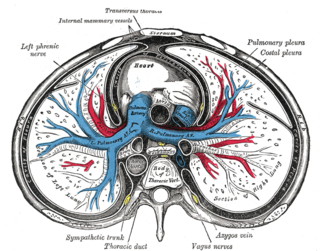

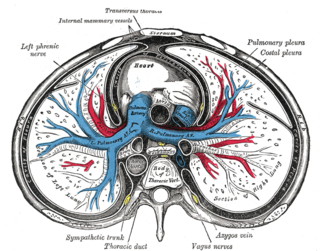

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong inelastic connective tissue, and an inner layer made of serous membrane. It encloses the pericardial cavity, which contains pericardial fluid, and defines the middle mediastinum. It separates the heart from interference of other structures, protects it against infection and blunt trauma, and lubricates the heart's movements.

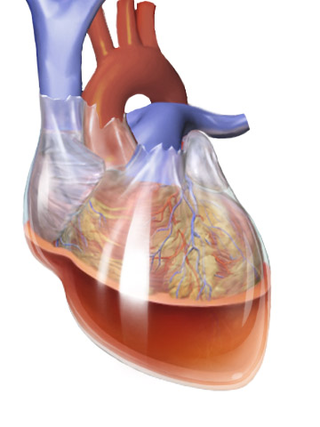

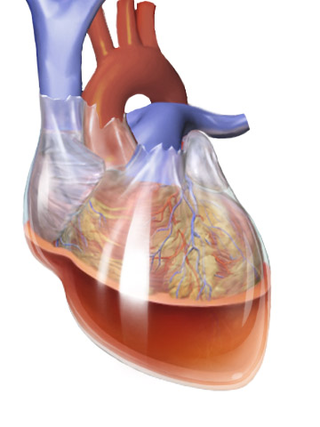

Cardiac tamponade, also known as pericardial tamponade, is a compression of the heart due to pericardial effusion. Onset may be rapid or gradual. Symptoms typically include those of obstructive shock including shortness of breath, weakness, lightheadedness, and cough. Other symptoms may relate to the underlying cause.

Pericarditis is inflammation of the pericardium, the fibrous sac surrounding the heart. Symptoms typically include sudden onset of sharp chest pain, which may also be felt in the shoulders, neck, or back. The pain is typically less severe when sitting up and more severe when lying down or breathing deeply. Other symptoms of pericarditis can include fever, weakness, palpitations, and shortness of breath. The onset of symptoms can occasionally be gradual rather than sudden.

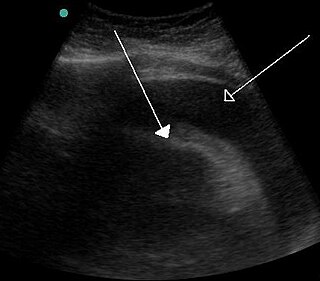

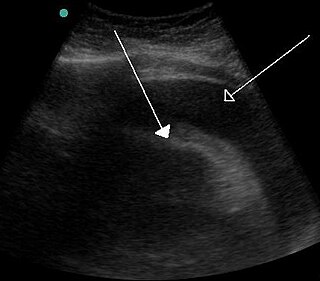

Pericardiocentesis (PCC), also called pericardial tap, is a medical procedure where fluid is aspirated from the pericardium.

Dressler syndrome is a secondary form of pericarditis that occurs in the setting of injury to the heart or the pericardium. It consists of fever, pleuritic pain, pericarditis and/or pericardial effusion.

A pericardial effusion is an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the pericardial cavity. The pericardium is a two-part membrane surrounding the heart: the outer fibrous connective membrane and an inner two-layered serous membrane. The two layers of the serous membrane enclose the pericardial cavity between them. This pericardial space contains a small amount of pericardial fluid, normally 15-50 mL in volume. The pericardium, specifically the pericardial fluid provides lubrication, maintains the anatomic position of the heart in the chest, and also serves as a barrier to protect the heart from infection and inflammation in adjacent tissues and organs.

Pericardial fluid is the serous fluid secreted by the serous layer of the pericardium into the pericardial cavity. The pericardium consists of two layers, an outer fibrous layer and the inner serous layer. This serous layer has two membranes which enclose the pericardial cavity into which is secreted the pericardial fluid. The fluid is similar to the cerebrospinal fluid of the brain which also serves to cushion and allow some movement of the organ.

