Brain abscess is an abscess within the brain tissue caused by inflammation and collection of infected material coming from local or remote infectious sources. The infection may also be introduced through a skull fracture following a head trauma or surgical procedures. Brain abscess is usually associated with congenital heart disease in young children. It may occur at any age but is most frequent in the third decade of life.

Cryptococcosis is a potentially fatal fungal infection of mainly the lungs, presenting as a pneumonia, and brain, where it appears as a meningitis. Cough, difficulty breathing, chest pain and fever are seen when the lungs are infected. When the brain is infected, symptoms include headache, fever, neck pain, nausea and vomiting, light sensitivity and confusion or changes in behavior. It can also affect other parts of the body including skin, where it may appear as several fluid-filled nodules with dead tissue.

Nocardiosis is an infectious disease affecting either the lungs or the whole body. It is due to infection by a bacterium of the genus Nocardia, most commonly Nocardia asteroides or Nocardia brasiliensis.

Fungal infection, also known as mycosis, is a disease caused by fungi. Different types are traditionally divided according to the part of the body affected; superficial, subcutaneous, and systemic. Superficial fungal infections include common tinea of the skin, such as tinea of the body, groin, hands, feet and beard, and yeast infections such as pityriasis versicolor. Subcutaneous types include eumycetoma and chromoblastomycosis, which generally affect tissues in and beneath the skin. Systemic fungal infections are more serious and include cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, pneumocystis pneumonia, aspergillosis and mucormycosis. Signs and symptoms range widely. There is usually a rash with superficial infection. Fungal infection within the skin or under the skin may present with a lump and skin changes. Pneumonia-like symptoms or meningitis may occur with a deeper or systemic infection.

Phycomycosis is an uncommon condition of the gastrointestinal tract and skin most commonly found in dogs and horses. The condition is caused by a variety of molds and fungi, and individual forms include pythiosis, zygomycosis, and lagenidiosis. Pythiosis is the most common type and is caused by Pythium, a type of water mould. Zygomycosis can also be caused by two types of zygomycetes, Entomophthorales and Mucorales. The latter type of zygomycosis is also referred to as mucormycosis. Lagenidiosis is caused by a Lagenidium species, which like Pythium is a water mould. Since both pythiosis and lagenidiosis are caused by organisms from the Oomycetes and not the kingdom fungi, they are sometimes collectively referred to as oomycosis.

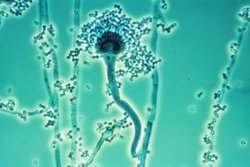

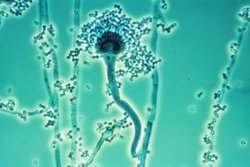

Aspergillosis is a fungal infection of usually the lungs, caused by the genus Aspergillus, a common mould that is breathed in frequently from the air, but does not usually affect most people. It generally occurs in people with lung diseases such as asthma, cystic fibrosis or tuberculosis, or COVID-19 or those who are immunocompromized such as those who have had a stem cell or organ transplant or those who take medications such as steroids and some cancer treatments which suppress the immune system. Rarely, it can affect skin.

Apophysomyces is a genus of filamentous fungi that are commonly found in soil and decaying vegetation. Species normally grow in tropical to subtropical regions.

Conidiobolomycosis is a rare long-term fungal infection that is typically found just under the skin of the nose, sinuses, cheeks and upper lips. It may present with a nose bleed or a blocked or runny nose. Typically there is a firm painless swelling which can slowly extend to the nasal bridge and eyes, sometimes causing facial disfigurement.

Mucormycosis, also known as black fungus, is a serious fungal infection that comes under fulminant fungal sinusitis, usually in people who are immunocompromised. It is curable only when diagnosed early. Symptoms depend on where in the body the infection occurs. It most commonly infects the nose, sinuses, eyes and brain resulting in a runny nose, one-sided facial swelling and pain, headache, fever, blurred vision, bulging or displacement of the eye (proptosis), and tissue death. Other forms of disease may infect the lungs, stomach and intestines, and skin. The fatality rate is about 54%.

Saksenaea vasiformis is an infectious fungus associated with cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions following trauma. It causes opportunistic infections as the entry of the fungus is through open spaces of cutaneous barrier ranging in severity from mild to severe or fatal. It lives in soils worldwide, but is considered as a rare human pathogen since only 38 cases were reported as of 2012. Saksenaea vasiformis usually fails to sporulate on the routine culture media, creating a challenge for early diagnosis, which is essential for a good prognosis. Infections are usually treated using a combination of amphotericin B and surgery. Saksenaea vasiformis is one of the few fungi known to cause necrotizing fasciitis or "flesh-eating disease".

Entomophthoramycosis is a mycosis caused by Entomophthorales.

