Vegetable farming is the growing of vegetables for human consumption. The practice probably started in several parts of the world over ten thousand years ago, with families growing vegetables for their own consumption or to trade locally. At first manual labour was used but in time livestock were domesticated and the ground could be turned by the plough. More recently, mechanisation has revolutionised vegetable farming with nearly all processes being able to be performed by machine. Specialist producers grow the particular crops that do well in their locality. New methods—such as aquaponics, raised beds and cultivation under glass—are used. Marketing can be done locally in farmer's markets, traditional markets or pick-your-own operations, or farmers can contract their whole crops to wholesalers, canners or retailers.

Companion planting in gardening and agriculture is the planting of different crops in proximity for any of a number of different reasons, including weed suppression, pest control, pollination, providing habitat for beneficial insects, maximizing use of space, and to otherwise increase crop productivity. Companion planting is a form of polyculture.

Agriculture in Mesoamerica dates to the Archaic period of Mesoamerican chronology. At the beginning of the Archaic period, the Early Hunters of the late Pleistocene era led nomadic lifestyles, relying on hunting and gathering for sustenance. However, the nomadic lifestyle that dominated the late Pleistocene and the early Archaic slowly transitioned into a more sedentary lifestyle as the hunter gatherer micro-bands in the region began to cultivate wild plants. The cultivation of these plants provided security to the Mesoamericans, allowing them to increase surplus of "starvation foods" near seasonal camps; this surplus could be utilized when hunting was bad, during times of drought, and when resources were low. The cultivation of plants could have been started purposefully, or by accident. The former could have been done by bringing a wild plant closer to a camp site, or to a frequented area, so it was easier access and collect. The latter could have happened as certain plant seeds were eaten and not fully digested, causing these plants to grow wherever human habitation would take them.

Intercropping is a multiple cropping practice that involves the cultivation of two or more crops simultaneously on the same field, a form of polyculture. The most common goal of intercropping is to produce a greater yield on a given piece of land by making use of resources or ecological processes that would otherwise not be utilized by a single crop.

In agriculture, polyculture is the practice of growing more than one crop species together in the same place at the same time, in contrast to monoculture, which had become the dominant approach in developed countries by 1950. Traditional examples include the intercropping of the Three Sisters, namely maize, beans, and squashes, by indigenous peoples of Central and North America, the rice-fish systems of Asia, and the complex mixed cropping systems of Nigeria.

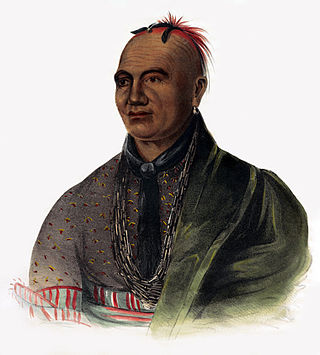

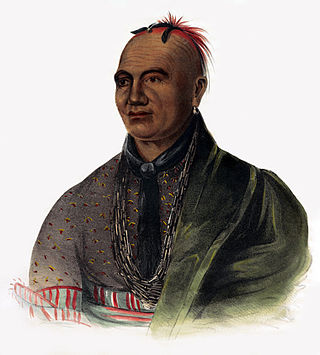

The Huron-Wendat Nation is an Iroquoian-speaking nation that was established in the 17th century. In the French language, used by most members of the First Nation, they are known as the Nation Huronne-Wendat. The French gave the nickname “Huron” to the Wendat, from the French word "hure" meaning “boar's head” because of the hairstyle of Huron men, who had their hair standing in bristles on their heads. Wendat (Quendat) was their confederacy name, meaning “people of the island” or "dwellers on a peninsula."

In agriculture, monocropping is the practice of growing a single crop year after year on the same land. Maize, soybeans, and wheat are three common crops often monocropped. Monocropping is also referred to as continuous cropping, as in "continuous corn." Monocropping allows for farmers to have consistent crops throughout their entire farm. They can plant only the most profitable crop, use the same seed, pest control, machinery, and growing method on their entire farm, which may increase overall farm profitability.

Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe, and included a diverse range of taxa. At least eleven separate regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent centers of origin. The development of agriculture about 12,000 years ago changed the way humans lived. They switched from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to permanent settlements and farming.

Domesticated plants of Mesoamerica, established by agricultural developments and practices over several thousand years of pre-Columbian history, include maize and capsicum. A list of Mesoamerican cultivars and staples:

Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands include Native American tribes and First Nation bands residing in or originating from a cultural area encompassing the northeastern and Midwest United States and southeastern Canada. It is part of a broader grouping known as the Eastern Woodlands. The Northeastern Woodlands is divided into three major areas: the Coastal, Saint Lawrence Lowlands, and Great Lakes-Riverine zones.

The Eastern Agricultural Complex in the woodlands of eastern North America was one of about 10 independent centers of plant domestication in the pre-historic world. Incipient agriculture dates back to about 5300 BCE. By about 1800 BCE the Native Americans of the woodlands were cultivating several species of food plants, thus beginning a transition from a hunter-gatherer economy to agriculture. After 200 BCE when maize from Mexico was introduced to the Eastern Woodlands, the Native Americans of the eastern United States and adjacent Canada slowly changed from growing local indigenous plants to a maize-based agricultural economy. The cultivation of local indigenous plants other than squash and sunflower declined and was eventually abandoned. The formerly domesticated plants returned to their wild forms.

Ancient Maya cuisine was varied and extensive. Many different types of resources were consumed, including maritime, flora, and faunal material, and food was obtained or produced through strategies such as hunting, foraging, and large-scale agricultural production. Plant domestication concentrated upon several core foods, the most important of which was maize.

Intensive crop farming is a modern industrialized form of crop farming. Intensive crop farming's methods include innovation in agricultural machinery, farming methods, genetic engineering technology, techniques for achieving economies of scale in production, the creation of new markets for consumption, patent protection of genetic information, and global trade. These methods are widespread in developed nations.

Maize, also known as corn in North American and Australian English, is a tall stout grass that produces cereal grain. It was domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago from wild teosinte. Native Americans planted it alongside beans and squashes in the Three Sisters polyculture. The leafy stalk of the plant gives rise to male inflorescences or tassels which produce pollen, and female inflorescences called ears which yield grain, known as kernels or seeds. In modern commercial varieties, these are usually yellow or white; other varieties can be of many colors.

A pumpkin, in English-language vernacular, is a cultivated winter squash in the genus Cucurbita. The term is most commonly applied to round, orange-colored squash varieties, though it does not possess a scientific definition and may be used in reference to many different squashes of varied appearance.

Chitemene, from the ciBemba word meaning “place where branches have been cut for a garden”, is a system of slash and burn agriculture practiced throughout northern Zambia. It involves coppicing or pollarding of standing trees in a primary or secondary growth Miombo woodland, stacking of the cut biomass, and eventual burning of the cut biomass in order to create a thicker layer of ash than would be possible with in situ burning. Crops such as maize, finger millet, sorghum, or cassava are then planted in the burned area.

Indigenous horticulture is practised in various ways across all inhabited continents. Indigenous refers to the native peoples of a given area and horticulture is the practice of small-scale intercropping.

Agriculture on the precontact Great Plains describes the agriculture of the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains of the United States and southern Canada in the Pre-Columbian era and before extensive contact with European explorers, which in most areas occurred by 1750. The principal crops grown by Indian farmers were maize (corn), beans, and squash, including pumpkins. Sunflowers, goosefoot, tobacco, gourds, and plums, were also grown.

Pre-Columbian cuisine refers to the cuisine consumed by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas before Christopher Columbus and other European explorers explored the region and introduced crops and livestock from Europe. Though the Columbian Exchange introduced many new animals and plants to the Americas, Indigenous civilizations already existed there, including the Aztec, Maya, Incan, as well as various Native Americans in North America. The development of agriculture allowed the many different cultures to transition from hunting to staying in one place. A major element of this cuisine is maize (corn), which began being grown in central Mexico. Other crops that flourished in the Americas include amaranth, wild rice, and lima beans.

Jane Mount Pleasant is an American agricultural scientist and associate professor emerita at Cornell University.