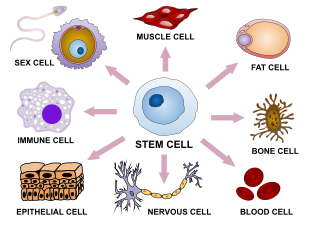

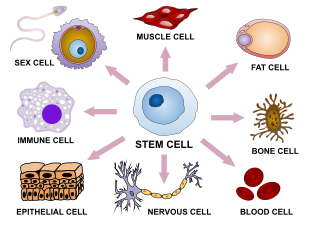

In multicellular organisms, stem cells are undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells that can change into various types of cells and proliferate indefinitely to produce more of the same stem cell. They are the earliest type of cell in a cell lineage. They are found in both embryonic and adult organisms, but they have slightly different properties in each. They are usually distinguished from progenitor cells, which cannot divide indefinitely, and precursor or blast cells, which are usually committed to differentiating into one cell type.

Transdifferentiation, also known as lineage reprogramming, is the process in which one mature somatic cell is transformed into another mature somatic cell without undergoing an intermediate pluripotent state or progenitor cell type. It is a type of metaplasia, which includes all cell fate switches, including the interconversion of stem cells. Current uses of transdifferentiation include disease modeling and drug discovery and in the future may include gene therapy and regenerative medicine. The term 'transdifferentiation' was originally coined by Selman and Kafatos in 1974 to describe a change in cell properties as cuticle producing cells became salt-secreting cells in silk moths undergoing metamorphosis.

Cellular differentiation is the process in which a stem cell changes from one type to a differentiated one. Usually, the cell changes to a more specialized type. Differentiation happens multiple times during the development of a multicellular organism as it changes from a simple zygote to a complex system of tissues and cell types. Differentiation continues in adulthood as adult stem cells divide and create fully differentiated daughter cells during tissue repair and during normal cell turnover. Some differentiation occurs in response to antigen exposure. Differentiation dramatically changes a cell's size, shape, membrane potential, metabolic activity, and responsiveness to signals. These changes are largely due to highly controlled modifications in gene expression and are the study of epigenetics. With a few exceptions, cellular differentiation almost never involves a change in the DNA sequence itself. However, metabolic composition does get altered quite dramatically where stem cells are characterized by abundant metabolites with highly unsaturated structures whose levels decrease upon differentiation. Thus, different cells can have very different physical characteristics despite having the same genome.

Homeobox protein NANOG(hNanog) is a transcriptional factor that helps embryonic stem cells (ESCs) maintain pluripotency by suppressing cell determination factors. hNanog is encoded in humans by the NANOG gene. Several types of cancer are associated with NANOG.

In biology, reprogramming refers to erasure and remodeling of epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation, during mammalian development or in cell culture. Such control is also often associated with alternative covalent modifications of histones.

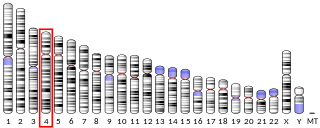

SOX genes encode a family of transcription factors that bind to the minor groove in DNA, and belong to a super-family of genes characterized by a homologous sequence called the HMG-box. This HMG box is a DNA binding domain that is highly conserved throughout eukaryotic species. Homologues have been identified in insects, nematodes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and a range of mammals. However, HMG boxes can be very diverse in nature, with only a few amino acids being conserved between species.

The inner cell mass (ICM) or embryoblast is a structure in the early development of an embryo. It is the mass of cells inside the blastocyst that will eventually give rise to the definitive structures of the fetus. The inner cell mass forms in the earliest stages of embryonic development, before implantation into the endometrium of the uterus. The ICM is entirely surrounded by the single layer of trophoblast cells of the trophectoderm.

Induced pluripotent stem cells are a type of pluripotent stem cell that can be generated directly from a somatic cell. The iPSC technology was pioneered by Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi in Kyoto, Japan, who together showed in 2006 that the introduction of four specific genes, collectively known as Yamanaka factors, encoding transcription factors could convert somatic cells into pluripotent stem cells. Shinya Yamanaka was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize along with Sir John Gurdon "for the discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become pluripotent."

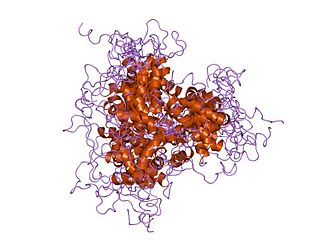

SRY -box 2, also known as SOX2, is a transcription factor that is essential for maintaining self-renewal, or pluripotency, of undifferentiated embryonic stem cells. Sox2 has a critical role in maintenance of embryonic and neural stem cells.

Shinya Yamanaka is a Japanese stem cell researcher and a Nobel Prize laureate. He is a professor and the director emeritus of Center for iPS Cell Research and Application, Kyoto University; as a senior investigator at the UCSF-affiliated Gladstone Institutes in San Francisco, California; and as a professor of anatomy at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Yamanaka is also a past president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR).

