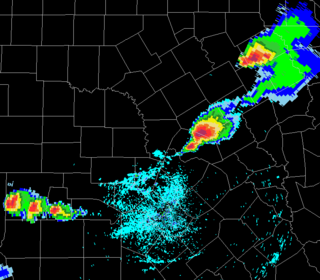

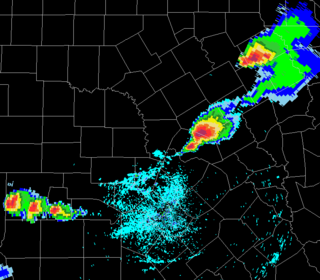

A deadly tornado outbreak occurred in Central Texas during the afternoon and evening of May 27, 1997, in conjunction with a southwestward-moving cluster of supercell thunderstorms. These storms produced 20 tornadoes, mainly along the Interstate 35 corridor from northeast of Waco to north of San Antonio. The strongest tornado was an F5 tornado that leveled parts of Jarrell, killing 27 people and injuring 12 others. Overall, 30 people were killed and 33 others were hospitalized by the severe weather.

Tetsuya Theodore Fujita was a Japanese and American meteorologist whose research primarily focused on severe weather. His research at the University of Chicago on severe thunderstorms, tornadoes, hurricanes, and typhoons revolutionized the knowledge of each. Although he is best known for creating the Fujita scale of tornado intensity and damage, he also discovered downbursts and microbursts and was an instrumental figure in advancing modern understanding of many severe weather phenomena and how they affect people and communities, especially through his work exploring the relationship between wind speed and damage.

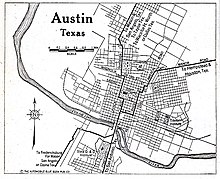

A deadly series of at least 33 tornadoes hit at least 10 different U.S. states on May 9–11, 1953. Tornadoes appeared daily from Minnesota in the north to Texas in the south. The strongest and deadliest tornado was a powerful F5 tornado that struck Waco, Texas on May 11, causing 114 of the 144 deaths in the outbreak. Alongside the 1902 Goliad tornado, it was the deadliest tornado in Texas history and is the 11th deadliest tornado in U.S. history. The tornado's winds demolished more than 600 houses, 1,000 other structures, and over 2,000 vehicles. 597 injuries occurred, and many survivors had to wait more than 14 hours for rescue. The destruction dispelled a myth that the geography of the region spared Waco from tornadoes, and along with other deadly tornadoes in 1953, the Waco disaster was a catalyst for advances in understanding the link between tornadoes and radar-detected hook echoes. It also generated support for improved civil defense systems, the formation of weather radar networks, and improved communications between stakeholders such as meteorologists, local officials, and the public.

Portions of Lubbock, Texas, were struck by a powerful multiple-vortex tornado after nightfall on May 11, 1970, resulting in 26 fatalities and an estimated $250 million in damage. It was in its time the costliest tornado in U.S. history, damaging nearly 9,000 homes and inflicting widespread damage to businesses, high-rise buildings, and public infrastructure. The tornado's damage was surveyed by meteorologist Ted Fujita in what researcher Thomas P. Grazulis described as "the most detailed mapping ever done, up to that time, of the path of a single tornado." Originally, the most severe damage was assigned a preliminary F6 rating on the Fujita scale, making it one of only two tornadoes to receive the rating, alongside the 1974 Xenia tornado. Later, it was downgraded to an F5 rating. The extremity of the damage and the force required to displace heavy objects as much as was observed indicated that winds produced by vortices within the tornado may have exceeded 290 mph (470 km/h).

On Tuesday, April 10, 1979, a widespread and destructive outbreak of severe weather impacted areas near the Red River between Oklahoma and Texas. Thunderstorms developed over West and North Central Texas during the day within highly unstable atmospheric conditions following the northward surge of warm and moist air into the region, producing large hail, strong winds, and multiple tornadoes. At least 22 tornadoes were documented on April 10, of which two were assigned an F4 rating on the Fujita scale; four of the tornadoes caused fatalities.

