Nemertea is a phylum of animals also known as ribbon worms or proboscis worms, consisting of 1300 known species. Most ribbon worms are very slim, usually only a few millimeters wide, although a few have relatively short but wide bodies. Many have patterns of yellow, orange, red and green coloration. The foregut, stomach and intestine run a little below the midline of the body, the anus is at the tip of the tail, and the mouth is under the front. A little above the gut is the rhynchocoel, a cavity which mostly runs above the midline and ends a little short of the rear of the body. All species have a proboscis which lies in the rhynchocoel when inactive but everts to emerge just above the mouth to capture the animal's prey with venom. A highly extensible muscle in the back of the rhynchocoel pulls the proboscis in when an attack ends. A few species with stubby bodies filter feed and have suckers at the front and back ends, with which they attach to a host.

The rotifers, commonly called wheel animals or wheel animalcules, make up a phylum of microscopic and near-microscopic pseudocoelomate animals.

Entoprocta, or Kamptozoa, is a phylum of mostly sessile aquatic animals, ranging from 0.1 to 7 millimetres long. Mature individuals are goblet-shaped, on relatively long stalks. They have a "crown" of solid tentacles whose cilia generate water currents that draw food particles towards the mouth, and both the mouth and anus lie inside the "crown". The superficially similar Bryozoa (Ectoprocta) have the anus outside a "crown" of hollow tentacles. Most families of entoprocts are colonial, and all but 2 of the 150 species are marine. A few solitary species can move slowly.

Trematoda is a class of flatworms known as flukes or trematodes. They are obligate internal parasites with a complex life cycle requiring at least two hosts. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is usually a snail. The definitive host, where the flukes sexually reproduce, is a vertebrate. Infection by trematodes can cause disease in all five traditional vertebrate classes: mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish.

Oligochaeta is a subclass of soft-bodied animals in the phylum Annelida, which is made up of many types of aquatic and terrestrial worms, including all of the various earthworms. Specifically, oligochaetes comprise the terrestrial megadrile earthworms, and freshwater or semiterrestrial microdrile forms, including the tubificids, pot worms and ice worms (Enchytraeidae), blackworms (Lumbriculidae) and several interstitial marine worms.

The Turbellaria are one of the traditional sub-divisions of the phylum Platyhelminthes (flatworms), and include all the sub-groups that are not exclusively parasitic. There are about 4,500 species, which range from 1 mm (0.039 in) to large freshwater forms more than 500 mm (20 in) long or terrestrial species like Bipalium kewense which can reach 600 mm (24 in) in length. All the larger forms are flat with ribbon-like or leaf-like shapes, since their lack of respiratory and circulatory systems means that they have to rely on diffusion for internal transport of metabolites. However, many of the smaller forms are round in cross section. Most are predators, and all live in water or in moist terrestrial environments. Most forms reproduce sexually and with few exceptions all are simultaneous hermaphrodites.

Ascidiacea, commonly known as the ascidians or sea squirts, is a paraphyletic class in the subphylum Tunicata of sac-like marine invertebrate filter feeders. Ascidians are characterized by a tough outer "tunic" made of a polysaccharide.

The Aspidogastrea is a small group of flukes comprising about 80 species. It is a subclass of the trematoda, and sister group to the Digenea. Species range in length from approximately one millimeter to several centimeters. They are parasites of freshwater and marine molluscs and vertebrates. Maturation may occur in the mollusc or vertebrate host. None of the species has any economic importance, but the group is of very great interest to biologists because it has several characters which appear to be archaic.

The nephridium is an invertebrate organ, found in pairs and performing a function similar to the vertebrate kidneys. Nephridia remove metabolic wastes from an animal's body. Nephridia come in two basic categories: metanephridia and protonephridia. All nephridia- and kidney- having animals belong to the clade Nephrozoa.

Insect physiology includes the physiology and biochemistry of insect organ systems.

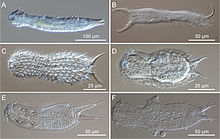

Macrodasyida is an order of gastrotrichs. Members of this order are somewhat worm-like in form, and not more than 1 to 1.5 mm in length.

The Chaetonotida is an order of gastrotrichs. They generally have a tenpin or bottle-like shape.

Leeches are segmented parasitic or predatory worms that comprise the subclass Hirudinea within the phylum Annelida. They are closely related to the oligochaetes, which include the earthworm, and like them have soft, muscular segmented bodies that can lengthen and contract. Both groups are hermaphrodites and have a clitellum, but leeches typically differ from the oligochaetes in having suckers at both ends and in having ring markings that do not correspond with their internal segmentation. The body is muscular and relatively solid, and the coelom, the spacious body cavity found in other annelids, is reduced to small channels.

The reproductive system of gastropods varies greatly from one group to another within this very large and diverse taxonomic class of animals. Their reproductive strategies also vary greatly.

Pseudunela cornuta is a species of minute sea slug, an acochlidian, a shell-less marine and temporarily brackish gastropod mollusk in the family Pseudunelidae. Adults are about 3 mm long and live in the spaces between sand grains.

Chaetonotidae is a family of gastrotrichs in the order Chaetonotida. It is the largest family of gastrotrichs with almost 400 species, some of which are marine and some freshwater. Current classification is largely based on shape and external structures but these are highly variable. Molecular studies show a high level of support for a clade containing Dasydytidae nested within Chaetonotidae.

Diuronotus aspetos is a species of large sized meiofaunal chaetonotid gastrotrich found in the North Atlantic. With Diuronotus rupperti, it is one of the only two species representing the genus Diuronotus.

Macrodasys caudatus is a species of microscopic worm-like metazoan in the family Macrodasyidae in the phylum Gastrotricha. It lives in the interstices between particles of sediment on the seabed in shallow water. It is found in the Indian Ocean, the northeastern Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea and the North Sea.

Lepidodermella squamata is a freshwater species of minute worm in the phylum Gastrotricha.

The annelids, also known as the segmented worms, are a large phylum, with over 22,000 extant species including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to various ecologies – some in marine environments as distinct as tidal zones and hydrothermal vents, others in fresh water, and yet others in moist terrestrial environments.