Structural geology is the study of the three-dimensional distribution of rock units with respect to their deformational histories. The primary goal of structural geology is to use measurements of present-day rock geometries to uncover information about the history of deformation (strain) in the rocks, and ultimately, to understand the stress field that resulted in the observed strain and geometries. This understanding of the dynamics of the stress field can be linked to important events in the geologic past; a common goal is to understand the structural evolution of a particular area with respect to regionally widespread patterns of rock deformation due to plate tectonics.

In continuum mechanics, stress is a physical quantity that expresses the internal forces that neighbouring particles of a continuous material exert on each other, while strain is the measure of the deformation of the material. For example, when a solid vertical bar is supporting an overhead weight, each particle in the bar pushes on the particles immediately below it. When a liquid is in a closed container under pressure, each particle gets pushed against by all the surrounding particles. The container walls and the pressure-inducing surface push against them in (Newtonian) reaction. These macroscopic forces are actually the net result of a very large number of intermolecular forces and collisions between the particles in those molecules. Stress is frequently represented by a lowercase Greek letter sigma (σ).

In physics and materials science, elasticity is the ability of a body to resist a distorting influence and to return to its original size and shape when that influence or force is removed. Solid objects will deform when adequate loads are applied to them; if the material is elastic, the object will return to its initial shape and size after removal. This is in contrast to plasticity, in which the object fails to do so and instead remains in its deformed state.

In structural geology, a fold is a stack of originally planar surfaces, such as sedimentary strata, that are bent or curved during permanent deformation. Folds in rocks vary in size from microscopic crinkles to mountain-sized folds. They occur as single isolated folds or in periodic sets. Synsedimentary folds are those formed during sedimentary deposition.

A shear zone is a very important structural discontinuity surface in the Earth's crust and upper mantle. It forms as a response to inhomogeneous deformation partitioning strain into planar or curviplanar high-strain zones. Intervening (crustal) blocks stay relatively unaffected by the deformation. Due to the shearing motion of the surrounding more rigid medium, a rotational, non co-axial component can be induced in the shear zone. Because the discontinuity surface usually passes through a wide depth-range, a great variety of different rock types with their characteristic structures are produced.

A strainmeter is an instrument used by geophysicists to measure the deformation of the Earth. Linear strainmeters measure the changes in the distance between two points, using either a solid piece of material or a laser interferometer . The type using a solid length standard was invented by Benioff in 1932, using an iron pipe; later instruments used rods made of fused quartz. Modern instruments of this type can make measurements of length changes over very small distances, and are commonly placed in boreholes to measure small changes in the diameter of the borehole. Another type of borehole instrument detects changes in a volume filled with fluid . The most common type is the dilatometer invented by Sacks and Evertson in the USA (patent 3,635,076); a design that uses specially shaped volumes to measure the strain tensor has been developed by Sakata in Japan.

In geology, aseismic creep or fault creep is measurable surface displacement along a fault in the absence of notable earthquakes. Aseismic creep may also occur as "after-slip" days to years after an earthquake. Notable examples of aseismic slip include faults in California.

In geology, a vein is a distinct sheetlike body of crystallized minerals within a rock. Veins form when mineral constituents carried by an aqueous solution within the rock mass are deposited through precipitation. The hydraulic flow involved is usually due to hydrothermal circulation.

Geodynamics is a subfield of geophysics dealing with dynamics of the Earth. It applies physics, chemistry and mathematics to the understanding of how mantle convection leads to plate tectonics and geologic phenomena such as seafloor spreading, mountain building, volcanoes, earthquakes, faulting and so on. It also attempts to probe the internal activity by measuring magnetic fields, gravity, and seismic waves, as well as the mineralogy of rocks and their isotopic composition. Methods of geodynamics are also applied to exploration of other planets.