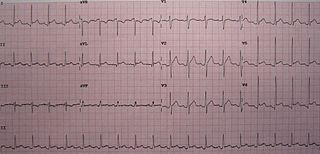

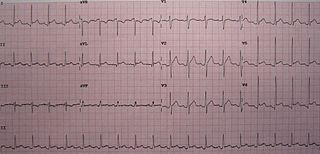

Electrical alternans is an electrocardiographic phenomenon of alternation of QRS complex amplitude or axis between beats and a possible wandering base-line. It is seen in cardiac tamponade and severe pericardial effusion and is thought to be related to changes in the ventricular electrical axis due to fluid in the pericardium, as the heart essentially wobbles in the fluid filled pericardial sac.

Pericardiectomy is the surgical removal of part or most of the pericardium. This operation is most commonly used to relieve constrictive pericarditis, or to remove a pericardium that is calcified and fibrous. It may also be used for severe or recurrent cases of pericardial effusion. Post-operative outcomes and mortality are significantly impacted by the disease it is used to treat.

Myocardial rupture is a laceration of the ventricles or atria of the heart, of the interatrial or interventricular septum, or of the papillary muscles. It is most commonly seen as a serious sequela of an acute myocardial infarction.

Autoimmune heart diseases are the effects of the body's own immune defense system mistaking cardiac antigens as foreign and attacking them leading to inflammation of the heart as a whole, or in parts. The commonest form of autoimmune heart disease is rheumatic heart disease or rheumatic fever.

Obstructive shock is one of the four types of shock, caused by a physical obstruction in the flow of blood. Obstruction can occur at the level of the great vessels or the heart itself. Causes include pulmonary embolism, cardiac tamponade, and tension pneumothorax. These are all life-threatening. Symptoms may include shortness of breath, weakness, or altered mental status. Low blood pressure and tachycardia are often seen in shock. Other symptoms depend on the underlying cause.

Hemopericardium refers to blood in the pericardial sac of the heart. It is clinically similar to a pericardial effusion, and, depending on the volume and rapidity with which it develops, may cause cardiac tamponade.

Tuberculous pericarditis is a form of pericarditis. It is a condition in which the pericardium surrounding the heart is infected by the bacterial species Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculous pericarditis accounts for a significant percentage of presentations of tuberculosis worldwide. The condition has four stages of disease which manifests with clinical presentations ranging from acute pericarditis to overt heart failure. Tuberculous pericarditis is an under-diagnosed condition. Diagnosis often requires a range of diagnostic tools, including pericardiocentesis, biochemical tests, and imaging. Treatment of this disease is similar to treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Alternative treatment options to reduce cardiac complications are also available.

Uremic pericarditis is a form of pericarditis. It causes fibrinous pericarditis. The main cause of the disease is poorly understood.

Myocardial infarction complications may occur immediately following a heart attack, or may need time to develop. After an infarction, an obvious complication is a second infarction, which may occur in the domain of another atherosclerotic coronary artery, or in the same zone if there are any live cells left in the infarct.

Postpericardiotomy syndrome (PPS) is a medical syndrome referring to an immune phenomenon that occurs days to months after surgical incision of the pericardium. PPS can also be caused after a trauma, a puncture of the cardiac or pleural structures, after percutaneous coronary intervention, or due to pacemaker or pacemaker wire placement.

Chest pain in children is the pain felt in the chest by infants, children and adolescents. In most cases the pain is not associated with the heart. It is primarily identified by the observance or report of pain by the infant, child or adolescent by reports of distress by parents or caregivers. Chest pain is not uncommon in children. Many children are seen in ambulatory clinics, emergency departments and hospitals and cardiology clinics. Most often there is a benign cause for the pain for most children. Some have conditions that are serious and possibly life-threatening. Chest pain in pediatric patients requires careful physical examination and a detailed history that would indicate the possibility of a serious cause. Studies of pediatric chest pain are sparse. It has been difficult to create evidence-based guidelines for evaluation.

Purulent pericarditis refers to localized inflammation in the setting of infection of the pericardial sac surrounding the heart. In contrast to other causes of pericarditis which may have a viral etiology, purulent pericarditis refers specifically to bacterial or fungal infection of the pericardial sac. Clinical etiologies of purulent pericarditis may include recent surgery, adjacent infection, trauma, or even primary infection. The onset of purulent pericarditis is usually acute, with most individuals presenting to a medical facility approximately 3 days following the onset of symptoms.