Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Union. Taken over from the US Air Force by the newly created civilian space agency NASA, it conducted 20 uncrewed developmental flights, and six successful flights by astronauts. The program, which took its name from Roman mythology, cost $2.68 billion. The astronauts were collectively known as the "Mercury Seven", and each spacecraft was given a name ending with a "7" by its pilot.

Splashdown is the method of landing a spacecraft or launch vehicle in a body of water, usually by parachute. This has been the primary recovery method of American capsules including NASA’s Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Orion along with the private SpaceX Dragon. It is also possible for the Boeing Starliner, Russian Soyuz, and the Chinese Shenzhou crewed capsules to land in water in case of contingency. NASA recovered the Space Shuttle solid rocket boosters (SRBs) via splashdown, as is done for Rocket Lab's Electron first stage.

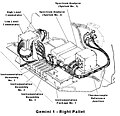

The Agena Target Vehicle, also known as Gemini-Agena Target Vehicle (GATV), was an uncrewed spacecraft used by NASA during its Gemini program to develop and practice orbital space rendezvous and docking techniques, and to perform large orbital changes, in preparation for the Apollo program lunar missions. The spacecraft was based on Lockheed Aircraft's Agena-D upper stage rocket, fitted with a docking target manufactured by McDonnell Aircraft. The name 'Agena' derived from the star Beta Centauri, also known as Agena. The combined spacecraft was a 26-foot (7.92 m)-long cylinder with a diameter of 5 feet (1.52 m), placed into low Earth orbit with the Atlas-Agena launch vehicle. It carried about 14,000 pounds (6,400 kg) of propellant and gas at launch, and had a gross mass at orbital insertion of about 7,200 pounds (3,300 kg).

Cape Canaveral Space Force Station (CCSFS) is an installation of the United States Space Force's Space Launch Delta 45, located on Cape Canaveral in Brevard County, Florida.

Gemini 4 was the second crewed spaceflight in NASA's Project Gemini, occurring in June 1965. It was the tenth crewed American spaceflight. Astronauts James McDivitt and Ed White circled the Earth 66 times in four days, making it the first US flight to approach the five-day flight of the Soviet Vostok 5. The highlight of the mission was the first space walk by an American, during which White floated free outside the spacecraft, tethered to it, for approximately 23 minutes.

Gemini 6A was a 1965 crewed United States spaceflight in NASA's Gemini program. The mission, flown by Wally Schirra and Thomas P. Stafford, achieved the first crewed rendezvous with another spacecraft, its sister Gemini 7. Although the Soviet Union had twice previously launched simultaneous pairs of Vostok spacecraft, these established radio contact with each other, but they had no ability to adjust their orbits in order to rendezvous and came no closer than several kilometers of each other, while the Gemini 6 and 7 spacecraft came as close as one foot (30 cm) and could have docked had they been so equipped.

Gemini 8 was the sixth crewed spaceflight in NASA's Gemini program. It was launched on March 16, 1966, and was the 14th crewed American flight and the 22nd crewed spaceflight overall. The mission conducted the first docking of two spacecraft in orbit, but also suffered the first critical in-space system failure of a U.S. spacecraft which threatened the lives of the astronauts and required an immediate abort of the mission. The crew returned to Earth safely.

Gemini 2 was the second spaceflight of the American human spaceflight program Project Gemini, and was launched and recovered on January 19, 1965. Gemini 2, like Gemini 1, was an uncrewed mission intended as a test flight of the Gemini spacecraft. Unlike Gemini 1, which was placed into orbit, Gemini 2 made a suborbital flight, primarily intended to test the spacecraft's heat shield. It was launched on a Titan II GLV rocket. The spacecraft used for the Gemini 2 mission was later refurbished into the Gemini B configuration, and was subsequently launched on another suborbital flight, along with OPS 0855, as a test for the US Air Force Manned Orbital Laboratory. Gemini spacecraft no. 2 was the first craft to make more than one spaceflight since the X-15, and the only one until Space Shuttle Columbia flew its second mission in 1981; it would also be the only space capsule to be reused until Crew Dragon Endeavour was launched a second time in 2021.

Gemini 11 was the ninth crewed spaceflight mission of NASA's Project Gemini, which flew from September 12 to 15, 1966. It was the 17th crewed American flight and the 25th spaceflight to that time. Astronauts Pete Conrad and Dick Gordon performed the first direct-ascent rendezvous with an Agena Target Vehicle, docking with it 1 hour 34 minutes after launch; used the Agena rocket engine to achieve a record high-apogee Earth orbit; and created a small amount of artificial gravity by spinning the two spacecraft connected by a tether. Gordon also performed two extra-vehicular activities for a total of 2 hours 41 minutes.

