Zeus and the Tortoise appears among Aesop's Fables and explains how the tortoise got her shell. It is numbered 106 in the Perry Index. From it derives the proverbial sentiment that 'There's no place like home'.

Zeus and the Tortoise appears among Aesop's Fables and explains how the tortoise got her shell. It is numbered 106 in the Perry Index. From it derives the proverbial sentiment that 'There's no place like home'.

The fable tells how the king of the gods invited all the animals to his wedding but the tortoise never arrived. When asked why, her excuse was that she preferred her own home, so Zeus made her carry her house about forever after.

That excuse in Greek was Οἶκος φίλος, οἶκος ἄριστος, literally 'the home you love is the best'. The fabulist then goes on to comment that 'most people prefer to live simply at home than to live lavishly at someone else's'. [1] The saying became proverbial and was noticed as connected with the fable by Erasmus in his Adagia . [2] The earliest English version of such a proverb, emerging in the 16th century, echoes the comment on the fable: "Home is home, though it's never so homely". [3] The sentiment was eventually used as the second line in the popular song, "Home! Sweet Home!" (1823), which also features the equally proverbial "There's no place like home" in the chorus.

The first recorder of the fable was Cercidas some time in the 3rd century BCE. [4] During the Renaissance it was retold in a mixture of Greek and Latin poetic lines by Barthélemy Aneau in his emblem book Picta Poesis (1552) [5] and by Pantaleon Candidus in his Neo-Latin fable collection of 1604. [6] Later it appeared in idiomatic English in Roger L'Estrange's Fables of Aesop (1692). [7] Earlier, however, an alternative version of the story about the tortoise had been mentioned by the late 4th century CE author Servius in his commentary on Virgil's Aeneid . There it is a mountain nymph called Chelone (Χελώνη, the Greek for tortoise) who did not deign to be present at the wedding of Zeus. The divine messenger Hermes was then sent to throw her and her house into the river, where she was changed into the animal now bearing her name. [8]

In the late 15th century, the Venetian Laurentius Abstemius created a Latin variant on the fable which was subsequently added to their fable collections by both Gabriele Faerno [9] and by L'Estrange. It relates how, when the animals were invited to ask gifts of Zeus at the dawn of time, the snail petitioned for the ability to carry her home with her. Zeus asked if this would not be a troublesome burden, but the snail replied that she preferred this way of avoiding bad neighbours. [10] Another fable attributed to Aesop is being alluded to here, number 100 in the Perry Index. In that story, Momus criticized the divine invention of a house as a gift to mankind because it did not have wheels so as to avoid troublesome neighbours. What was once a divine punishment of the tortoise, Abstemius now reveals as a blessing bestowed.

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of varied and unclear origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

The Miser and his Gold is one of Aesop's Fables that deals directly with human weaknesses, in this case the wrong use of possessions. Since this is a story dealing only with humans, it allows the point to be made directly through the medium of speech rather than be surmised from the situation. It is numbered 225 in the Perry Index.

A wolf in sheep's clothing is an idiom from Jesus's Sermon on the Mount as narrated in the Gospel of Matthew. It warns against individuals who play a duplicitous role. The gospel regards such individuals as dangerous.

The Dog and Its Reflection is one of Aesop's Fables and is numbered 133 in the Perry Index. The Greek language original was retold in Latin and in this way was spread across Europe, teaching the lesson to be contented with what one has and not to relinquish substance for shadow. There also exist Indian variants of the story. The morals at the end of the fable have provided both English and French with proverbs and the story has been applied to a variety of social situations.

Laurentius Abstemius, born Lorenzo Bevilaqua, was an Italian writer and professor of philology, born at Macerata Feltria; his learned name Abstemius, literally "abstemious", plays on his family name of Bevilaqua ("drinkwater"). A Neo-Latin writer of considerable talents at the time of the Humanist revival of letters, his first published works appeared in the 1470s and were distinguished by minute scholarship. During that decade he moved to Urbino and became ducal librarian, although he was to move between there and other parts of Italy thereafter as a teacher.

