation of two groups ruled by the Zafimanara dynasty until flooding caused the kingdom to disband around 1790. The difficult terrain and climate of Tandroy protected and isolated the population, sparing them from subjugation by the Kingdom of Imerina in the 19th century; later, the French colonial authority also struggled to exert its influence over this population. Since independence the Tandroy have suffered prejudice and economic marginalization, prompting widespread migration and intermarriage with other ethnic groups, and leading them to play a key role in protests that sparked the end of President Philibert Tsiranana's administration in 1972.

The Bezanozano are believed to be one of the earliest Malagasy ethnic groups to establish themselves in Madagascar, where they inhabit an inland area between the Betsimisaraka lowlands and the Merina highlands. They are associated with the vazimba, the earliest inhabitants of Madagascar, and the many vazimba tombs throughout Bezanozano territory are sites of pilgrimage, ritual and sacrifice, although the Bezanozano believe the descendants among them of these most ancient of ancestors cannot be identified or known. Their name means "those of many small plaits" in reference to their traditional hairstyle, and like the Merina they practice the famadihana reburial ceremony. There were around 100,000 Bezanozano living in Madagascar in 2013.

The Sihanaka are a Malagasy ethnic group concentrated around Lake Alaotra and the town of Ambatondrazaka in central northeastern Madagascar. Their name means the "people of the swamps" in reference to the marshlands around Lake Alaotra that they inhabit. While rice has long been the principal crop of the region, by the 17th century, the Sihanaka had also become wealthy traders in slaves and other goods, capitalizing on their position on the main trade route between the capital of the neighboring Kingdom of Imerina at Antananarivo and the eastern port of Toamasina. At the turn of the 19th century they came under the control of the Boina Kingdom before submitting to Imerina, which went on to rule over the majority of Madagascar. Today the Sihanaka practice intensive agriculture and rice yields are higher in this region than elsewhere, placing strain on the many unique plant and animal species that depend on the Lake Alaotra ecosystem for survival.

The Tanala are a Malagasy ethnic group that inhabit a forested inland region of south-east Madagascar near Manakara. Their name means "people of the forest." Tanala people identify with one of two sub-groups: the southern Ikongo group, who managed to remain independent in the face of the expanding Kingdom of Imerina in the 19th century, or the northern Menabe group, who submitted to Merina rule. Both groups trace their origin back to a noble ancestor named Ralambo, who is believed to be of Arab descent. They were historically known to be great warriors, having led a successful conquest of the neighboring Antemoro people in the 18th century. They are also reputed to have particular talent in divination through reading seeds or through astrology, which was brought to Madagascar with the Arabs.

The Masikoro are a group of farmers and herders who inhabit areas surrounding the Mikea Forest, a patch of mixed spiny forest and dry deciduous forest along the coast of southwestern Madagascar in Toliara Province. Along with Vezo and Mikea, the Masikoro are Sakalava people, the difference being that Masikoro are of the land, Vezo are of the sea, and Mikea are of the forest.

The Andevo, or slaves, were one of the three principal historical castes among the Merina people of Madagascar, alongside the social strata called the Andriana (nobles) and Hova. The Andevo, along with the other social strata, have also historically existed in other large Malagasy ethnic groups such as the Betsileo people.