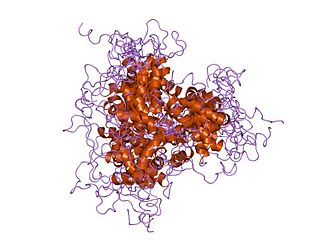

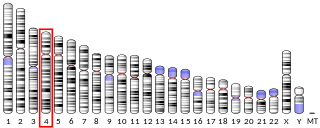

Sal-like protein 4(SALL4) is a transcription factor encoded by a member of the Spalt-like (SALL) gene family, SALL4. The SALL genes were identified based on their sequence homology to Spalt, which is a homeotic gene originally cloned in Drosophila melanogaster that is important for terminal trunk structure formation in embryogenesis and imaginal disc development in the larval stages. There are four human SALL proteins with structural homology and playing diverse roles in embryonic development, kidney function, and cancer. The SALL4 gene encodes at least three isoforms, termed A, B, and C, through alternative splicing, with the A and B forms being the most studied. SALL4 can alter gene expression changes through its interaction with many co-factors and epigenetic complexes. It is also known as a key embryonic stem cell (ESC) factor.

Rex1 (Zfp-42) is a known marker of pluripotency, and is usually found in undifferentiated embryonic stem cells. In addition to being a marker for pluripotency, its regulation is also critical in maintaining a pluripotent state. As the cells begin to differentiate, Rex1 is severely and abruptly downregulated.

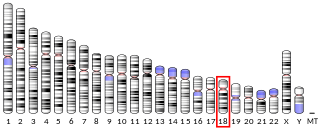

Forkhead box D3 also known as FOXD3 is a forkhead protein that in humans is encoded by the FOXD3 gene.

Cell potency is a cell's ability to differentiate into other cell types. The more cell types a cell can differentiate into, the greater its potency. Potency is also described as the gene activation potential within a cell, which like a continuum, begins with totipotency to designate a cell with the most differentiation potential, pluripotency, multipotency, oligopotency, and finally unipotency.

Embryonic stem cells are capable of self-renewing and differentiating to the desired fate depending on their position in the body. Stem cell homeostasis is maintained through epigenetic mechanisms that are highly dynamic in regulating the chromatin structure as well as specific gene transcription programs. Epigenetics has been used to refer to changes in gene expression, which are heritable through modifications not affecting the DNA sequence.

Undifferentiated embryonic cell transcription factor 1 is a protein in humans that is encoded by the UTF1 gene. UTF1, first reported in 1998, is expressed in pluripotent cells including embryonic stem cells and embryonic carcinoma cells. Its expression is rapidly reduced upon differentiation. UTF1 protein is localized to the cell nucleus, where it functions to regulate the pluripotent chromatin state and buffer mRNA levels by promoting degradation of mRNA.

Directed differentiation is a bioengineering methodology at the interface of stem cell biology, developmental biology and tissue engineering. It is essentially harnessing the potential of stem cells by constraining their differentiation in vitro toward a specific cell type or tissue of interest. Stem cells are by definition pluripotent, able to differentiate into several cell types such as neurons, cardiomyocytes, hepatocytes, etc. Efficient directed differentiation requires a detailed understanding of the lineage and cell fate decision, often provided by developmental biology.

After the blastocyst stage, once an embryo implanted in endometrium, the inner cell mass (ICM) of a fertilized embryo segregates into two layers: hypoblast and epiblast. The epiblast cells are the functional progenitors of soma and germ cells which later differentiate into three layers: definitive endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. Stem cells derived from epiblast are pluripotent. These cells are called epiblast-derived stem cells (EpiSCs) and have several different cellular and molecular characteristics with Embryonic Stem Cells (ESCs). Pluripotency in EpiSCs is essentially different from that of embryonic stem cells. The pluripotency of EpiSCs is primed pluripotency: primed to differentiate into specific cell lineages. Naïve pluripotent stem cells and primed pluripotent stem cells not only sustain the ability to self-renew but also maintain the capacity to differentiate. Since the cell status is primed to differentiate in EpiSCs, however, one copy of the X chromosome in XX cells in EpiSCs is silenced (XaXi). EpiSCs is unable to colonize and is not available to be used to produce chimeras. Conversely, XX cells in ESCs are both active and can produce chimera when inserted into a blastocyst. Both ESC and EpiSC induce teratoma when injected in the test animals which proves pluripotency. EpiSC display several distinctive characteristics distinct from ESCs. The cellular status of human ESCs (hESCs) is similar to primed state mouse stem cells rather than naïve state.

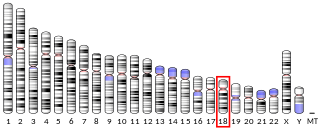

F-box protein 15 also known as Fbx15 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the FBXO15 gene.

David Suter is a Swiss physician and molecular and cell biologist. His research focuses on quantitative approaches to study gene expression and developmental cell fate decisions. He is currently a professor at EPFL, where he heads the Suter Lab at the Institute of Bioengineering of the School of Life Sciences.