The Tortoise and the Birds is a fable of probable folk origin, early versions of which are found in both India and Greece. There are also African variants. The moral lessons to be learned from these differ and depend on the context in which they are told.

The Wolf and the Lamb is a well-known fable of Aesop and is numbered 155 in the Perry Index. There are several variant stories of tyrannical injustice in which a victim is falsely accused and killed despite a reasonable defence.

The phrase out of the frying pan into the fire is used to describe the situation of moving or getting from a bad or difficult situation to a worse one, often as the result of trying to escape from the bad or difficult one. It was the subject of a 15th-century fable that eventually entered the Aesopic canon.

The Walnut Tree is one of Aesop's fables and numbered 250 in the Perry Index. It later served as a base for a misogynistic proverb, which encourages the violence against walnut trees, asses and women.

The Fox and the Lion is one of Aesop's Fables and represents a comedy of manners. It is number 10 in the Perry Index.

The Travellers and the Plane Tree is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 175 in the Perry Index. It may be compared with The Walnut Tree as having for theme ingratitude for benefits received. In this story two travellers rest from the sun under a plane tree. One of them describes it as useless and the tree protests at this view when they are manifestly benefiting from its shade.

The Dog and the Wolf is one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 346 in the Perry Index. It has been popular since antiquity as an object lesson of how freedom should not be exchanged for comfort or financial gain. An alternative fable with the same moral concerning different animals is less well known.

The Fox and the Woodman is a cautionary story against hypocrisy included among Aesop's Fables and is numbered 22 in the Perry Index. Although the same basic plot recurs, different versions have included a variety of participants.

The Frog and the Mouse is one of Aesop's Fables and exists in several versions. It is numbered 384 in the Perry Index. There are also Eastern versions of uncertain origin which are classified as Aarne-Thompson type 278, concerning unnatural relationships. The stories make the point that the treacherous are destroyed by their own actions.

The Heron and the Fish is a situational fable constructed to illustrate the moral that one should not be over-fastidious in making choices since, as the ancient proverb proposes, 'He that will not when he may, when he will he shall have nay'. Of ancient but uncertain origin, it gained popularity after appearing among La Fontaine's Fables.

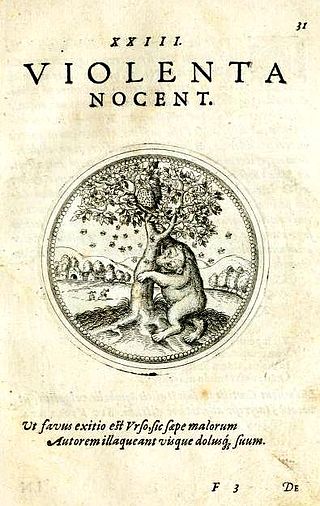

The Bear and the Bees is a fable of North Italian origin that became popular in other countries between the 16th - 19th centuries. There it has often been ascribed to Aesop's fables, although there is no evidence for this and it does not appear in the Perry Index. Various versions have been given different interpretations over time and artistic representations have been common.

There are no less than six fables concerning an impertinent insect, which is taken in general to refer to the kind of interfering person who makes himself out falsely to share in the enterprise of others or to be of greater importance than he is in reality. Some of these stories are included among Aesop's Fables, while others are of later origin, and from them have been derived idioms in several languages.

The classical legend that the swan sings at death was incorporated into one of Aesop's Fables, numbered 399 in the Perry Index. The fable also introduces the proverbial antithesis between the swan and the goose that gave rise to such sayings as ‘Every man thinks his own geese are swans’, in reference to blind partiality, and 'All his swans are turned to geese', referring to a reverse of fortune.

The Oxen and the Creaking Cart is a situational fable ascribed to Aesop and is numbered 45 in the Perry Index. Originally directed against complainers, it was later linked with the proverb 'the worst wheel always creaks most' and aimed emblematically at babblers of all sorts.

In Greek mythology, Chelônê was an oread of Mount Khelydorea in Arkadia.