Rhizomucor pusillus is a species of Rhizomucor. It can cause disease in humans. R. pusillus is a grey mycelium fungi most commonly found in compost piles. Yellow-brown spores grow on a stalk to reproduce more fungal cells.

Apophysomyces variabilis is an emerging fungal pathogen that can cause serious and sometimes fatal infection in humans. This fungus is a soil-dwelling saprobe with tropical to subtropical distribution. It is a zygomycete that causes mucormycosis, an infection in humans brought about by fungi in the order Mucorales. Infectious cases have been reported globally in locations including the Americas, Southeast Asia, India, and Australia. Apophysomyces variabilis infections are not transmissible from person to person.

Lichtheimia corymbifera is a thermophilic fungus in the phylum Zygomycota. It normally lives as a saprotrophic mold, but can also be an opportunistic pathogen known to cause pulmonary, CNS, rhinocerebral, or cutaneous infections in animals and humans with impaired immunity.

Cunninghamella bertholletiae is a species of zygomycetous fungi in the order Mucorales. It is found globally, with increased prevalence in Mediterranean and subtropical climates. It typically grows as a saprotroph and is found in a wide variety of substrates, including soil, fruits, vegetables, nuts, crops, and human and animal waste. Although infections are still rare, C. betholletiae is emerging as an opportunistic human pathogen, predominantly in immunocompromised people, leukemia patients, and people with uncontrolled diabetes. Cunninghamella bertholletiae infections are often highly invasive, and can be more difficult to treat with antifungal drugs than infections with other species of the Mucorales, making prompt and accurate recognition and diagnosis of mycoses caused by this fungus an important medical concern.

Fungal sinusitis or fungal rhinosinusitis is the inflammation of the lining mucosa of the paranasal sinuses due to a fungal infection. It occurs in people with reduced immunity. The maxillary sinus is the most commonly involved. Fungi responsible for fungal sinusitis are Aspergillus fumigatus (90%), Aspergillus flavus, and Aspergillus niger. Fungal sinusitis occurs most commonly in middle-aged populations. Diabetes mellitus is the most common risk factor involved.

Rhizopus oryzae is a filamentous heterothallic microfungus that occurs as a saprotroph in soil, dung, and rotting vegetation. This species is very similar to Rhizopus stolonifer, but it can be distinguished by its smaller sporangia and air-dispersed sporangiospores. It differs from R. oligosporus and R. microsporus by its larger columellae and sporangiospores. The many strains of R. oryzae produce a wide range of enzymes such as carbohydrate digesting enzymes and polymers along with a number of organic acids, ethanol and esters giving it useful properties within the food industries, bio-diesel production, and pharmaceutical industries. It is also an opportunistic pathogen of humans causing mucormycosis.

Microascus manginii is a filamentous fungal species in the genus Microascus. It produces both sexual (teleomorph) and asexual (anamorph) reproductive stages known as M. manginii and Scopulariopsis candida, respectively. Several synonyms appear in the literature because of taxonomic revisions and re-isolation of the species by different researchers. M. manginii is saprotrophic and commonly inhabits soil, indoor environments and decaying plant material. It is distinguishable from closely related species by its light colored and heart-shaped ascospores used for sexual reproduction. Scopulariopsis candida has been identified as the cause of some invasive infections, often in immunocompromised hosts, but is not considered a common human pathogen. There is concern about amphotericin B resistance in S. candida.

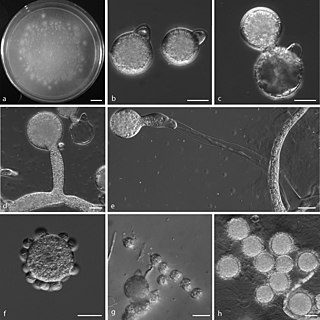

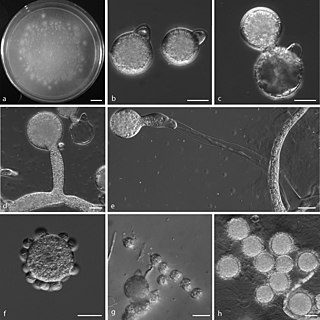

Mycotypha microspora, also known as Microtypha microspora, is a filamentous fungus in the division Zygomycota. It was discovered in a Citrus aurantium peel in 1932 by E. Aline Fenner, who proposed a new genus Mycotypha to accommodate it. Mycotypha africana, which is another species in the genus Mycotypha, is closely related to M. microspora. The fungus has subsequently been isolated from both outdoor and indoor settings around the world, and is typically found in soil and dung. The species rarely causes infections in humans, but has recently been involved in the clinical manifestation of the life-threatening disease mucormycosis.

Lichtheimia ramosa is a saprotrophic zygomycete, typically found in soil or dead plant material. It is a thermotolerant fungus that has also been known to act as an opportunistic pathogen–infecting both humans and animals.