Gemini 12 was a 1966 crewed spaceflight in NASA's Project Gemini. It was the 10th and final crewed Gemini flight, the 18th crewed American spaceflight, and the 26th spaceflight of all time, including X-15 flights over 100 kilometers (54 nmi). Commanded by Gemini VII veteran James A. Lovell, the flight featured three periods of extravehicular activity (EVA) by rookie Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin, lasting a total of 5 hours and 30 minutes. It also achieved the fifth rendezvous and fourth docking with an Agena target vehicle.

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) was part of the United States Air Force (USAF) human spaceflight program in the 1960s. The project was developed from early USAF concepts of crewed space stations as reconnaissance satellites, and was a successor to the canceled Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar military reconnaissance space plane. Plans for the MOL evolved into a single-use laboratory, for which crews would be launched on 30-day missions, and return to Earth using a Gemini B spacecraft derived from NASA's Gemini spacecraft and launched with the laboratory.

Mercury-Atlas 10 (MA-10) was a cancelled early crewed space mission, which would have been the last flight in NASA's Mercury program. It was planned as a three-day extended mission, to launch in late 1963; the spacecraft, Freedom 7-II, would have been flown by Alan Shepard, a veteran of the suborbital Mercury-Redstone 3 mission in 1961. However, it was cancelled after the success of the one-day Mercury-Atlas 9 mission in May 1963, to allow NASA to focus its efforts on the more advanced two-man Gemini program.

Project Gemini was the second United States human spaceflight program to fly. Conducted after the first American crewed space program, Project Mercury, while the Apollo program was still in early development, Gemini was conceived in 1961 and concluded in 1966. The Gemini spacecraft carried a two-astronaut crew. Ten Gemini crews and 16 individual astronauts flew low Earth orbit (LEO) missions during 1965 and 1966.

A space capsule is a spacecraft designed to transport cargo, scientific experiments, and/or astronauts to and from space. Capsules are distinguished from other spacecraft by the ability to survive reentry and return a payload to the Earth's surface from orbit or sub-orbit, and are distinguished from other types of recoverable spacecraft by their blunt shape, not having wings and often containing little fuel other than what is necessary for a safe return. Capsule-based crewed spacecraft such as Soyuz or Orion are often supported by a service or adapter module, and sometimes augmented with an extra module for extended space operations. Capsules make up the majority of crewed spacecraft designs, although one crewed spaceplane, the Space Shuttle, has flown in orbit.

A boilerplate spacecraft, also known as a mass simulator, is a nonfunctional craft or payload that is used to test various configurations and basic size, load, and handling characteristics of rocket launch vehicles. It is far less expensive to build multiple, full-scale, non-functional boilerplate spacecraft than it is to develop the full system. In this way, boilerplate spacecraft allow components and aspects of cutting-edge aerospace projects to be tested while detailed contracts for the final project are being negotiated. These tests may be used to develop procedures for mating a spacecraft to its launch vehicle, emergency access and egress, maintenance support activities, and various transportation processes.

The Atlas-Agena was an American expendable launch system derived from the SM-65 Atlas missile. It was a member of the Atlas family of rockets, and was launched 109 times between 1960 and 1978. It was used to launch the first five Mariner uncrewed probes to the planets Venus and Mars, and the Ranger and Lunar Orbiter uncrewed probes to the Moon. The upper stage was also used as an uncrewed orbital target vehicle for the Gemini crewed spacecraft to practice rendezvous and docking. However, the launch vehicle family was originally developed for the Air Force and most of its launches were classified DoD payloads.

NASA's Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Mission Control Center, also known by its radio callsign, Houston, is the facility at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, that manages flight control for the United States human space program, currently involving astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS). The center is in Building 30 at the Johnson Space Center and is named after Christopher C. Kraft Jr., a NASA engineer and manager who was instrumental in establishing the agency's Mission Control operation, and was the first Flight Director.

The Titan II GLV or Gemini-Titan II was an American expendable launch system derived from the Titan II missile, which was used to launch twelve Gemini missions for NASA between 1964 and 1966. Two uncrewed launches followed by ten crewed ones were conducted from Launch Complex 19 at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, starting with Gemini 1 on April 8, 1964.

Advanced Gemini was a series of proposals that would have extended the Gemini program by the addition of various missions, including crewed low Earth orbit, circumlunar and lunar landing missions. Gemini was the second crewed spaceflight program operated by NASA, and consisted of a two-seat spacecraft capable of maneuvering in orbit, docking with uncrewed spacecraft such as Agena Target Vehicles, and allowing the crew to perform tethered extra-vehicular activities.

The 6555th Aerospace Test Group is an inactive United States Air Force unit. It was last assigned to the Eastern Space and Missile Center and stationed at Patrick Air Force Base, Florida. It was inactivated on 1 October 1990.