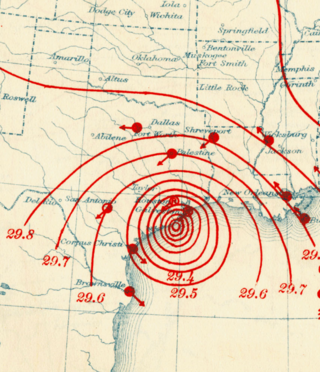

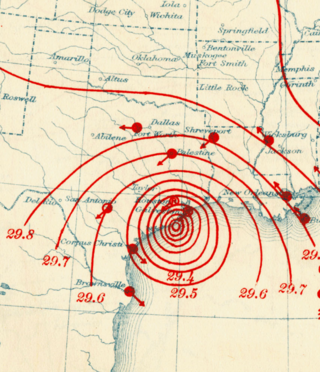

Hurricane Audrey was one of the deadliest hurricanes in U.S. history, killing at least 416 people as it devastated the southwestern Louisiana coast in 1957. Along with Hurricane Alex in 2010, it was also the strongest June hurricane ever recorded in the Atlantic basin as measured by pressure. The rapidly developing storm struck southwestern Louisiana as an intense Category 3 hurricane, destroying coastal communities with a powerful storm surge that penetrated as far as 20 mi (32 km) inland. The first named storm and hurricane of the 1957 hurricane season, Audrey formed on June 24 from a tropical wave that moved into the Bay of Campeche. Situated within ideal conditions for tropical development, Audrey quickly strengthened, reaching hurricane status a day afterwards. Moving north, it continued to strengthen and accelerate as it approached the United States Gulf Coast. On June 27, the hurricane reached peak sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h), making it a major hurricane. At the time, Audrey had a minimum barometric pressure of 946 mbar. The hurricane made landfall with the same intensity between the mouth of the Sabine River and Cameron, Louisiana, later that day, causing unprecedented destruction across the region. Once inland, Audrey weakened and turned extratropical over West Virginia on June 29. Audrey was the first major hurricane to form in the Gulf of Mexico since 1945.

The 1915 Galveston hurricane was a tropical cyclone that caused extensive damage in the Galveston area in August 1915. Widespread damage was also documented throughout its path across the Caribbean Sea and the interior of the United States. Due to similarities in strength and trajectory, the storm drew comparisons with the deadly 1900 Galveston hurricane. While the newly completed Galveston Seawall mitigated a similar-scale disaster for Galveston, numerous fatalities occurred along unprotected stretches of the Texas coast due to the storm's 16.2 ft (4.9 m) storm surge. Overall, the major hurricane inflicted at least $30 million in damage and killed 403–405 people. A demographic normalization of landfalling storms suggested that an equivalent storm in 2005 would cause $68.0 billion in damage in the United States.

The 1916 Texas hurricane was an intense and quick-moving tropical cyclone that caused widespread damage in Jamaica and South Texas in August 1916. A Category 4 hurricane upon landfall in Texas, it was the strongest tropical cyclone to strike the United States in three decades. Throughout its eight-day trek across the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, the hurricane caused 37 fatalities and inflicted $11.8 million in damage.

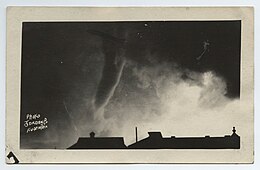

On April 2–5, 1957, a deadly tornado outbreak sequence struck most of the Southern United States. The outbreak killed at least 21 people across three states and produced at least 73 tornadoes from Texas to Virginia. The outbreak was most notable due to a tornado that hit a densely populated area of the Dallas–Fort Worth metropolitan area, killing 10 people and injuring 200 or more. The tornado, highly visible for most of its path, was at the time the most observed and best-documented tornado in recorded history; hundreds of people photographed or filmed the F3 tornado as it moved just west of Downtown Dallas. The film of this tornado is still known for its unusually high quality and sharpness, considering the photography techniques and technology of the 1950s. Damage from the Dallas tornado reached as high as $4 million. Besides the famous Dallas tornado, other deadly tornadoes struck portions of Mississippi, Texas, and Oklahoma. Two F4 tornadoes struck southern Oklahoma on April 2, killing five people. Three other significant, F2-rated tornadoes that day killed two people in Texas and one more in Oklahoma. An F3 tornado struck rural Mississippi on April 4, killing one more person.

From May 3 to May 11, 2003, a prolonged and destructive series of tornado outbreaks affected much of the Great Plains and Eastern United States. Most of the severe activity was concentrated between May 4 and May 10, which saw more tornadoes than any other week-long span in recorded history; 335 tornadoes occurred during this period, concentrated in the Ozarks and central Mississippi River Valley. Additional tornadoes were produced by the same storm systems from May 3 to May 11, producing 363 tornadoes overall, of which 62 were significant. Six of the tornadoes were rated F4, and of these four occurred on May 4, the most prolific day of the tornado outbreak sequence; these were the outbreak's strongest tornadoes. Damage caused by the severe weather and associated flooding amounted to US$4.1 billion, making it the costliest U.S. tornado outbreak of the 2000s. A total of 50 deaths and 713 injuries were caused by the severe weather, with a majority caused by tornadoes; the deadliest tornado was an F4 that struck Madison and Henderson counties in Tennessee, killing 11. In 2023, tornado expert Thomas P. Grazulis created the outbreak intensity score (OIS) as a way to rank various tornado outbreaks. The tornado outbreak sequence of May 2003 received an OIS of 232, making it the fourth worst tornado outbreak in recorded history.

This page documents the tornadoes and tornado outbreaks of 1962, primarily in the United States. Most tornadoes form in the U.S., although tornadoes events can take place internationally. Tornado statistics for older years like this often appear significantly lower than modern years due to fewer reports or confirmed tornadoes.

