Fructose, or fruit sugar, is a ketonic simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galactose, that are absorbed by the gut directly into the blood of the portal vein during digestion. The liver then converts both fructose and galactose into glucose, so that dissolved glucose, known as blood sugar, is the only monosaccharide present in circulating blood.

Sorbitol, less commonly known as glucitol, is a sugar alcohol with a sweet taste which the human body metabolizes slowly. It can be obtained by reduction of glucose, which changes the converted aldehyde group (−CHO) to a primary alcohol group (−CH2OH). Most sorbitol is made from potato starch, but it is also found in nature, for example in apples, pears, peaches, and prunes. It is converted to fructose by sorbitol-6-phosphate 2-dehydrogenase. Sorbitol is an isomer of mannitol, another sugar alcohol; the two differ only in the orientation of the hydroxyl group on carbon 2. While similar, the two sugar alcohols have very different sources in nature, melting points, and uses.

Dietary fiber or roughage is the portion of plant-derived food that cannot be completely broken down by human digestive enzymes. Dietary fibers are diverse in chemical composition, and can be grouped generally by their solubility, viscosity, and fermentability, which affect how fibers are processed in the body. Dietary fiber has two main components: soluble fiber and insoluble fiber, which are components of plant-based foods, such as legumes, whole grains and cereals, vegetables, fruits, and nuts or seeds. A diet high in regular fiber consumption is generally associated with supporting health and lowering the risk of several diseases. Dietary fiber consists of non-starch polysaccharides and other plant components such as cellulose, resistant starch, resistant dextrins, inulin, lignins, chitins, pectins, beta-glucans, and oligosaccharides.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by a group of symptoms that commonly include abdominal pain, abdominal bloating and changes in the consistency of bowel movements. These symptoms may occur over a long time, sometimes for years. IBS can negatively affect quality of life and may result in missed school or work or reduced productivity at work. Disorders such as anxiety, major depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome are common among people with IBS.

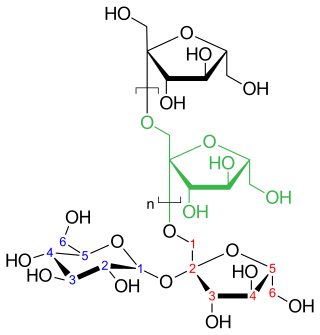

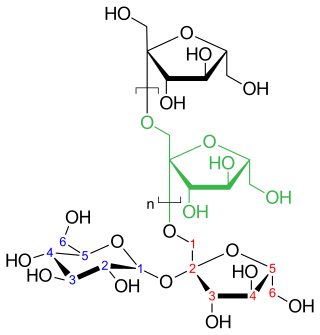

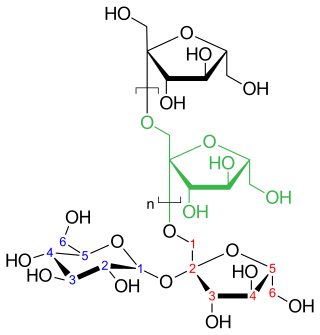

Inulins are a group of naturally occurring polysaccharides produced by many types of plants, industrially most often extracted from chicory. The inulins belong to a class of dietary fibers known as fructans. Inulin is used by some plants as a means of storing energy and is typically found in roots or rhizomes. Most plants that synthesize and store inulin do not store other forms of carbohydrate such as starch. In the United States in 2018, the Food and Drug Administration approved inulin as a dietary fiber ingredient used to improve the nutritional value of manufactured food products. Using inulin to measure kidney function is the "gold standard" for comparison with other means of estimating glomerular filtration rate.

A gluten-free diet (GFD) is a nutritional plan that strictly excludes gluten, which is a mixture of prolamin proteins found in wheat, as well as barley, rye, and oats. The inclusion of oats in a gluten-free diet remains controversial, and may depend on the oat cultivar and the frequent cross-contamination with other gluten-containing cereals.

Hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI) is an inborn error of fructose metabolism caused by a deficiency of the enzyme aldolase B. Individuals affected with HFI are asymptomatic until they ingest fructose, sucrose, or sorbitol. If fructose is ingested, the enzymatic block at aldolase B causes an accumulation of fructose-1-phosphate which, over time, results in the death of liver cells. This accumulation has downstream effects on gluconeogenesis and regeneration of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Symptoms of HFI include vomiting, convulsions, irritability, poor feeding as a baby, hypoglycemia, jaundice, hemorrhage, hepatomegaly, hyperuricemia and potentially kidney failure. While HFI is not clinically a devastating condition, there are reported deaths in infants and children as a result of the metabolic consequences of HFI. Death in HFI is always associated with problems in diagnosis.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID), also known as disorders of gut–brain interaction, include a number of separate idiopathic disorders which affect different parts of the gastrointestinal tract and involve visceral hypersensitivity and motility disturbances.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), also termed bacterial overgrowth, or small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome (SBBOS), is a disorder of excessive bacterial growth in the small intestine. Unlike the colon, which is rich with bacteria, the small bowel usually has fewer than 100,000 organisms per millilitre. Patients with bacterial overgrowth typically develop symptoms which may include nausea, bloating, vomiting, diarrhea, malnutrition, weight loss and malabsorption, which is caused by a number of mechanisms.

Prebiotics are compounds in food that foster growth or activity of beneficial microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi. The most common environment considered is the gastrointestinal tract, where prebiotics can alter the composition of organisms in the gut microbiome.

Food intolerance is a detrimental reaction, often delayed, to a food, beverage, food additive, or compound found in foods that produces symptoms in one or more body organs and systems, but generally refers to reactions other than food allergy. Food hypersensitivity is used to refer broadly to both food intolerances and food allergies.

Abdominal bloating is a short-term disease that affects the gastrointestinal tract. Bloating is generally characterized by an excess buildup of gas, air or fluids in the stomach. A person may have feelings of tightness, pressure or fullness in the stomach; it may or may not be accompanied by a visibly distended abdomen. Bloating can affect anyone of any age range and is usually self-diagnosed, in most cases does not require serious medical attention or treatment. Although this term is usually used interchangeably with abdominal distension, these symptoms probably have different pathophysiological processes, which are not fully understood.

A hydrogen breath test is used as a diagnostic tool for small intestine bacterial overgrowth and carbohydrate malabsorption, such as lactose, fructose, and sorbitol malabsorption.

A fructan is a polymer of fructose molecules. Fructans with a short chain length are known as fructooligosaccharides. Fructans can be found in over 12% of the angiosperms including both monocots and dicots such as agave, artichokes, asparagus, leeks, garlic, onions, yacón, jícama, barley and wheat.

Agave syrup, also known as maguey syrup or agave nectar, is a sweetener commercially produced from several species of agave, including Agave tequilana and Agave salmiana. Blue-agave syrup contains 56% fructose as a sugar providing sweetening properties.

Sucrose intolerance or genetic sucrase-isomaltase deficiency (GSID) is the condition in which sucrase-isomaltase, an enzyme needed for proper metabolism of sucrose (sugar) and starch, is not produced or the enzyme produced is either partially functional or non-functional in the small intestine. All GSID patients lack fully functional sucrase, while the isomaltase activity can vary from minimal functionality to almost normal activity. The presence of residual isomaltase activity may explain why some GSID patients are better able to tolerate starch in their diet than others with GSID.

Gluten-related disorders is the term for the diseases triggered by gluten, including celiac disease (CD), non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), gluten ataxia, dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) and wheat allergy. The umbrella category has also been referred to as gluten intolerance, though a multi-disciplinary physician-led study, based in part on the 2011 International Coeliac Disease Symposium, concluded that the use of this term should be avoided due to a lack of specificity.

FODMAPs or fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and ferment in the colon. They include short-chain oligosaccharide polymers of fructose (fructans) and galactooligosaccharides, disaccharides (lactose), monosaccharides (fructose), and sugar alcohols (polyols), such as sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, and maltitol. Most FODMAPs are naturally present in food and the human diet, but the polyols may be added artificially in commercially prepared foods and beverages.

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) or gluten sensitivity is a controversial disorder which can cause both gastrointestinal and other problems.

A low-FODMAP diet is a person's global restriction of consumption of all fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs), recommended only for a short time. A low-FODMAP diet is recommended for managing patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and can reduce digestive symptoms of IBS including bloating and flatulence.