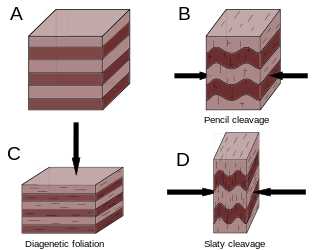

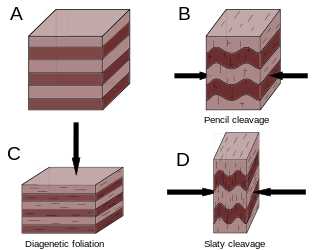

Cleavage, in structural geology and petrology, describes a type of planar rock feature that develops as a result of deformation and metamorphism. The degree of deformation and metamorphism along with rock type determines the kind of cleavage feature that develops. Generally these structures are formed in fine grained rocks composed of minerals affected by pressure solution.

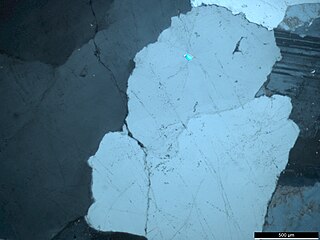

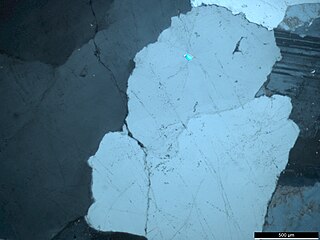

A deformation mechanism, in geotechnical engineering, is a process occurring at a microscopic scale that is responsible for changes in a material's internal structure, shape and volume. The process involves planar discontinuity and/or displacement of atoms from their original position within a crystal lattice structure. These small changes are preserved in various microstructures of materials such as rocks, metals and plastics, and can be studied in depth using optical or digital microscopy.

Material failure theory is an interdisciplinary field of materials science and solid mechanics which attempts to predict the conditions under which solid materials fail under the action of external loads. The failure of a material is usually classified into brittle failure (fracture) or ductile failure (yield). Depending on the conditions most materials can fail in a brittle or ductile manner or both. However, for most practical situations, a material may be classified as either brittle or ductile.

Mary Lou Zoback is an American geophysicist who led the world stress map project of the International Lithosphere Program. Zoback is currently a member of the U.S. Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board.

The Ceraunius Fossae are a set of fractures in the northern Tharsis region of Mars. They lie directly south of the large volcano Alba Mons and consist of numerous parallel faults and tension cracks that deform the ancient highland crust. In places, younger lava flows cover the fractured terrain, dividing it into several large patches or islands. They are found in the Tharsis quadrangle.

In Earth science, as opposed to Materials Science, Ductility refers to the capacity of a rock to deform to large strains without macroscopic fracturing. Such behavior may occur in unlithified or poorly lithified sediments, in weak materials such as halite or at greater depths in all rock types where higher temperatures promote crystal plasticity and higher confining pressures suppress brittle fracture. In addition, when a material is behaving ductilely, it exhibits a linear stress vs strain relationship past the elastic limit.

Thick-skinned deformation is a geological term which refers to crustal shortening that involves basement rocks and deep-seated faults as opposed to only the upper units of cover rocks above the basement which is known as thin-skinned deformation. While thin-skinned deformation is common in many different localities, thick-skinned deformation requires much more strain to occur and is a rarer type of deformation.

Strain partitioning is commonly referred to as a deformation process in which the total strain experienced on a rock, area, or region, is heterogeneously distributed in terms of the strain intensity and strain type. This process is observed on a range of scales spanning from the grain – crystal scale to the plate – lithospheric scale, and occurs in both the brittle and plastic deformation regimes. The manner and intensity by which strain is distributed are controlled by a number of factors listed below.

David D. Pollard is a professor in geomechanics and structural geology at Stanford University.

Paleostress inversion refers to the determination of paleostress history from evidence found in rocks, based on the principle that past tectonic stress should have left traces in the rocks. Such relationships have been discovered from field studies for years: qualitative and quantitative analyses of deformation structures are useful for understanding the distribution and transformation of paleostress fields controlled by sequential tectonic events. Deformation ranges from microscopic to regional scale, and from brittle to ductile behaviour, depending on the rheology of the rock, orientation and magnitude of the stress etc. Therefore, detailed observations in outcrops, as well as in thin sections, are important in reconstructing the paleostress trajectories.

Microcracks in rock, also known as microfractures and cracks, are spaces in rock with the longest length of 1000 μm and the other two dimensions of 10 μm. In general, the ratio of width to length of microcracks is between 10−3 to 10−5.