This page documents notable tornadoes and tornado outbreaks worldwide in 2019. Strong and destructive tornadoes form most frequently in the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Bangladesh, and Eastern India, but can occur almost anywhere under the right conditions. Tornadoes also develop occasionally in southern Canada during the Northern Hemisphere's summer and somewhat regularly at other times of the year across Europe, Asia, Argentina, and Australia. Tornadic events are often accompanied by other forms of severe weather, including strong thunderstorms, strong winds, and hail.

The 1944 Jamaica hurricane was a deadly major hurricane that swept across the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico in August 1944. Conservative estimates placed the storm's death toll at 116. The storm was already well-developed when it was first noted passing westward over the Windward Islands into the Caribbean Sea on August 16. A ship near Grenada with 74 occupants was lost, constituting a majority of the deaths associated with the storm. The following day, the storm intensified into a hurricane, reaching its peak strength on August 20 with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). At this intensity, the major hurricane made landfall on Jamaica later that day, traversing the length of the island. The damage wrought was extensive, with the strong winds destroying 90 percent of banana trees and 41 percent of coconut trees in Jamaica; the overall damage toll was estimated at "several millions of dollars". The northern coast of Jamaica saw the most severe damage, with widespread structural damage and numerous homes destroyed across several parishes. In Port Maria, the storm was considered the worst since 1903.

A widespread, destructive, and deadly tornado outbreak sequence affected the Southeastern United States from April 28 to May 2, 1953, producing 24 tornadoes, including five violent F4 tornadoes. The deadliest event of the sequence was an F4 tornado family that ravaged Robins Air Force Base in Warner Robins, Georgia, on April 30, killing at least 18 people and injuring 300 or more others. On May 1, a pair of F4 tornadoes also struck Alabama, causing a combined nine deaths and 15 injuries. Additionally, another violent tornado struck rural Tennessee after midnight on May 2, killing four people and injuring eight. Additionally, two intense tornadoes impacted Greater San Antonio, Texas, on April 28, killing three people and injuring 20 altogether. In all, 36 people were killed, 361 others were injured, and total damages reached $26.713 million (1953 USD). There were additional casualties from non-tornadic events as well, including a washout which caused a train derailment that injured 10.

A small but damaging outbreak of 11 tornadoes impacted the Southeastern United States on the last two days of March 1962. The outbreak was highlighted by a catastrophic, mid-morning F3 tornado that destroyed multiple neighborhoods in Milton, Florida, killing 17 people and injuring 100 others. It was the deadliest tornado ever recorded in Florida until 1998. Overall, the outbreak killed 17 people, injured 105 others, and caused $3.38 million in damage. Lightning caused another two deaths and three injuries.

This page documents notable tornadoes and tornado outbreaks worldwide in 2021. Strong and destructive tornadoes form most frequently in the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Bangladesh, and Eastern India, but can occur almost anywhere under the right conditions. Tornadoes also develop occasionally in southern Canada during the Northern Hemisphere's summer and somewhat regularly at other times of the year across Europe, Asia, Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. Tornadic events are often accompanied by other forms of severe weather, including strong thunderstorms, strong winds, and hail. Worldwide, 150 tornado-related deaths were confirmed with 103 in the United States, 28 in China, six in the Czech Republic, four in Russia, three in Italy, two in India, and one each in Canada, New Zealand, Indonesia, and Turkey.

The February 13–17, 2021 North American winter storm was a crippling winter and ice storm that had widespread impacts across the United States, Northern Mexico, and parts of Canada from February 13 to 17, 2021. The storm, unofficially referred to as Winter Storm Uri by the Weather Channel, started out in the Pacific Northwest and quickly moved into the Southern United States, before moving on to the Midwestern and Northeastern United States a couple of days later.

On May 27, 1997, a large and slow-moving F5 tornado caused catastrophic damage across portions of the Jarrell, Texas area. The tornado killed 27 residents of the town, mainly in a single subdivision, and inflicted approximately $40 million in damages in its 13-minute, 5.1 miles (8.2 km) track. It occurred as part of a tornado outbreak across central Texas; it was produced by a supercell that had developed from an unstable airmass and favorable meteorological conditions at the time, including high convective available potential energy (CAPE) values and warm dewpoints.

This page documents notable tornadoes and tornado outbreaks worldwide in 2022. Strong and destructive tornadoes form most frequently in the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Bangladesh, and Eastern India, but can occur almost anywhere under the right conditions. Tornadoes also develop occasionally in southern Canada during the Northern Hemisphere's summer and somewhat regularly at other times of the year across Europe, Asia, Argentina, Australia and New Zealand. Tornadic events are often accompanied by other forms of severe weather, including strong thunderstorms, strong winds, and hail. Worldwide, 32 tornado-related deaths were confirmed: 23 in the United States, three in China, two each in Poland and Russia, and one each in the Netherlands and Ukraine.

This page documents the tornadoes and tornado outbreaks of 1946, primarily in the United States. Most recorded tornadoes form in the U.S., although some events may take place internationally. Tornado statistics for older years like this often appear significantly lower than modern years due to fewer reports or confirmed tornadoes.